This article is the first part of a six-part series detailing youth political subcultures and the role of youth political participation and activism in the past and present. By highlighting political activity at DU, this column seeks to find patterns in historical and present-day activism among youth populations. It hopes to shed light on how American youth populations view various political issues in different or similar ways from other youth voters and older generations.

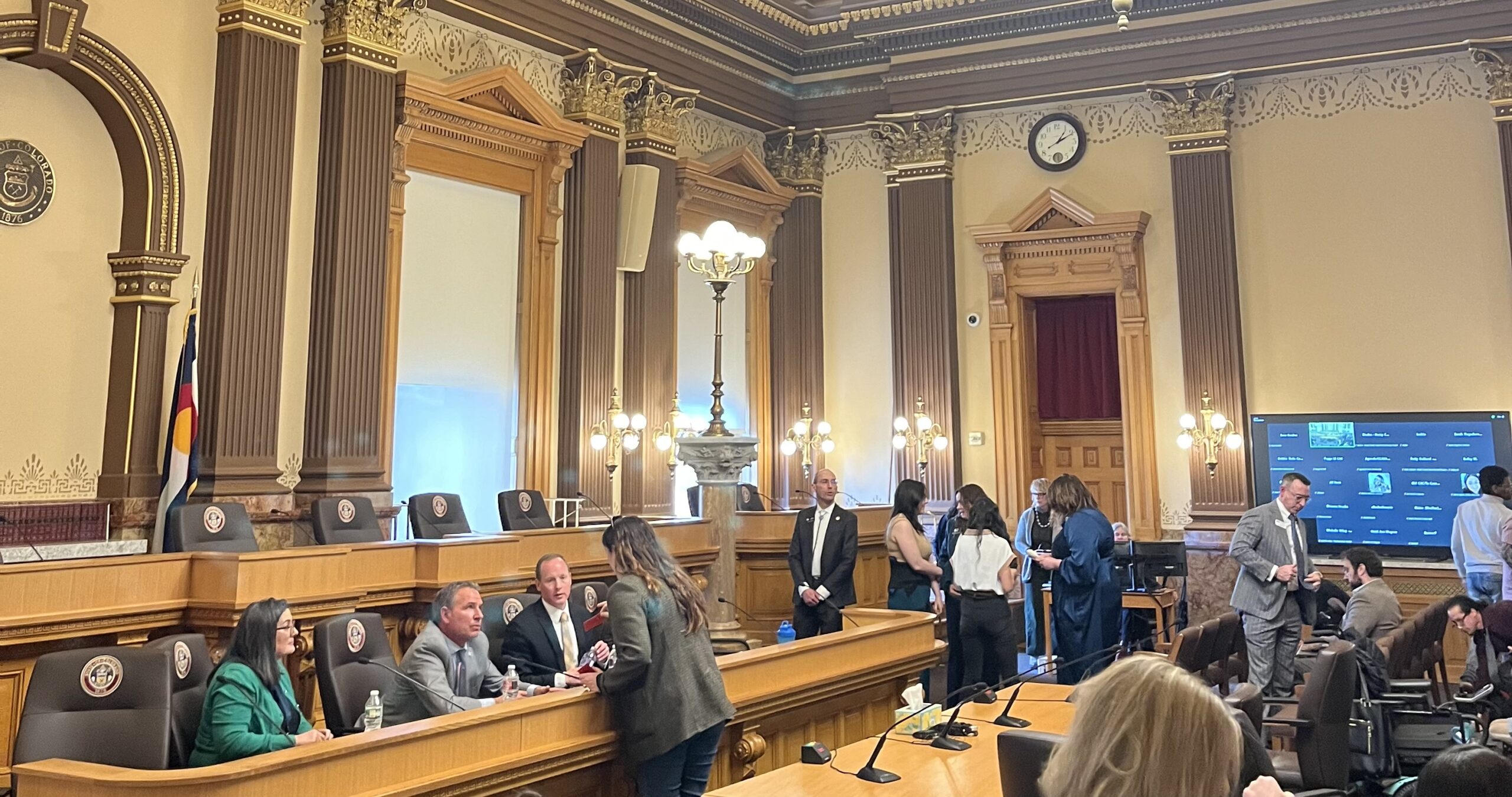

A parade of sign-bearing protestors dressed in red is not something many college campuses see on a typical Friday afternoon. Yet, on Sept. 25, hundreds of DU students supporting Righteous Anger! Healing Resistance! (R.A.H.R.), an unofficial student group, marched from Mary Reed green to the university’s surrounding streets.

