This article is part five of a nine-part series that focuses on climate change. More specifically, this series will go in-depth on the human disconnect of accepting the reality of climate change, the role of the media, the power of student voices in environmental movements, climate science, sustainability and the pressure for the University of Denver to divest from fossil fuels.

The list of universities divesting from fossil fuels is growing. Student movements at Harvard University, Yale University, University of Michigan, University of Minnesota, Whitman College and more have been the catalysts for change by demanding their college to divest.

Whitman College had a club called Divest Whitman. They met weekly, and had breakout groups that worked on different aspects of the campaign like outreach to student groups or administration, writing proposals, leading protests and being in contact with the Board of Trustees. Whitman’s endowment ranged from $400 to $500 million.

The University of Michigan (UM) partial divestment is thanks to Climate Action Movement (CAM). CAM is a “coalition that pushes [UM] to align itself with the urgent need for climate and environmental justice through campaigns including, but not limited to carbon neutrality, divestment, climate resiliency, public power, and intersectional power building with local justice campaigns.”

In March of 2021, UM divested from oil, coal and the top 200 fossil fuel companies. UM’s endowment is roughly $17 billion with $1 billion in fossil fuels. To put this number in perspective, the University of Denver’s endowment is $772 million.

The first step to any campaign is solidifying a foundation. This consists of researching divestment, the university’s endowment, reaching out to other student groups, encouraging people to join the movement and more. Every student had a different experience with getting involved with the divestment organization at their university, in this article’s case, CAM and Divest Whitman.

What was the process of the divestment organizations?

For a university to divest they need the Board of Trustees or Regents, depending on the college, to agree to pull out certain investments. Once a college divests, this process happens over a certain period of time, which is discouraging for divestment activists, like Leah Webber, a UM student and member of CAM since 2019.

“UM’s version of freezing fossil fuels was not exactly perfect. There were some investments that they continued to make that were questionable that involved natural gas. Their actual dis-investment announcement was lacking significantly,” Webber said. “It was unclear if they had decided to pull out of investments completely, or let their contracts run out.”

During the students’ activism at Whitman, the board made it more difficult for Divest Whitman to request fossil fuel divestment. They limited the submission of the proposal to once a year. The students speculate that the board did not want to address this issue, and wanted to limit the activists’ power.

“We tried to make Whitman divest multiple times. Every time there was a board meeting, which was two to three times a year, we would have an action. We usually got good participation for the actions. When we had an action, it was fun and it was not hard to get people to join in,” Julio Escarce, a former member of Divest Whitman, said.

Divest Whitman did not back down. The club continuously was planning actions, writing proposals and contacting the administration.

“It took an incredibly long time. An astoundingly long time, in my personal opinion. It was a multifaceted approach. We had people working on demonstrations on campus, which would often coincide with when the meetings were happening, and that is what garnered support,” Caroline Arya, a former member of Divest Whitman, said. “We also worked with the newspaper, writing op-eds. It was kind of a matter of gathering the support needed for the student body and through the faculty and staff. It was a multi-pronged situation.”

The students were feeling angry, defeated and tired with the amount of work they were continuously putting into Divest Whitman. They were wondering what it would take for the university to finally pull out of fossil fuel investments.

“I remember constantly being told that the Board of Trustees are looking out for the future of the college. And I thought, there isn’t going to be a future with climate change. There will be no college if sea levels rise and fires take over the west coast. To have a college not practicing the principles its preaching, is egregious,” Genean Wrisley, a former member who was heavily involved with Divest Whitman throughout her collegiate career, said.

Student activists, like at CAM, spent some time researching the economics of divesting from the fossil fuel industry. “We had multiple economics professors run the numbers on what it would look like to divest from fossil fuels, as well as looking at systems like the UC schools that divested, and we saw that they were better off. Fossil fuels aren’t exactly an industry that’s doing well or going to continue to do well,” Webber said.

The industry is currently in decline, and ranked last out of all of the sectors on the market index, S&P 500, which is less than 3%. This is in comparison to their 30% a few decades ago.

What were some notable protests?

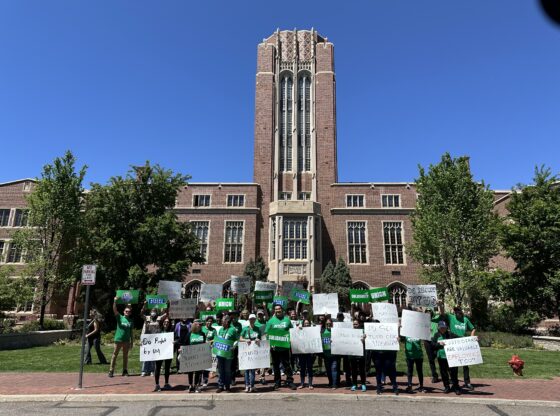

Whitman College has a total of 1,360 undergraduates. When Divest Whitman would hold protests, at least half of the student body would hear about it through different social networks because the word would spread so quickly.

