For second-year Rosie Contino’s Puksta scholar project, she is creating an online game that will teach sex education to intellectually-disabled students. This project is backed by the Clinton Global Initiative. Rosie is featured as part of The Clarion’s Arts & Life series promoting student work. In an interview with The Clarion, she discussed her project and how she came to be so passionate about the struggles of those with intellectual disabilities.

She is currently looking for computer science students to help her with this project. You can contact Rosie Contino about her project at sophia.contino@du.edu. The Clarion has attached a folder with resources for her project here.

This interview has been edited for clarity and cohesion.

Sara: Can you give me some background for the program you’re creating?

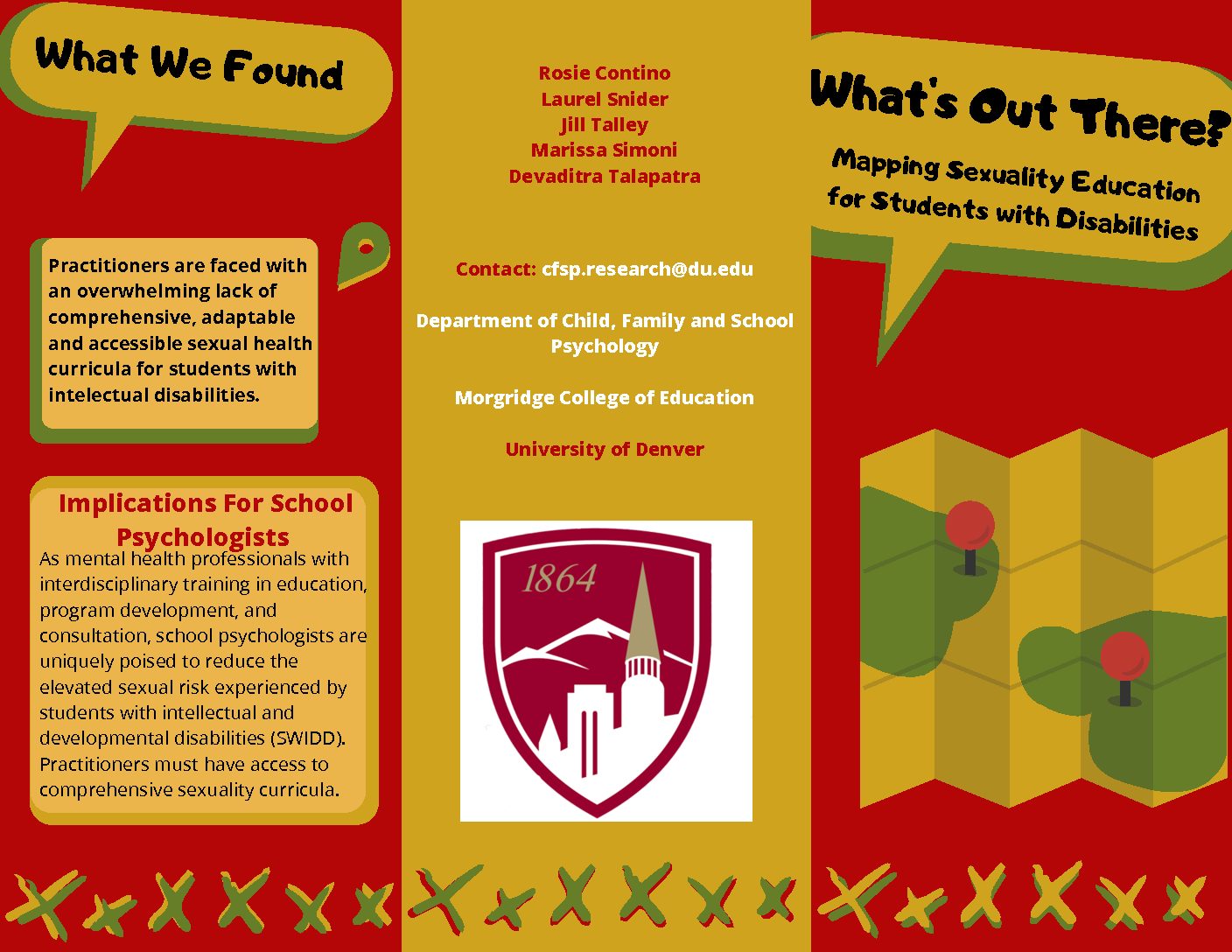

Rosie: Over the past two years, I have been working with a team of graduate student researchers at the Morgridge College of Education. We were analyzing existing sexual health curriculums for students with intellectual disabilities. We found that the problem is that students with intellectual and developmental disabilities are sexually abused at a rate that’s anywhere from three to 10 times more than the general population.