Accompanied by lively chants and confused passersby, student protestors demanded seven actions from DU administration: removing DU’s “Pioneer” mascot, creating a critical race and ethnic studies department, reconstituting the Native American Advisory Board, hiring and retaining more faculty of color, increasing engagement with indigenous communities, divesting from all ties with ICE and creating a student seat on the Board of Trustees.

In this fervent political expression, DU students echoed a trend becoming more accepted since 2016: young people do care about politics. Since 2004, youth voter turnout has remained above 40%. 2018’s midterm election saw the biggest in more than 25 years. That year, youth voters proved themselves politically active through signing petitions, attending protests and/or marches and publicly supporting a candidate.

There is no doubt that American youth are a powerful force. While age—like other identifying factors of race, gender, class, sexuality and more—is not a ubiquitous determinant of political beliefs, it does bind a generation by shared values and experiences.

In their 2018 book, “The Politics of Millennials,” authors Stella Rouse and Ashley Ross explain the difference in millennials and older adults, writing that millennials “prefer to engage in political problems directly, see issues from a cosmopolitan (or global) viewpoint and seek to affirm principles of social justice and tolerance.” Just like the generations that precede and follow them, millennials possess generational characteristics that largely define their age group.

However, Rouse and Ross also claim that “millennials are far from the monolithic group portrayed by pundits and the news media.” In fact, anyone who has seen an episode of Parks and Recreation can tell you that elections and politics in general are complicated. There are men’s rights groups, wealthy corporation owners, family stability organizations and the Swansons and Knopes of the world who clash on basic governmental principles.

To top it off, America’s teenagers and 20-somethings are almost all members of Generation Z, which may just be the most complicated and diverse political generation ever. A study from the Pew Research Center reported that, like millennials, Gen Z curbs away from older generational politics: “Gen Zers are progressive and pro-government, most see the country’s growing racial and ethnic diversity as a good thing, and they’re less likely than older generations to see the United States as superior to other nations.”

According to experts like Seth Masket, a professor of political science and director of DU’s Center on American Politics, young voters are also less party-happy than older generations.

“I think younger voters today are much less likely to call themselves part of a political party than older voters are or were,” said Seth Masket of the youth’s political diversity. Masket is a professor of political science and director of DU’s Center on American Politics. “I don’t know if that’s going to change as they [young people] get older. Even if they are voting regularly for one party, they still prefer to call themselves independent, undecided or uncommitted. To some extent, that changes how a party behaves.”

The purpose of this column, “The Young and Restless,” is to analyze the weird political subcultures of TikTok-ing, college-going, studio-apartment-living, protest-attending youth—from young Black conservatives to Bernie bros. It will feature exclusive Clarion interviews with political groups, professors and general humans from the DU and Denver area.

Through research and interviews, I strive to analyze the independent, undecided and uncommitted factions within larger factions and how young Americans identify with far more individualized subcultures and political posses than those represented in our two-party system. The United States is beyond elephants and donkeys; we identify as the whole zoo.

Youth voter participation: A dismal reputation

Young people are a historically powerful voice in American politics. More than a dozen of America’s founding fathers were younger than 35, such as instrumental figures like Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay and James Madison. Young people have also played integral roles in American activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the 1970 Women’s Strike for Equality. Former DU student and the first Black Secretary of State, Condoleeza Rice, was the youngest national security adviser in history and the youngest provost of Stanford University as well.

Yet, over the course of American history, youth political participation has ebbed and flowed. Young voters in the 19th century dedicated their social scenes and free time to party politics, voting and debating. However, while “80 percent of eligible voters had turned out” in the 1896 election of William McKinley, less than half of youth voters were showing up to the polls “by the 1920s.”