A notable protest within Divest Whitman was the oil spill action where students wore all black and laid on the steps of their academic building and the lawn. The dress code mimicked the aesthetic of an oil spill, and was visually impactful for students. This act resonated with the students, and created a positive impression on campus within the divestment campaign.

“We had speakers from other student groups discuss the way in which the use of fossil fuels is an intersectional issue. That was the most impactful protest, for me personally, because you got the idea that fossil fuel usage and environmental degradation was an issue across the board for everybody,” Arya said.

A few other actions consisted of the frequent use of spray paint on the lawn or a sheet that says “coal kills.” The freshman of Whitman in 2018 had a campaign where they put letters in people’s windows so the residence hall spelled out “coal kills, divest now.”

“Before I got to Whitman, they did a joint wedding of fossil fuels and Whitman College, and that was done right on the steps of our big hall. This happened when the board was in town, and photos were printed in the newspaper,” Arya said.

There was a variety of sit-ins, flyers and white sheets that had written the exact amount of money the university had invested in fossil fuels. These actions would happen in central areas of campus. The main goals of Divest Whitman were to raise awareness of Whitman’s investments and educate the students on the impacts of fossil fuels on the environment.

CAM also focused on educating the students on divestment and planning climate strikes on the same days as the national movements. They also held #FridaysForFuture, an international youth-led movement that began with activist Greta Thunberg. In August 2018, Thunberg skipped school and sat outside the Swedish Parliament demanding action on the climate crisis.

Notably, in March of 2019, roughly 2,500 students and community members of Washtenaw County, MI participated in the global climate strike. The school walk-out was at 11:11 a.m., and consisted of a march around Ann Arbor that ended at the Fleming administrative building at UM. Student activists then led a 7.5 hour sit-in, and were demanding for a one hour public meeting with UM President, Mark Schlissel, to talk about divestment.

Instead of listening to their demands, the police arrested 10 students for trespassing after university hours. This created bad press for UM, and student climate activists believe this was instrumental in moving the divestment campaign forward.

UM had a powerful protest in 2020 that was one step closer to getting the university to divest. The student activists blocked the exits of the board of regents meeting. The students were nervous of being arrested after the sit-in incident. Luckily, no students were arrested, but UM security guards were physically moving activists, so board members could exit the meeting.

“All of the people who had any possibility of getting arrested went through a non-violent arrest training, so they have numbers of legal people to call and everything written down. At the end of the meeting, we had a group block of the exits,” Webber said.

The following meeting, after this protest, UM said they would be freezing all fossil fuel investments for the time being, but this does not mean that UM fully divested. This statement occurred in February 2020, a year before the partial divestment, where UM said they would not invest in more fossil fuels until an investigation has taken place.

What was the final straw for the universities?

Both UM and Whitman College student(s) described the day their university divested as a strange, yet exciting feeling. These students put so much hard work and time into continuously pressuring the university to divest, and it felt surreal when the university actually said yes.

“It was almost like an on-and-off switch, and I think all of the actions that we had done contributed towards that outcome, but I do not know to what degree,” Escarce said. “The way it happened makes it feel less like it’s a model of success and more like we just got lucky.”

Whitman College had a change in the chair of the Board of Trustees before the college decided to divest. Students believe this could have been the main reason, but the continuous protests could have also impacted the board’s decision.

“We submitted a handful of proposals throughout Divest Whitman,” Arya said. “I think the reason for our final proposal being successful was from a combination of being worn down by our various proposals and a change in leadership.”

On the day of divestment for Whitman, it was the end of the school year, so Divest Whitman planned a day of action. The actions consisted of standing outside of the board meeting with signs and talking to board members as they walked outside. The actions were halted when inside that board meeting, the chair decided to fully divest from fossil fuels.

“We all went outside and celebrated. One of my friends gave a speech about how great it was that we succeeded, but we couldn’t stop fighting for justice. It was a very emotional day in a good way. We still had actions planned for the rest of the day,” Escarce said.

The final straw for UM was a combination of the protest outside of regents meeting the year prior, and the board meeting with a panel of climate experts who gave presentations on the pros and cons of UM divesting from fossil fuels. The students believed their disinvestment statement in March of 2021 was wordy and vague, but they still celebrated this win for the environment.

“We wanted to celebrate this step in the right direction,” Webber said. “But it is only a step, and not the end result, and we are not going to stop fighting.”

These student movements and relentless voices are what pushed their university to divest from fossil fuels. These students felt unsatisfied with how the university was investing their money, and they made a change. This left a legacy for future classes to come into the university, and feel inspired by what their predecessors had accomplished.