Redlining is one of the starkest yet underrepresented systemic barriers of policy-making in the 20th century. It has effectively allowed the federal government to segregate the country by discouraging financial institutions from lending out healthy mortgages to people that live in areas deemed to be “risky.” Risky in the sense, is often associated with the racial makeup of a completely false, discriminatory and racist thought process.

The process began with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal,” a series of social programs created from 1933 to 1939. The programs that were established aimed at lifting “the nation out of the Depression” through governmental assistance as a means of building wealth. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was one of the more important of these programs and helped many Americans buy houses at an affordable rate, ultimately increasing generational wealth. The catch was that it only benefited white America.

To understand how the FHA discriminated against people of color, it is first important to understand what it did. At its core, it acted as an insurance policy for banks that distributed loans to buy houses. Therefore, when a problem arose and a borrower could not pay the loan, the FHA would step in and “pay a claim to the lender for the unpaid principal balance.” This created a sense of safety for the lenders that allowed them to “offer more mortgages to homebuyers,” according to the FHA.

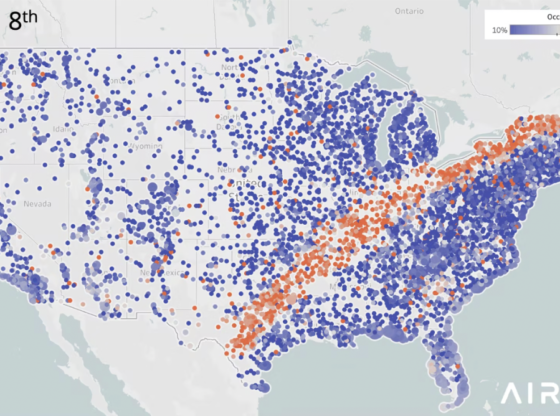

However, there were requirements issued by the FHA and the Home Owners Loan Corporation that decided the manner in which these loans would be backed. The Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was a government-sponsored corporation that would go into neighborhoods and rate them based on their perceived risk of faulting on loans.

This rating process was predominantly based on the racial makeup of the neighborhood. Areas consisting of predominately non-white people were given the worst grades. They would then collect the grades of all the given areas “and pass that information on to lenders” where they would decide the mortgage rate. Areas with a poor grade would receive loans with higher interest rates, imposing a higher financial burden and increasing the possibility of a default.

The FHA itself had its own requirements, all of which were laid out within the underwriting manual. This manual provided a set of guidelines, especially for real estate developers, that needed to be met in order for mortgages to be backed by the FHA. One of these requirements was that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities.” This manual also established the need for restrictive covenants and deeds, documents that legally prevented homeowners from selling to African Americans. These deeds supposedly helped to “provide the surest protection against undesirable encroachment and inharmonious use” in order to protect the long-term ability to invest in the properties.

These racist policies were ultimately reversed with the Fair Housing Act of 1968 which prevented discrimination on the basis of race in relation to buying, renting or taking out a mortgage to purchase a property.

This act however did nothing to address the damage that had already been done. According to an ABC News analysis, “20 of the nation’s top 100 metropolitan areas have an ‘extreme dissimilarity index of 50 or higher,” which means that at “least half of the population would have had to move to another neighborhood in the area to achieve total integration in 2019.”

The issue has also persisted in regards to the disparity in generational wealth. Most Americans today get their wealth from the equity they have in their homes, and these same properties are passed down from generation to generation, all the while increasing in value.

The educational fallout of redlining is also grim. Families with more wealth typically move away from urban centers, the same centers that acquired the worst grades before the Fair Housing Act, taking potential tax money that funds the education system. This creates areas with more substantial funding for primary academics, creating a perpetuating effect that makes it more difficult for people in historically exploited areas to reach secondary education.

Our government created and perpetuated this problem, but getting rid of or repairing a malicious set of policies does not fix the situation. That’s just like putting a new coat of paint on your house. It makes it look prettier, but under that layer of paint, the damage still exists. What the New Deal established was a legal means for wealth to be acquired and distributed at an unequal rate, privileging the generations that followed to secure themselves financially in a society where others were not legally able to.

Justice is not achieved by saying something that happened was wrong. If a bully at your school takes your lunch money, and a teacher makes him say sorry to you, would you be satisfied? Chances are no. Nor will the disenfranchised be satisfied until what was taken from them is given back. The message here is that this is a problem created by our government, and we should expect our government to give to the people what it stole from them: wealth and economic safety. The ensuing problems of redlining, from education to wealth and housing inequality, will not be solved until this happens. It will only keep perpetuating and manifesting itself in different ways.

One starting point could be reparations. If the Fair Housing Act of 1968 represents the bully saying sorry for what he stole, then reparations would represent the bully giving back what he stole. Ta-Nehisi Coates illuminates this aspect in his essay “The Case for Reparations” when he states that “when we think of white supremacy” we “should think of pirate flags.” The concept of reparations is a divisive one, but we need to remember that our country has the financial backing to do some extraordinary things for its people. While this seems as if it would divide our country, even more, Coates sums up beautifully the deeper chords reparations could potentially strike:

“Won’t reparations divide us? Not any more than we are already divided. The wealth gap merely puts a number on something we feel but cannot say—that American prosperity was ill-gotten and selective in its distribution. What is needed is an airing of family secrets, a settling with old ghosts. What is needed is a healing of the American psyche and the banishment of white guilt.”

Reparations would not only be justice for those who have been historically left out, but it would be justice for the entire country. It would be justice for the generations to follow and would set America on a path to finally live up to what it has always wanted to.