One of the biggest debates in college sports history is whether student-athletes should be compensated beyond academic scholarships for playing collegiate sports. The landscape of college sports has changed dramatically over time, and now paying student-athletes is a common reality.

What is NIL?

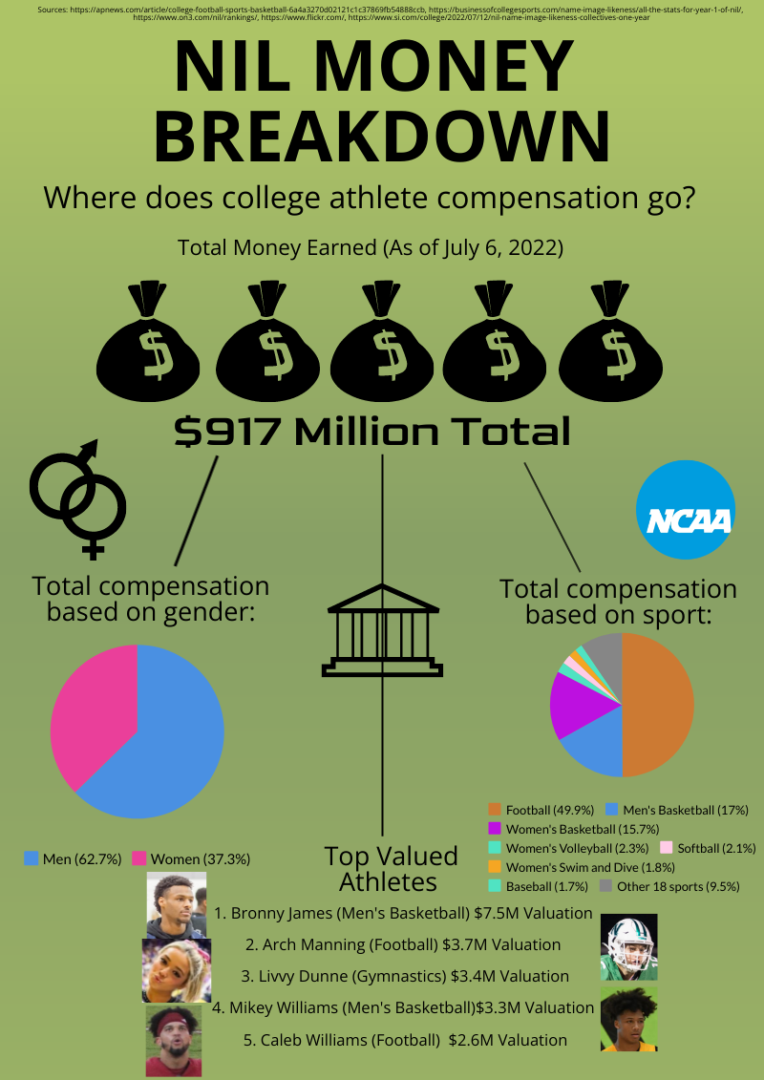

College athletes can now be paid through their right to profit from their Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL). According to On3, the biggest tracker of NIL deals in college sports, it is not a way for universities to directly pay student-athletes, but it is a way for them to earn money through advertisement, memorabilia or appearances at events from outside businesses.

Some of the top athletes in the country can make upwards of six figures in NIL deals. Former Alabama star quarterback Tua Tagovailoa earned $25,000 per advertisement he posted to his social media pages. LSU gymnast and Tik Tok star Olivia Dunne etched a deal with activewear brand Vuori for an estimated six-figure compensation.

Where did NIL come from?

Student-athlete compensation can be traced back to a landmark lawsuit filed by former UCLA basketball player Ed O’ Bannon against the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). O’ Bannon saw himself on the NCAA-sponsored college basketball game created by EA Sports and filed a lawsuit after he was not compensated or inquired to consent to the use of his name, image and likeness.

O’Bannon and his other defendants won the case in 2015 in argumentation that the NCAA acted as a monopoly when dealing with athlete compensation. O’Bannon and his lawyers argued that college athletes should not be considered amateurs given the profits the NCAA brings in. More lawsuits followed against the NCAA, and soon lawmakers in Washington D.C. were pushed to make a national standard of NIL legislation by the NCAA.

The NCAA pushed for this legislation in order to defy the pressure placed by states such as California, New York, and Florida. Congress still has not passed any federal NIL legislation, but the NCAA finally adopted NIL policies and frameworks that went into effect on July 1, 2021.

How has NIL affected DU Athletics?

The era of NIL in college sports was born. Soon after the NIL policies went into effect, universities across the country quickly adopted their own policies and athletes were given the opportunity to profit from their name, image and likeness. The University of Denver was one of the universities to quickly adopt NIL policies, publishing their policy manual the same day the NCAA policies went into effect.

Four months later in Nov. 2021, DU announced a partnership with INFLCR, a platform dedicated to bridging the communication gap between student-athletes and businesses. Student-athletes can send content to brand ambassadors who then post the content to social media and measure engagement with the athlete’s content. The process involves the student-athlete alone, as NCAA policies prohibit universities from being involved.

“While highly supportive of NIL, DU Athletics is not a facilitator in or involved in any way with NIL partnerships,” said Vice Chancellor Josh Berlo and Assistant AD Jason Kesner in a joint statement. “We are committed to continue to provide a platform for NIL connectivity.”

The DU athletic department announced on March 16, 2022, that the relationship with INFLCR had expanded further with the creation of a platform called “The Pioneer Exchange.” The platform would act as the central place for student-athletes to directly connect with businesses wanting to inquire about NIL deals.