This trend continued throughout the 1900s, cementing a stereotype of a laissez-faire youth more interested in pop culture and school than politics. In fact, youth voters aged 18-24 have maintained the lowest overall turnout in U.S. general elections out of all age groups since 1964.

However, after a century of inferior political performance, a recent rise in youth movements indicate a potential shift not only in voter turnout but in overall youth political mobilization. This is easily noticeable in Sunrise Movement’s climate activism, high school student-led school walkouts protesting gun violence and the high youth involvement in 2020’s Black Lives Matter protests.

“Nationally, we’ve seen the BLM movement take over the nation, so we’re trying to bring that back to our campus and set it in our context,” said fourth-year Maya Bhowmik, one of the student organizers of DU’s Friday R.A.H.R. protest. “We thought the best way to do that was to re-address demands that have gone unaddressed from the past, so we are re-demanding things that have not been addressed by the administration.”

“Woodstock West” and DU’s activist history

Bhowmik is correct in saying these demands stretch to the past—and they stretch back quite far, in fact.

In an interview with The Clarion, DU film professor Sheila Schroeder shared her expertise on “Woodstock West,” perhaps the largest political demonstration to ever occur on DU’s campus. She spoke on how students at DU have been demanding an ethnic and critical race department and more faculty of color since the 1960s.

“On campus, the students were focused on some of the Black student issues like getting an ethnic or Black studies department,” said Schroeder. “Sound familiar? That’s exactly what’s going on now.”

Aside from Friday’s protest, DU student-based Instagram accounts like RememberX and wecandubetter also rally for changes in DU’s political agenda. While RememberX calls attention to DU’s political history and wecandubetter posts anonymous stories of gender-based violence on campus, political activism continues on campus today.

Outside of DU, other college campus protests have made hot-topic headlines in the cases of Ohio University’s 2018 sexual assault protests, Georgetown University’s 2014 Keystone Pipline protest, Florida State University’s simultaneous anti-abortion and pro-choice demonstrations in 2018 and countless others.

A call to action in 2020

While many young people noticeably care about socio-political issues, both Democrats and Republicans are pushing their young constituents to actually fill out ballots.

After the 2016 election, the faculty advisors of DU Republicans (Andrew Sherbo) and DU Democrats (Stever Fisher) both wrote op-eds to the Clarion that stressed the need for students to vote and politically educate themselves.

“Still, people will complain our elected officials don’t represent us as citizens,” wrote Sherbo. “I am not surprised. We can only really ‘Make America Great Again’ (Trump) or be ‘Stronger Together’ (Clinton) when we exercise our civic duty to simply vote. It is not that difficult to do once every two and four years. We are not that busy.”

In his short and less emotional response, Fisher wrote about young Democrats’ disappointment with Trump’s electoral college win in 2016.

“I believe the Trump victory was made a bit more difficult because Clinton led in the polls and won the popular vote despite losing the electoral college vote,” wrote Fisher. “Many younger Democrats may not be as familiar with the electoral college.”

