The following is a Letter to the Editor for the Opinions section.

Today, nearly 800 million people across the world will experience their period. Of these people who menstruate, nearly 500 million will lack basic supplies, facilities and support for managing their periods.

Period poverty is a global issue affecting menstruating people who lack access to affordable, safe and hygienic menstrual products. In these conditions, people who menstruate are unable to manage their periods while maintaining their personal dignity. This issue is further exacerbated for the nearly 231,000 incarcerated women in U.S. correctional facilities who already lack basic human rights.

We recognize that criminal justice systems are not limited to the experiences of women, as access to menstrual products has a pervasive impact on non-binary individuals, transgender people and men in this discussion. However, incarcerated spaces are inherently divided along the gender binary. As a result, the data available on period poverty in prisons is limited to binary definitions which focus on the experiences of predominantly cisgender women.

Incarcerated women comprise the fastest-growing population in correctional facilities in the U.S. In the last 40 years, women’s prison populations have increased 834%, with the majority of this growth occurring in local criminal justice systems such as jails.

The incarceration system was not built for menstruating bodies. Menstruating populations are forced to adapt to systems, practices and policies that are designed for the majority of the incarcerated population, which is predominantly male. Facilities and correctional employees are ill-trained to deal with menstruation. As a result, the vast majority of experiences in incarcerated spaces are marked by stigma and humiliation.

Menstruation and incarceration are both deeply stigmatized issues. Period poverty in incarcerated spaces is a topic that lies at their intersection. The most direct way to address this complex issue is through policy. Inadequate federal legislation inevitably results in limited access to comprehensive hygienic menstrual resources. Despite government efforts, federal policy has failed to impact the nearly 86% of incarcerated women currently held in state prisons and local jails.

The only way to continue the push for a more comprehensive policy is through education. The current lack of research on this topic only reinforces the need to raise awareness.

As sophomores in the DU Leadership Studies Program, we recognize our privilege and responsibility to support incarcerated menstruating populations and bring awareness to the issue of period poverty in correctional facilities. As a year-long service project, we completed extensive research to understand period poverty as it intersects with criminal justice and explored the perspectives of local and national stakeholders.

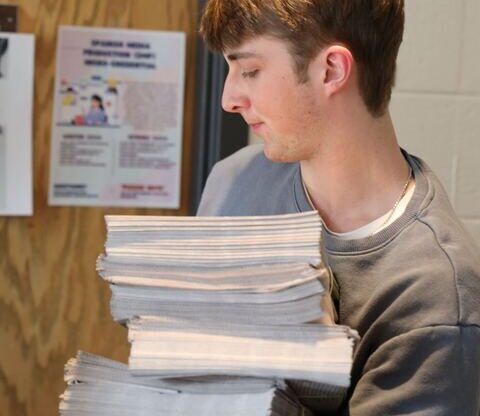

To increase awareness within the DU community, we facilitated a speaker event called “Discourse & Dignity, Period” with DU Happy Tampers to highlight the story of one incarcerated menstruator. Attendees then packed 86 period kits to represent the 86% of incarcerated menstruators who are unaffected by current federal policies. Each of these period kits will sustain a menstruator through one cycle. They have been donated to The Reentry Initiative, which is a local organization that helps formerly incarcerated individuals reenter the community.

Our primary stakeholder, Stacy Lyn Burnett, highlighted her experiences as a formerly incarcerated person who menstruates. As Burnett explained, incarcerated menstruators are often forced to beg for products, barter sex with prison guards for pads or bleed through their smocks.

While speaking at the event, Burnett recalled how ill-informed male correctional officers were on the reality of menstruation. On several occasions, Burnett was told to ‘hold it [her period]’ and was frequently asked how long periods last.

In an earlier interview with Burnett, she shared that she “never really felt great about having to tell a man that ‘No, that’s not enough tampons […]’ I don’t really feel like I need to explain to him that I can’t use one tampon a day—it just doesn’t work like that.”

Understanding this stigma and the resulting misinformation is the tip of the iceberg. Structural barriers such as tampon taxes, prison labor and wages, the school-to-prison pipeline, and disproportionate incarceration rates of communities of color are all part of the complex web that actively demonizes periods in a space where menstruators already face dehumanizing conditions.

While the situation may appear bleak, Burnett shared that it has gotten better: “I am very hopeful because of the attention that this subject has gotten over the past several years,” she said. While conditions have improved in select locations, there is still so much to be done.

The situation is only better because of people who are willing to challenge systemic injustices. But change does not happen overnight. Norms cannot be dismantled unless there is a significant increase in education. We call upon the DU community to normalize conversations about periods and confront systemic inequities in the incarceration system.

In solidarity,

Caitlyn Aldersea, Gabriele Eidukeviciute, Arianna Carlson and Heather Anderson

Pioneer Leadership Program, Class of 2023