The DU While Native project is a five-part series, explaining the unique situation Indigenous students are in by attending DU, considering the institution’s history in the Sand Creek Massacre; highlighting the struggles these students face on campus and on their journey through higher education; telling stories of their resistance and survival on campus and more. It serves as a space in which Native students at DU can tell their own stories—stories often shared by many Native students around the country. It serves to educate those outside of the community and give insight to the devastating national statistics about the retention of Indigenous students in higher education. Some students have chosen to use pen names to protect their safety on campus. If you have any questions or comments, please send them to duwhilenative@gmail.com.

There has been very little discussion of the Sand Creek Massacre or John Evans’s role in it in any of my classes, or any discussion of Indigenous issues in general. However, there have been a few classes that have discussed the issue, including an advanced writing seminar called “Political Forgiveness.” The professor who teaches the class is Dr. Nancy Wadsworth, one of the professors who was on the John Evans Study Committee. In the class, we questioned how societies can heal for unimaginable trauma, such as the Holocaust, South African apartheid and the Rwandan genocide. We also questioned how DU can move forward from their involvement in the Sand Creek Massacre.

Luckily for the class, this question was a little easier to answer than the others, since the framework for healing had already been set by those who came before us. After the John Evans Report was released in 2014, the John Evans Study Committee released a list of recommendations for the university moving forward. The recommendations were authored by the professors who wrote the John Evans Report and were advised by both Native students and alumni, as well as Sand Creek Massacre descendant representatives.

In the introduction of the recommendations, it states, “We have an opportunity to provide a model of transparency, accountability, and transformation for institutions that have directly profited or indirectly benefited from the displacement of the indigenous communities whose lands and histories they occupy. This moment invites us to bend the arc of history away from the clamor of old apologetics that have caused deep wounds for those whose voices have been silenced and toward justice, healing, and peace.”

The recommendations were put out to reach healing in DU’s community. A healing, as the report states, is not just for Indigenous people and the descendants of genocide but for all people, including “the descendants of those who carried out brutalities and injustice, those who are just now learning and awakening to the mythologies of US History, those still captivated by the popular mythologies of the American West, and those who have been removed from their original land and culture for so long that it seems no longer a memory.”

These 22 recommendations have set up a plan for DU to commit to in order to help the community heal. In 2015, the university introduced a Task Force on Native American Inclusivity in order to accomplish these goals. In introducing the task force, Chancellor Rebecca Chopp stated, “The work of the University includes the mission of healing as well as creating and supporting a world in which such atrocities (the Sand Creek Massacre) will never occur again. It is time for the University to discuss next steps, especially initiatives that will support our Native students, faculty and staff members, and alumni. The University needs to serve the public good in service to and in partnership with Native communities.”

While some of these suggestions have been implemented and some are in the works, others have not been addressed at all. There are also other steps that Native students are advocating the university take outside of the committee’s recommendations. As DU begins to make steps forward, Indigenous students fight to hold the university accountable to their promise to support Indigenous students and to “serve the public good.”

DU’s steps to right their past

One of the first recommendations implemented by DU was to hire Viki Eagle for the position of director of Native American Community Partnerships and Programs. This role was created not only to facilitate outreach to the greater Native community in Denver but to support Native students on campus. I can personally attest to the fact that without Viki’s role on campus, I would have transferred by my second year, and I know that many Indigenous students at DU agree. This role is essential in helping students navigate college and adjust to DU’s culture.

Raelene Woody said, “Of course Viki [helped motivate me to stay at DU]. I think she really helped. I was always in Viki’s office crying.” She explained that without Viki’s support and mentorship, she probably would have dropped out within her first year.

Other steps that the university has worked to implement is transparency about and memorialization of DU’s role in the Sand Creek Massacre. While some effort has been made, such as following the recommendation to create a permanent memorial on campus and disclosing DU’s history during some events such as the first-year dinner, Native students feel the university has not been completely transparent about their history.