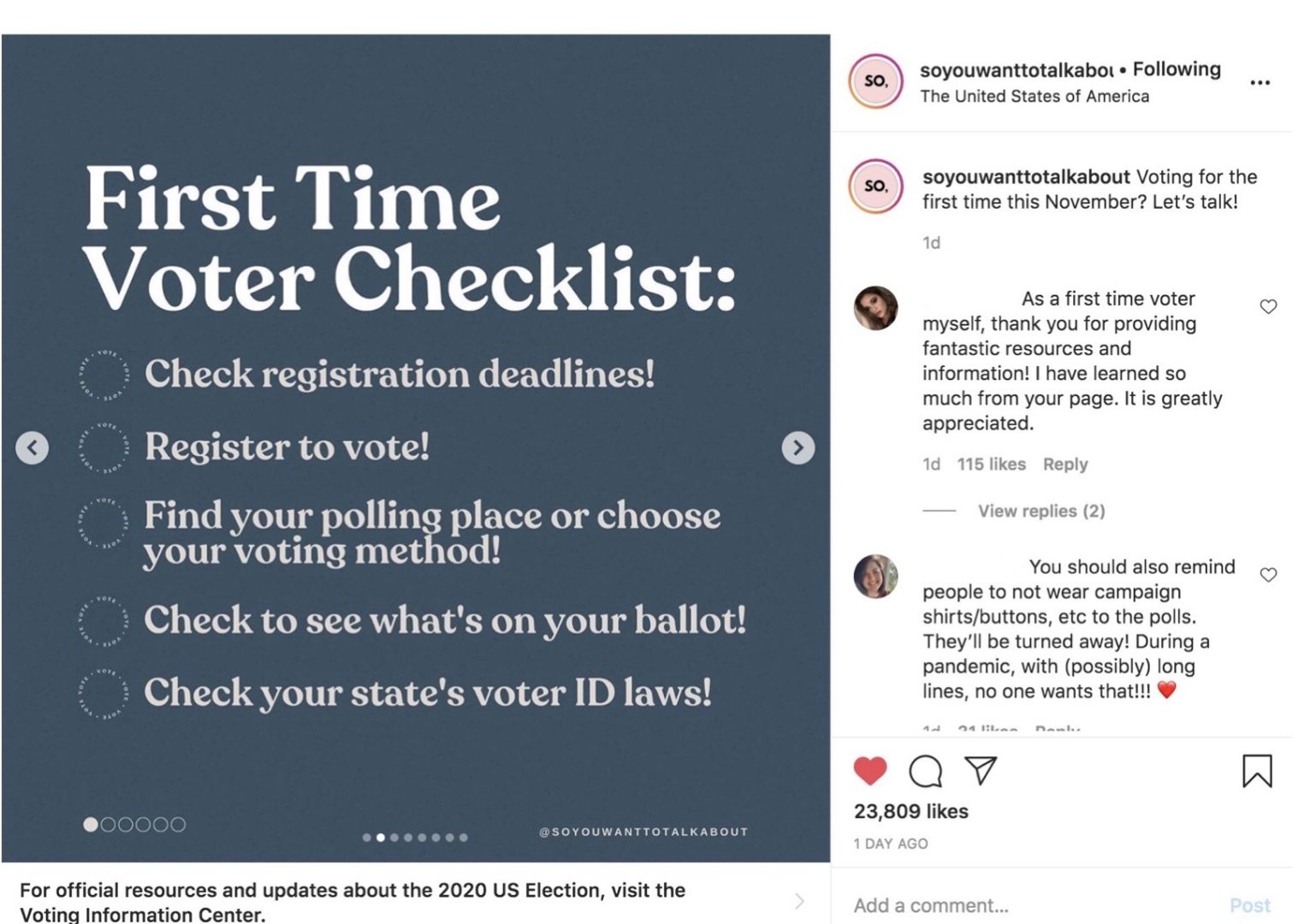

More recently, and since the Black Lives Matter protests this summer, Americans plaster pleas for young people to vote all over social media. Popular youth social media apps like TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat now immediately post voter registration links upon opening the platforms.