Across the world, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are some of the most vulnerable populations to sexual abuse. They’re also the least likely to report instances of sexual abuse because of the nature of their disabilities. That’s kind of the root problem. We saw that part of the problem is the vulnerability produced from the disability. If you can’t do certain things or you don’t understand certain things, it limits your ability to protect yourself.

But, another thing was the lack of sexual knowledge among young people with intellectual disabilities. We really sought to tackle the lack of sexual knowledge. So, we looked at all the resources out there for parents and caregivers to present sexual information to their students. We found that out of those curriculums, very few were accessible and very few considered contemporary content areas such as pornography, online sexual information, consent, gender identity and LGBTQ+ issues.

What I’m doing with the Clinton Global Initiative is basically my next step in the process of trying to address this issue. I am looking to develop an online game-based learning tool where young people with intellectual disabilities can learn about sexual issues revolving around the Internet. How to properly use the Internet, how to navigate the sexual content that they may see on the Internet, those kinds of things. So, it’s addressing a very specific hole in the curriculums.

It’s going to be meant for caregivers, parents and teachers to use this game as kind of a fun way to not only assess student learning, but also to facilitate student learning about pornography and online dating, those kinds of things.

I’m in contact with a lot of folks in the computer science department working with game development students to try and get a prototype out by maybe the end of next year.

Sara: Why did you want to create this program? What inspired it?

Rosie: My older brother has Sotos syndrome, which causes developmental delays and slower behavior. He has struggled throughout his life with various challenges. His situation wasn’t as intense as a lot of folks, but that inspired me throughout middle school and high school to engage with the special-ed community. I worked with Best Buddies, Respite Care and various programs that connected neurotypical students with students with intellectual disabilities. I was really engaged in that community.

I spent some time in Guatemala as a special-ed teacher for two summers when I was in high school. During that time, it became pretty evident that some of my students were experiencing sexual issues. There were situations where it was evident there might be sexual abuse going on.

In that vein, one of my biggest gripes with the #MeToo movement was how the statistics of sexual abuse towards disabled people were rarely mentioned. The movement was very inclusive. But from this perspective, you can see this massive gap in representation for probably one of the most vulnerable populations. It is another example of how issues concerning disability justice are often swept under the carpet because it’s something that people don’t want to think about. It might make them uncomfortable, but it’s very important.

Sara: What did the process of creating this look like? Who else is involved, and how has this work been supported by the Clinton foundation?

Rosie: The primary people that have been involved are my research team at the Morgridge College of Education. But my advisor for all this research has been Dr. Devadrita Talapatra, and then I’ve also worked closely with a few PhD students. That would be Laurel Snyder and Jill Talley. They are my co-authors on these papers we’re writing. The Clinton Foundation really came through the Puksta scholarship.

In terms of how the Clinton Global Initiative has supported me thus far, they’ve connected me with various funding opportunities. They’ve connected me with a mentor, Ritu Gwani, who does incredible disability justice work in India. She helps Indian women who have physical disabilities with finding employment and starting their own businesses. Every month, we meet and discuss my project and important facets of the community-organizing and social change process.

What’s also really cool about the Clinton Global Initiative is that they divided us into cohorts based on our issue areas. I was in the disability justice cohort, and we met as a large group a few times. There were maybe 20 of us, and everyone was from a different country. People from Senegal, people from India and just people from everywhere. It’s so amazing to see that people are working towards disability equity across the globe. The best thing about the Clinton Global Initiative is feeling like you’re part of a global change network. But, everything has kind of been placed at a halt because of the coronavirus.

Since they’ve postponed their annual conference, though, the cool part is that next year when I go and attend, I will actually have a more tangible product to present. That’s kind of the silver lining that I’ve been looking at.

Sara: How did you tailor the curriculum to cater to those with intellectual disabilities?

Rosie: It’s difficult because when you talk about folks with intellectual disabilities, you’re lumping all of this diversity into one blanket term. Folks with intellectual disabilities have a wide range of needs.

Intellectual disability is defined as having an IQ below 70. But there are folks coming from an IQ of 40, and then there are folks coming from IQ of 70. Those are very different places. The most important thing about developing a curriculum like this is making it extremely adaptable for a variety of developmental levels and needs. It has to be something that can be modified and adjusted based on each individual. Only the student and their caregiver or parent will know what they need. That’s the most important thing we looked at with curriculums.