“I knew about the Sand Creek Massacre, but I didn’t know about the role DU played in it,” Raelene said. “I think that was intentional by DU because it’s not known. I didn’t even know. And if you dive deeper into DU’s website, or if you ask questions, then it barely comes up. And so I think it’s hard for students to know that upon arriving—to know DU’s history and to know the history of its founders, how it was founded. I [only] found out about two weeks in because I read the John Evans report myself.”

Another recommendation urges the university to “target the recruiting of Native American faculty and staff in all academic units and plan to add at least six new faculty positions for Indigenous scholars within the next five years.” While this goal has gotten a slow start, this year there have been two new positions opened up for Native faculty in both the history and the anthropology departments.

Dr. Elizabeth Escobedo, associate professor of history at DU and the head of the search committee for the new Native faculty for the history department, said, “When we first heard word about a possible line for a scholar in Native American/Indigenous studies from CAHSS, that’s College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences, Dean Danny McIntosh, went forward and asked various departments and programs to come forward with proposals as to why their particular department and/or program should receive the new line for a scholar in Native American and Indigenous studies. And when the history department heard about this, we brought it before the entire department, and there was unanimous support that we should indeed put in a proposal for that position. We were very excited about the possibility of having a scholar in Native American history. That had been the dream of many of us for a long time… So we put forward our proposal and ultimately heard word that we were granted the new line, and we could move forward to hire a scholar.”

She talked about the importance of hiring an Indigenous histories scholar for their department. “When we wrote up our proposal, we really wanted to focus on the importance to diversify the curriculum, both in the history department and within the common curriculum requirements. So our hope was that whoever would be hired could develop not only history courses in Native American history, but then also provide courses for the larger common curriculum. I think that sends an important signal to students on this campus and incoming students who are beginning their college careers that not just history, but Indigenous history is critical to a liberal arts education. And that, in fact, inclusive excellence is impossible without acknowledging and including Indigenous people.”

These new faculty, both in the history and anthropology department, will start at DU next fall.

Native students hope for more

While DU has made some progress on the recommendations, there are some recommendations the university has not implemented yet that students are advocating for, such as establishing a Native American Studies major/minor. While DU’s College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences (CAHSS) has implemented a new Critical Race & Ethnic Studies minor, NSA hopes that the college will give Native studies its own minor or major as the recommendations suggest rather than umbrellaing it under the ethnic studies minor.

Native students are also advocating for things not mentioned in the recommendations, such as a Native Cultural Center where Indigenous students could have their own space to study, relax and find a place away from the struggles of DU’s culture.

“If we had our own cultural space on campus, I feel like it would be a little bit easier to feel safe being a Native student on this campus,” N. Rose said. “I feel like a lot of minority students on campus are targeted in some way, shape, or form. We all know what happens here. There’s a lot of negative experiences that go on because this is a predominately white institution. And particularly, it’s a predominately white institution where people are coming from rich families. Every experience we have they have no way to connect to it. So if there was a space Native students could have on campus, it would, I think, be greatly beneficial to helping them feel like they have a right to be on this campus.”

Salma Ramires Muro agreed with N. Rose, “[Having a Native Cultural Center on campus] would make me feel so happy because I’d be able to walk into a building that doesn’t feel too white and be able to feel at home. Cause honestly, if I walk into any building on campus, I feel out of place. So having that location—a building or bungalow or small house—that is strictly for Indigenous students, by Indigenous students and by the community would be great.”

Indigenous students have also spoken out against DU’s investment in the fossil fuel industry. In a letter NSA wrote to the Board and Trustees in 2017, they stated, “Fossil fuel industries exploit our sacred land and continue to break treaties. Construction and operation of fossil fuel extraction infrastructure will allow for the continued violent victimization of our men, women, and children. As an institution of higher learning, we have exceptional research at our disposal which can help us transfer investments into industries of the future. It will also end the cycle of destruction aimed towards the original peoples of this land who are a part of this Nation’s, and more specifically the University of Denver’s colonizing history.” The university has not responded to NSA’s letter or request at all.