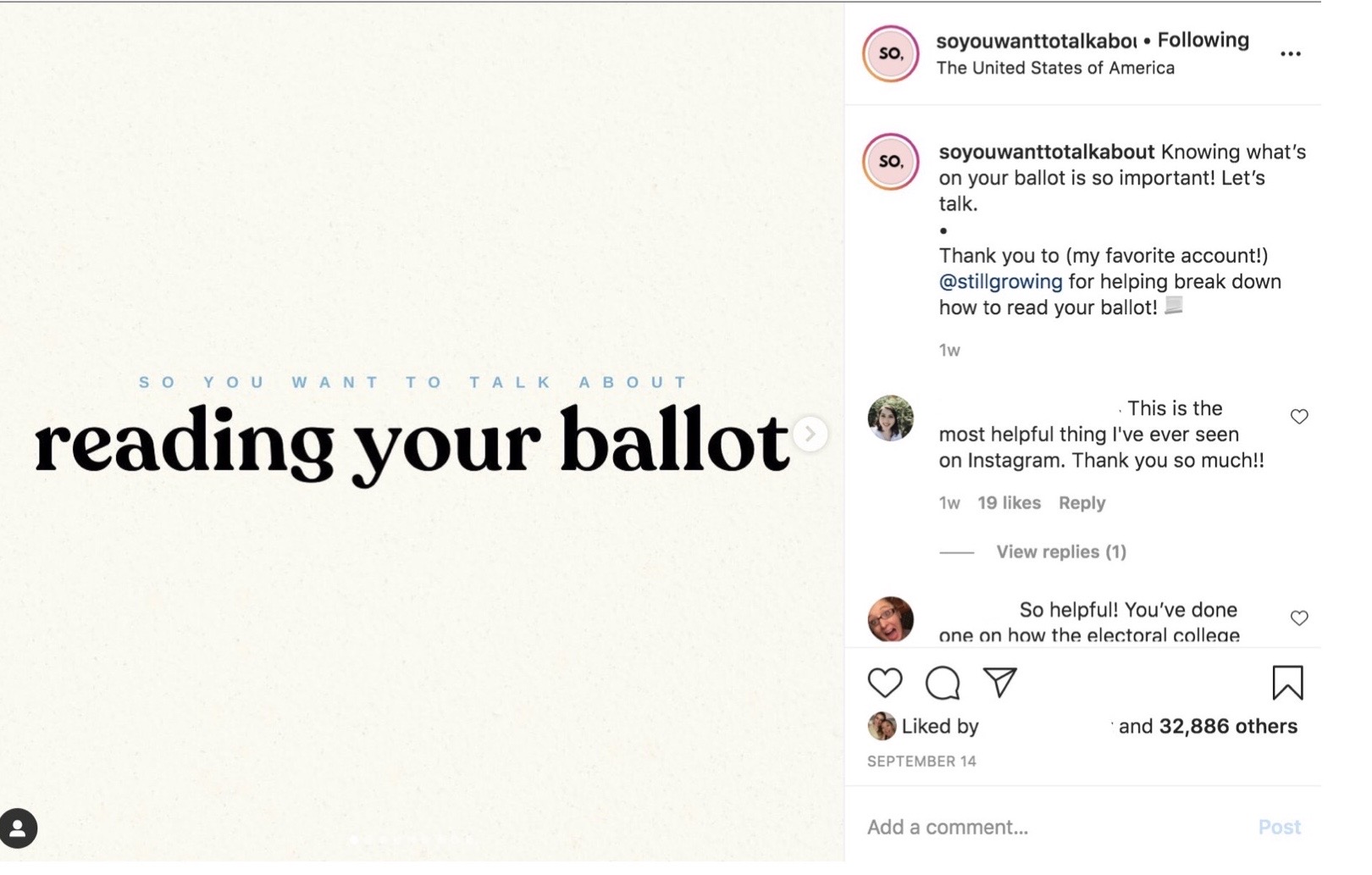

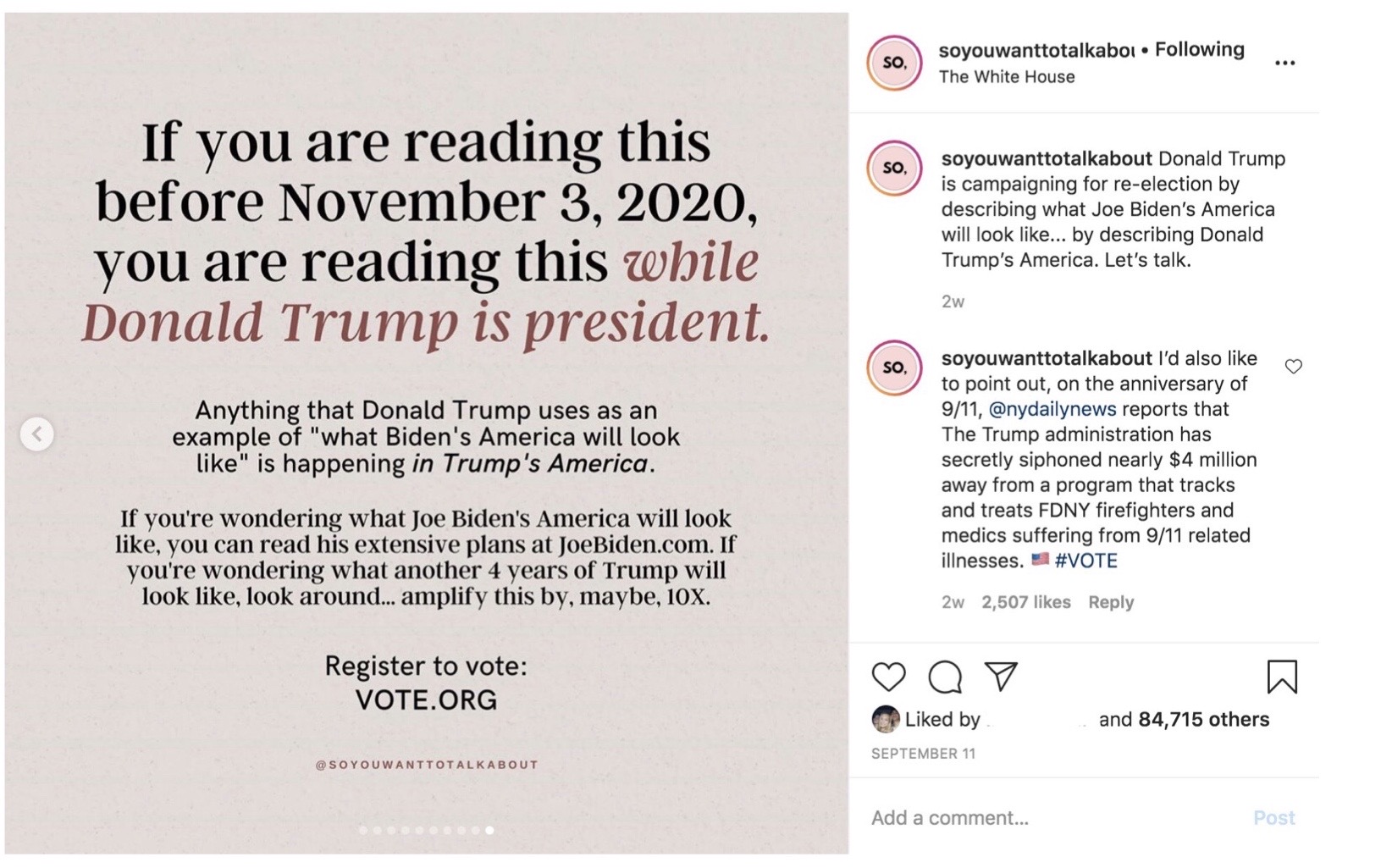

Furthermore, while social media has always reserved a large space for influencers and comedy, Instagram accounts like @soyouwanttotalkabout and @theslacktivists that feature aesthetically-pleasing “Instagraphics” on political issues have also become immensely prominent. These politically-charged posts are wide-reaching among American youth considering Snapchat (62%) and Instagram (67%) have a high usage rate among 18-29-year-olds. TikTok has also become a widely-used platform among young people; 32.5% of 10-19-year-olds and 29.5% of 20-29-year-olds use the platform.

