The recent introduction of OpenAI’s ChatGPT software has further vivified discourse concerning artificial intelligence and its interaction with humanity. The chatbot software is both a transcendent yet startling fixture in our species’ ceaseless endeavor to perpetually enhance our technological capabilities.

In the context of academia, a probable ambiance most readers of this publication find themselves within, ChatGPT is an effective tool for providing a student with expedited solutions and answers without them having to apply themselves or engage in the process of critical thought and analyses, the fundamental objective of education.

What is an effective tool for students is a troubling dilemma for professors, whose role is to ensure students are appropriately engaging with and benefiting from assignments and course material. However, artificially intelligent technology extends beyond the classroom, pervading every measure of society.

Operating in concert with technologies ranging from search engines to social media, artificial intelligence encourages the absence of effort and agency. It depletes our species’ capacity to learn, our means to adequately communicate, and our ability to both consciously and intellectually explore our environment, exercising purpose and functionality. In continuously developing and introducing various technologies that facilitate, expedite or simplify basic services and functions, we are sacrificing our biological intelligence.

This is merely an incipient moment in our species’ devolution into a period of what mathematician John von Neumann defines as the Technological Singularity, the theoretical condition that could arrive shortly when a synthesis of several powerful new technologies will radically change the realities in which we find ourselves in an unpredictable manner. The singularity would involve computer programs becoming so advanced that artificial intelligence transcends human intelligence, potentially erasing the boundary between humanity and computers.

Such a singularity is realized through what mathematician Irving John Good defines as the intelligence explosion.

“Let an ultra-intelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man, however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultra-intelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be far left behind. Thus the first ultra-intelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make,” Good said.

While often forsaken as theoretical, it is important to realize that artificial intelligence will inevitably mature into ultra or superintelligent machinery, barring an extinction-level catastrophe. Neuroscientist and philosopher Sam Harris identifies A.I. researchers referencing “time” when they want to be reassuring as one of the most frightening things about artificial intelligence.

“One researcher has said, ‘worrying about A.I. safety is like worrying about overpopulation on Mars.’ This is the Silicon Valley version of ‘don’t worry your pretty little head about it.’ No one seems to notice that referencing the time horizon is a total non sequitur,” Harris said.

Harris further emphasized the inevitability of A.I.: “If intelligence is just a matter of information processing and we continue to improve our machines, we will produce some form of superintelligence.”

Artificial intelligence is employed within every configuration of technology we use, inflicting profound damage upon human health and biology. When using standard features of navigation like that of Google Maps or GPS, components of our brains turn off and our memory weakens. The detrimental impacts of social media are also well-documented, determined as inhibiting focus and productivity and being harmful to our mental and physical health.

We embrace dating apps, swiping for love and companionship at the expense of personal, natural intimacy. The same is true for pornography, where humans have begun to increasingly engage in sexual affairs or intimacy through virtual reality or robots. Through robots, artificial intelligence has infiltrated our judicial system, with some being considered to represent clients, prosecute or adjudicate in the court of law.

Artificially intelligent technology has begun to win art contests, compose music and defeat us in our competitive games, with the famed chess match of Kasparov v. Deep Blue as the most prominent example. We have cast aside any semblance of privacy, allowing developers to harvest our data, collect information on our consumer habits and track our physical movements.

Scientific researchers and medical professionals have warned humanity of the immeasurable harm our overdependence on technology inflicts upon our physical, biological, mental and emotional health. Yet, as the generation that supposedly champions mental health, science and equality, our behavior fails to change. This too concerns Harris regarding artificial intelligence.

“One of the things that worries me the most about the development of AI at this point is that we seem unable to marshal an appropriate emotional response to the dangers that lie ahead,” he said.

Through a comparative analysis, let us consider our emotional responses to climate change and smoking. While we are beginning to experience the detrimental effects of climate change, it is expected that future generations will be forced to confront the premier consequences of the devastation exacted by climate change and our collective impact on the environment. This impending peril is met with international media attention, extensive social movements and campaigns, and a plethora of legislative and policy efforts. We assemble an appropriate response to climate change because we recognize it as an existential threat to our planet and species.