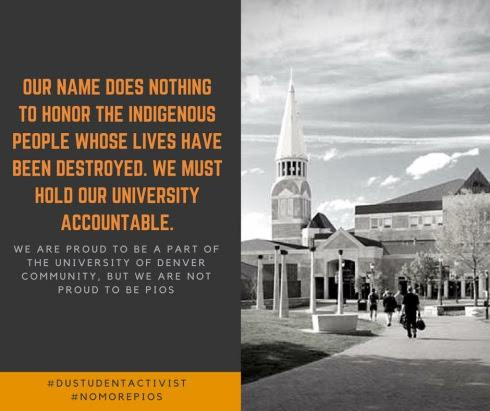

Another request from Native students is to change DU’s “Pioneer” nickname and put in place a new mascot to replace the former mascot still celebrated on campus, Boone. Despite many protests and meetings, the Board of Trustees decided to keep the “Pioneer” nickname in January of 2018.

In response, NSA wrote in their petition to change the nickname, “[The ‘Pioneer’ nickname] represents the violent history of westward expansion, settler colonialism, oppression, genocide, and the systematic violent displacement of Native people from their lands. ‘Pioneer’ also represents the history that DU was a part of. Founder John Evans was complicit in the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, the same year that DU was founded. In the findings from the John Evans Study Committee, it was stated that John Evans is culpable for the Sand Creek Massacre. This is exactly in the spirit of a pioneer. Pioneers killed Indigenous people and stole their land. Pioneers do not represent the spirit of the student body at the University of Denver and it must be changed. DU has said they are dedicated to inclusive excellence. They have promised to make up for their wrong doing to Indigenous people in the Denver community. Yet still, they refuse to show any action behind their words. They continue to participate in modern-day violence against Native communities.”

Though the university has refused to change the “Pioneer” nickname, NSA’s demands have not been completely unheard. Next year, the Student ID office has agreed to allow students and faculty to be able to choose an alternative ID card without the “Pioneer” name on it. So, instead of the label “Pioneer Card,” students and community members will be able to choose a card that simply says “Student Card” instead. This request was completely driven by Native students.

Overall, what Native students at DU want most is a safe, inclusive environment in which Indigenous students are supported and can thrive.

“I just want a more inclusive environment from DU,” said L. Swift. “Like, I know they’re trying, but if you talk to a lot of student alliances here, or people who identify as minorities, they always have stories. They always talk about the hardships here and what they’ve been going through. I want more interaction between those who are higher up on the chain, because I feel like if we do want change we need to be able to talk to them directly.”

Though DU has made strides to move forward, they still have a long way to go to when it comes to creating a better environment and culture for Native students.

Indigenous students at DU paint a picture of the national story

The story of Native students at DU echoes the stories of Indigenous students in higher education across the Nation. The 23 percent graduation rate for Native students in higher education was attributed to a lack of role models, feelings of isolation, racial discrimination, a struggle with the culture in higher education and the everyday challenges of being a non-traditional student. These experiences, and more, were voiced by Indigenous students at DU throughout this project.

Every student that I interviewed spoke about feelings of wanting to drop out or transfer within their first year at DU. I, myself, had thoughts of transferring within my first quarter at the university. If DU and other universities do not work actively and steadily to create a better experience for their Native students, they will not only lose them from their institution, but they will continue to contribute to Indigenous students’ barrier to accessing higher education.

For DU, as a university dedicated to serving the public good and whose history is deeply rooted in the systemic harm caused to Native peoples, I call on them to become a leader for other universities and to respond to their Native students’ concerns to create an environment at DU that encourages these students not to just to survive but to thrive in higher education and beyond.

Overall, these stories serve as a testament to Native students’ resiliency—on campus and off. It is a story of triumph, strength and resistance. It is a story that tells how Indigenous students in higher education are fighting for a better future for themselves, for their families, and for those to come after them.