DU athletes have since taken advantage of The Pioneer Exchange to utilize their NIL rights. According to Berlo and Kesner, the university is not allowed to give numbers on how many NIL deals DU student-athletes have been a part of, but one NIL deal involving a DU athlete, in particular, garnered media attention.

Denver men’s basketball player Carlos Fuentes is believed to be the first student-athlete in the country to negotiate a NIL deal for his teammates. He negotiated a deal with Saucy’s BBQ Grill on University Blvd on behalf of teammates Tevin Smith, Tommy Bruner and Ben Bowen. Each received NIL compensation for their advertisement posts of the BBQ joint.

Fuentes is an international student and NCAA rules prohibit players with international status from utilizing NIL rights. But that did not stop Fuentes from being part of the new era of college sports.

“I cannot get any endorsements, I can’t get any money, but I can be the guy who gets the deals for other teammates,” Fuentes said in an interview with CBS Sports. “I’m really excited. I’m very passionate about this and this is just the beginning. It just motivates me more to keep going, get more players, more deals, more local places.”

Problems with NIL

Although the surface evaluation of the NIL environment looks admirable, many problems have already occurred since the start of NIL in 2021. The biggest concern is businesses and collective groups having the ability to recruit players to universities unethically.

Collective groups have sprouted up as the result of the lack of NIL regulation, and according to On3, “pool money from boosters and business to help create NIL opportunities for student-athletes.”

Typically, the pool of money is equally distributed among the athletes of a certain program. For example, South Carolina women’s basketball head coach Dawn Staley brokered a deal with its collective group called “Fear the Wave ” to get each Gamecock player opportunities to earn $25,000 through activities sponsored by “Fear the Wave”.

The problem with collective groups is that it has become a method of a betting war for recruits across the country. Collective groups across the country try to entice recruits into lucrative NIL deals with the promise that they will play for their respected university whether that be straight out of high school or through the coveted transfer portal.

A recent news story involving high school quarterback Jaden Rashada and the University of Florida showcases this collective group problem. Rashada backed out of his recruitment with the Gators football team after it was reported from insiders that his estimated 13 million dollar NIL deal fell through. Rashada is now signed to Arizona State University, and it is reported that no NIL money is involved now after the national embarrassment with the Florida football team.

Crimson and Gold Collective

Jack Reis, president of the Crimson and Gold Collective, hopes to navigate away from the existing problems and create a new perspective on how collectives can impact the college sports landscape.

The collective was just recently introduced on social media on May 15, and Reis said the main goal for the Crimson and Gold Collective is to not make players rich but to give them the right experience on campus.

“We are not talking about cars, boats, apartments and stuff,” Reis said. “This is not life-changing money and we are not making people rich. We are trying to give them an experience that is commencing with the rest of the student body.”

The Crimson and Gold Collective works with outside businesses to give players opportunities to earn NIL compensation through activities. These activities include working for local non-profits, running basketball camps, product promotions, event attendance, social media posts and ambassadorships.

As of now, the collective only works with the players on the men’s basketball team. Reis would love to see the collective expand to other programs in the future but it is not a possibility right now.

“We would love to be able to support every program but again it comes down to a bandwidth thing,” he explained. “I can see a future version in the Crimson and Gold Collective where we get more folks on and they work separately on different programs but that is something we just don’t have going on right now.”

Reis is a former DU graduate and a fan of the men’s basketball program. He explained that the collective group was also formed to help the team succeed and compete in the Summit League, which is also seeing growth of collective groups.

“We initially did not think [collective groups] were going to be a big thing and necessarily touch some of these smaller leagues, but it really has,” Reis explained. “Especially with all of these guys moving around in the transfer portal. Some of these schools that prioritize athletics and the athletic experience, they have been ahead of the ball and ahead of what we have been up to.”

The collective has already been discussing deals with businesses around the Denver area for the men’s basketball players and according to Reis, the players have been also discussing their desires to be more involved with the community.

“We want them out in the community, giving back to the community and raising their visibility,” Reis said. “Multiple of them have come to me chomping at the bit to give back and they are just excited.”

Reis said he does not get paid for his involvement with the Crimson and Gold Collective and overhead costs are only dedicated to the functioning of the collective’s website. He is excited about the future of the collective and wants people to understand his uplifting perspective.

“It’s by the people, for the people,” Reis explained. “This is something I want to live on into the future long beyond whatever my involvement is with it.”

What’s next for NIL?

Although NIL has arguably changed the landscape of college athletics and NCAA leadership, the rollout of this new environment has not been ideal. State legislation has conflicted with NCAA policies and it’s unclear how NIL policies will apply to high school athletes.

“First, I fully support student-athletes utilizing their personal brand for their benefit. This is great career-building experience,” Barlo said. “However, the rollout of NIL has been disjointed at best driven by a patchwork of state laws, little standardization, and some unintended consequences.”

The fine line between professional and amateur continues to be blurred and the need for national legislation continues. States continue to pass laws, the latest being Nebraska and Oklahoma which are requiring passage no later than July 1, 2023. These laws give guidelines for what NIL will look like in the state and outline rules that athletes, universities and businesses in the state must follow. But still, no national legislation has been passed.

The overarching fact of the matter is this: NIL is not going away any time soon, and universities and collectives must adapt to keep up with the ever-changing environment.

“We don’t know what the landscape is going to look like in the future,” Reis explained. “We are just trying to do right by the program right now and we will make changes along the way.”