After epidemiologists determined in the 1940s and 50s that smoking and the use of tobacco were associated with the contraction of lung cancer, smoking and tobacco use in the U.S. decreased dramatically. According to CDC data, since 2002, there are now more former smokers than current, and 61 percent of adults who have ever smoked have quit. Society assembled an appropriate response to the significant health implications of smoking.

Why is the established threat and harm imposed by technology and artificial intelligence not afforded similar scrutiny?

Our dependence upon technology has become so remarkably severe that we are unable to properly assess and react to these particular risks that threaten our health. The proliferation of artificial intelligence and the introduction of superintelligent machinery is only intensifying this severity.

Excluding the erosion of human biology and intelligence, what should further concern our species is our willingness to surrender our purpose and fate to artificial intelligence. Philosopher Nick Bostrom illustrates this very fear.

“We need to think of intelligence as an optimization process. A process that steers the future into a particular set of configurations…A superintelligence with such technological maturity would be extremely powerful, and at least in some scenarios, it would be able to get what it wants. We would then have a future that would be shaped by the preferences of this AI,” Bostrom said.

This future is not prognostic, for it has already arrived. As the demand for media literacy and technological proficiency in the labor market expands, institutions of education and higher learning increasingly implement and encourage programs and curricula that focus on technical learning.

As education and job training progressively emphasize technical learning, intelligence becomes solely valued and measured as it applies to technology. In a future where artificial intelligence has seized all intellectual work, whereas every conceivable job, service and function performed by humans has been ceded to superintelligent machinery, our only serviceable purpose as a species will be to maintain this technology.

Concentrations in the liberal arts will no longer be necessary, as superintelligent machinery would conceive our ideas, draft our policies, compose our art and produce and broadcast our entertainment. The same is especially true for concentrations in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and computer science (STEM).

Such machinery would conduct our experiments, invent our contraptions, design and construct our products and solve every equation. We would be creating the technological equivalent of a God; a provider of every innovation, every service, every resource. With technology established as our sole discipline, humanity will be rendered to eternal servitude to this God.

What would occur under our current political, social and economic order following the expulsion of all intellectual work?

“It seems likely that we would witness a level of wealth inequality and unemployment that we have never seen before. A few trillionaires could grace the covers of our business magazines while the rest of the world would be free to starve,” said Harris.

Today, even without the presence of superintelligent machinery, employers endlessly pursue methods of minimizing the costs of labor through reducing human employment and outsourcing labor to machines, maximizing profitability. Superintelligent machinery would naturally be the ultimate cost-effective and lucrative labor-saving device.

When intellectual work is absent, corporations will consist only of their affluent founders and executive members, while their machinery would perform all labor for them. Society would be divided into two separate classes: those who control the production and delineation of all information and services, and those who consume it.

Politically, this future would be susceptible to technocratic authoritarianism, a governing of society not by democratically elected officials but by technocrats guided by the imperatives of their technology.

“What we need to fear most is…how the people in power will use artificial intelligence to control us and manipulate us in novel, sometimes hidden, subtle, and unexpected ways,” said sociologist Zeynep Tufekci. “Much of the technology that threatens our freedom and our dignity in the near-term future is being developed by companies in the business of capturing and selling our data and our attention to advertisers and others.”

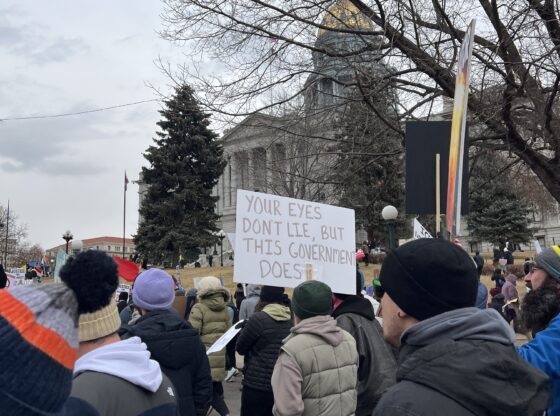

What of socio-politics? When citizens within society are not inundated with misinformation and disinformation, they’re consuming competing ideas carefully tailored by algorithms employed by media and technology entities, heightening political polarization and making public debate, discourse and compromise impossible.