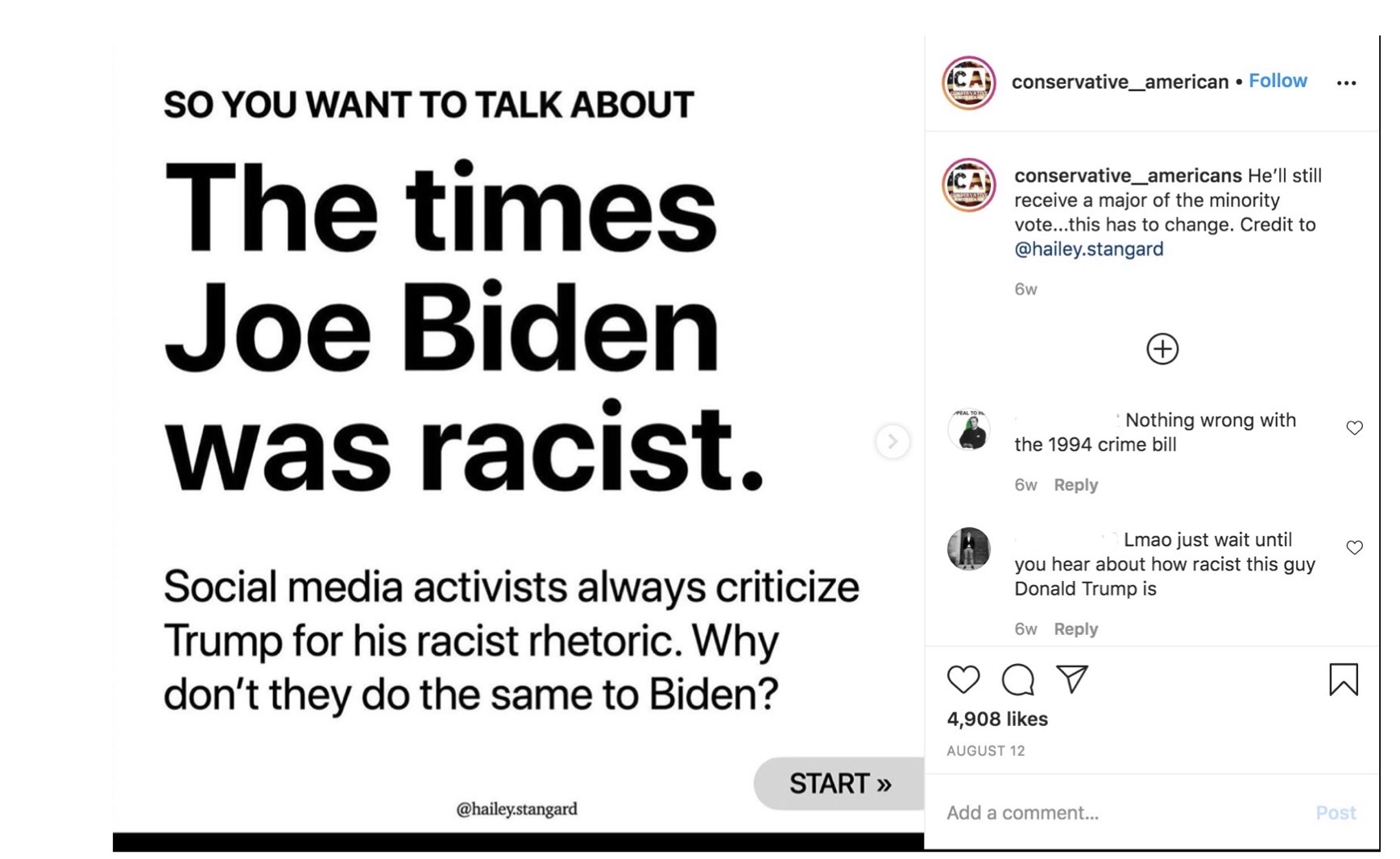

However, this rise in “Instagraphics” has been largely isolated to left-leaning accounts. An article from The New Republic on Instagraphics offered criticism of the trend, writing, “Instagraphics provide an endless source of material with which to interact on these subjects while rarely pushing beyond the political boundaries of the liberal worldview.”