The other important thing is that things are made and presented in a tangible way. That’s why I wanted to create an online game. Folks with intellectual disabilities have a hard time with abstract concepts.

Saying something like, “When two people love each other very much, they can have private time.” They’re like, “Wait, what does that even mean?” What does it mean that somebody loves another very much? What is private time? Private time could be the two of us right now doing this interview.

Everything needs to be presented concretely. In a video game or online format, you can have pictures and videos. You can have definitions, maybe you scroll your mouse over the word to get the definition for when you forget it.

Sara: What did your learning curve when creating this look like?

Rosie: The hardest thing was realizing that change happens most effectively when it is done in little bite-sized pieces. Initially, I had these huge plans. I was going to start a peer-to-peer education program. But as a college student, I’m involved in a lot of things. My academic passions and post-grad career goals are elsewhere. It just wasn’t going to be possible to do everything in this project. That’s like someone’s life work. That was probably the most difficult obstacle to overcome—my mental conception of how the project was going to go.

Once I got over that hump, I was like, “Okay, maybe I just start with publishing these papers.” Now that it’s being wrapped up, I’m like, “All right. What’s next?” The next step is going to be creating the online game. I will say, though, that I’ve come into a little bit of difficulty trying to collaborate with the computer science department.

I’ve been working with a lot of professors to get the word out. But, a lot of the students don’t want to take on this project. It’s hard. It’s a serious topic. It’s not just for fun. It might not be in their interest area.

Right now, the curriculum and educational piece is there. What’s hard is translating it into some kind of online game that can be used by students anywhere. Working across disciplines has been difficult for me because technical knowledge is not my forte. But if I can find someone with the technical knowledge and combine their technical knowledge with my educational knowledge and this research I’ve been doing, that’s going to be the most effective way to address this problem.

The other thing that’s really hard is recognizing that this project is something I just created. There was no framework for this project. So, everything that exists is because I had to self-start and make it happen. There are days when I don’t feel like crawling out of bed. But you’ve got to do it. If you don’t do it, the folks on your team are not going to do it. Sometimes, you don’t want to self-start. But if you don’t, then nothing’s gonna happen.

Sara: Why do you think this program is important? How would it be implemented as a learning tool in schools?

Rosie: It’s still taboo to say this—which is a reflection on how far we have to go when it comes to disability justice in our culture—but individuals with intellectual disabilities are human beings. For generations, they’ve had their sexuality—which I would argue is a critical component of being human—stripped away from them.

As a human, you have a right to express your sexuality. Even if you’re asexual, you have a right to express it. We have deprived individuals with intellectual disabilities from expressing their sexuality in a safe, healthy way by keeping them away from information about sex. By deeming them to be either asexual or sexual predators. That’s a common, erroneous societal perception of folks with intellectual disabilities.

It takes away a facet of their humanity. This is a population that really doesn’t need that because a lot of the time they’re treated subhuman anyway.

A lot of large towns have a respite center where people with intellectual disabilities can go for all their resources. But if you live in a rural area, you might not have access to those resources that only wealthy folks or those in urban areas have access to. Accessibility is important, and this is going to be a free online game.

I hope that it would be a supplemental tool that anyone could use. It would help supplement a broader sexual health education. It’s important to pursue projects like this because of stigma. There is a large societal stigma surrounding the sexuality of folks with disabilities. By putting something out there that says, “Hey, this is OK. This is how to express your sexuality in a safe, appropriate way,” you’re giving them the tools they need to destroy that stigma.

Sara: Is there any way students can support your project and students with intellectual disabilities?

Rosie: If you are a computer science student and passionate about this topic, please reach out to me at this time! I’m available through email.

As for students, we recently got our first Best Buddies club founded at the University this year. Best Buddies is a program that pairs neurotypical students with students with intellectual disabilities. It allows them to forge friendships and understand and support one another better.

Other ways to support are by reading up on the problem, looking at disability issues and informing yourself. I know problems with disability justice in our community are difficult because there are so many. But being informed will allow you to perpetuate a more accepting and human way of viewing folks with any kind of disability.

Through this time, the Clarion remains devoted to highlighting student work. In this section, we will be featuring podcasts, blogs and projects that have been created and are run by students. If you or someone you know is interested in being featured, email duclarioneditorialteam@gmail.com.