How might superintelligence exploit this erosion of democracy? Would this technology be utilized to establish uniformity in thought and ideas or perhaps intensify our divisions as designed?

As we acquiesce power to A.I. developers to define what humanity’s preferences and values are, either is possible as long as profitable, and both are catastrophic to democracy.

“If the people in power are using these algorithms to quietly watch us, to judge us and to nudge us, to predict and identify the troublemakers and the rebels, to deploy persuasion architectures at scale and to manipulate individuals…using their personal, individual weaknesses and vulnerabilities…that authoritarianism will envelop us like a spider’s web and we may not even know,” said Tufekci.

Overt authoritarianism, that of military and executive coups, dissolving of constitutions and eradication of civil and human rights would no longer be necessary to employ to control a populace. Technocratic rule will be effective in guiding and remodeling our behaviors, attitudes and perceptions, preventing us from psychologically identifying democratic backsliding and tyranny when and where it occurs.

Additionally, how might our nation’s authoritarian adversaries utilize this technology to subvert democratic interests and those of our allies? This technology could be used by dangerous, authoritarian regimes to effectively interfere in democratic elections, disrupt our infrastructure, destabilize diplomatic interests and wage war.

To successfully resist the materialization of a technocracy, society must concentrate its efforts on combating the proliferation of technology and artificial intelligence. However, dependency and hypocrisy are the prevailing obstacles to achieving this aim. The same individuals distracted by their repudiation of capitalism, who perhaps detest and protest our planet’s most prominent, wealthiest billionaires, including contemporary figures such as Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, Elon Musk or Bill Gates, continue to purchase most if not all of their products through Amazon. They actively seek the latest iPhone, smartwatch and AirPods through Apple, obtain an electric car through Tesla or spend thousands of dollars to secure the latest laptop, computer or programs through Microsoft.

Meanwhile, magnates like Mark Zuckerburg envision humanity living in his Metaverse, casting humans out of society into a fragmented, virtual space, left to no longer physically organize and communicate with one another. Yet, we continue to engulf ourselves in his social media products on an incessant, daily basis. We have not provided technocrats like Zuckerberg a reason to believe he will not be successful in this endeavor.

Now, let us assume we eventually concluded that such an apparatus was acting to the detriment of humanity and it was necessary to terminate it. Could this even be possible? The answer is no, for the following reasons: First, we will have become too dependent on it. The technology itself will have become our only tool, service and purpose. Second, through our dependency, technocrats will have accrued enough wealth and political dynamism to sustain permanent economic, social and bureaucratic supremacy. Third, partially by virtue of the two preceding reasons, there is no off-switch.

“We are an intelligent adversary. We can anticipate threats and plan around them. But so could a super-intelligence. It would be much better at that than we are,” said Bostrom.

Even if we eventually regret this technology, we will be unable to abandon it, and those who will suffer the most will be our children and grandchildren. Every generation lights a fire it cannot itself put out, and I am afraid this will be ours. Cue Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start the Fire.”

While artificial intelligence is certainly a revolutionary innovation that has and will continue to make extraordinary progress in engineering, science and health care, we must accurately assess the technology’s overwhelming risks and fully comprehend what we are in the midst of building.

Thus, we find ourselves in the dawn of a new technological renaissance, our final renaissance. As mankind becomes increasingly anxious, depressed, isolated, less-productive and less-intelligent, superintelligent technology being our last invention is apocalyptic.

There is no purpose in warning against opening the pandora’s box that is artificial intelligence, for it was already pried open during the infancy of this century. Thus, I am left only to encourage that we refrain from further proliferating artificial intelligence and superintelligent machinery to a degree where it can no longer be properly monitored or controlled.

I would suppose it is tragic that I used ChatGPT to compose this entire publication. Or did I? It is because I can stoke any degree of uncertainty as to how this was written that shows why this technology should petrify us. In a future of technological singularity, where the distinction between computers and mankind is eradicated and life itself is dominated by superintelligence, how could we possibly distinguish the human from the artificial?