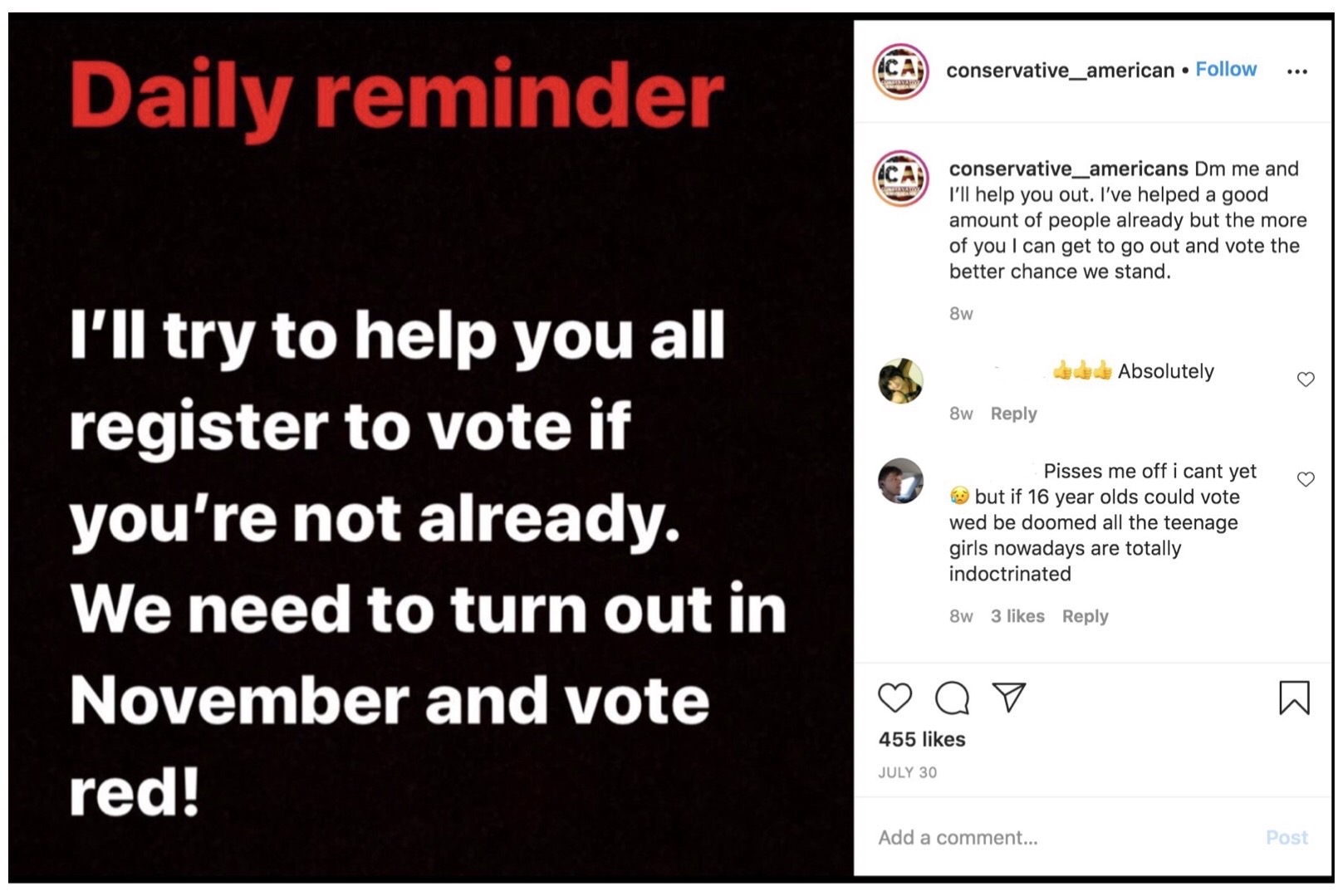

As a juxtaposition, youth-run conservative accounts like @conservative__americans primarily focus on memes. However, creators of these conservative accounts will also post calls to action and similar graphics that further Republican ideology.

Yet, aside from social media, Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE)—an organization devoted to studying youth civic engagement—also encourages higher youth voter numbers.

“When young people vote and participate in civic life, they can bring valuable perspectives to these issues and play an active role in shaping their future,” CIRCLE’s website states. “If youth are excluded or do not participate, our democracy is not truly representing all people and meeting its full potential.”

Who will the youth decide?

On the cusp of a historic, highly contentious 2020 election, what makes young Americans tick? How are Generation Z TikTokers creating political protests over social media? What do closeted Republican students think of their college experience? Why do people feel ashamed when they want to vote third party?

Young voters have the potential to hold 37% of the American vote and “the same share of the electorate that baby boomers and pre-boomers make up.” Where will these votes go? Will this election have the record turnout of youth voters as expected? I don’t have all the answers, but through this analysis of youth politics at DU and across America, I can hopefully help myself and my community ask more questions.

Julisa Mireles-Caraveo, a fourth-year DU student, marched in Friday’s R.A.H.R. protest. It was the second protest she had attended in her life.

“I do my best to be an activist through donating to certain organizations, signing petitions and just overall raising awareness,” said Mireles-Caraveo. “I know it doesn’t seem much, but I believe that a little goes a long way.”

Whether young Americans decide to protest in the streets or sit quietly at home with an edition of the Wall Street Journal, many like Mireles-Caraveo are doing their best to be their own kind of activist.

The Young and Restless will continue next week. Check back on the News section for updates.