This article is part five of a six-part series detailing youth political subcultures and the role of youth political participation and activism in the past and present. By highlighting political activity at DU, this column seeks to find patterns in historical and present-day activism among youth populations. It hopes to shed light on how American youth populations view various political issues in different or similar ways from other youth voters and older generations.

As news of Joe Biden’s presidential win roared through America on Saturday, so too did the predicted trends: more women than men backed Biden, Cuban and Venezuelan Americans swung for Trump in Florida, and young people under 30 overwhelmingly voted blue.

Mainstream media often discusses these large demographic groups in order to analyze how candidates fared across America. As a byproduct, certain groups of young people are overlooked despite their potential to create a sizable dent in elections.

As presented in previous articles for this column, young people do not hold a historically shiny reputation for high voter turnout. Commonly-sourced reasons for this trend are young people’s supposed apathy and lack of solid ideological or partisan association. However, the media has begun to debunk this, stating the constant mobility of young people and lack of a stable home address and transportation make voting less accessible.

Recent studies have shown that people with “older, more educated and more ideological Americans” are more likely to participate in more civic activity, whether it be voting or political activism. In addition, young Americans aged 18-29 have the lowest amount of civic knowledge compared to their older counterparts. Although young people have increasingly shown up in political movements and elections since 2016, the age group is still relatively underrepresented in politics.

Furthermore, the media largely centers the conversation around youth politics around common social identifiers like gender, race, ethnicity, geographic location or religion. However, what about politically disenfranchised groups of young people who don’t fall into these lines and do not have privileged access to technology, physical proximity to political events or education?

Young people who are incarcerated, in the military, or are children of recent or undocumented immigrants all fall into this strange middle ground; they are not conventional and easily categorized voters, yet they have the potential to significantly influence socio-political movements.

Young Incarcerated Populations: Where can they vote and how?

Can people vote in jail? In many parts of the United States, the answer is yes. Considering America has the highest incarceration rate in the world, these populations could effectively sway election results.

According to The Sentencing Project, “the vast majority of persons are eligible to vote because they are not currently serving a sentence for a felony conviction” in local jails. Many are simply waiting for trial or transfers to state prisons, or they are serving misdemeanor sentences. As of 2017, “nearly two-thirds or 482,000” people incarcerated in local jails are eligible to vote, which is a sizable number compared to the few who actually do.

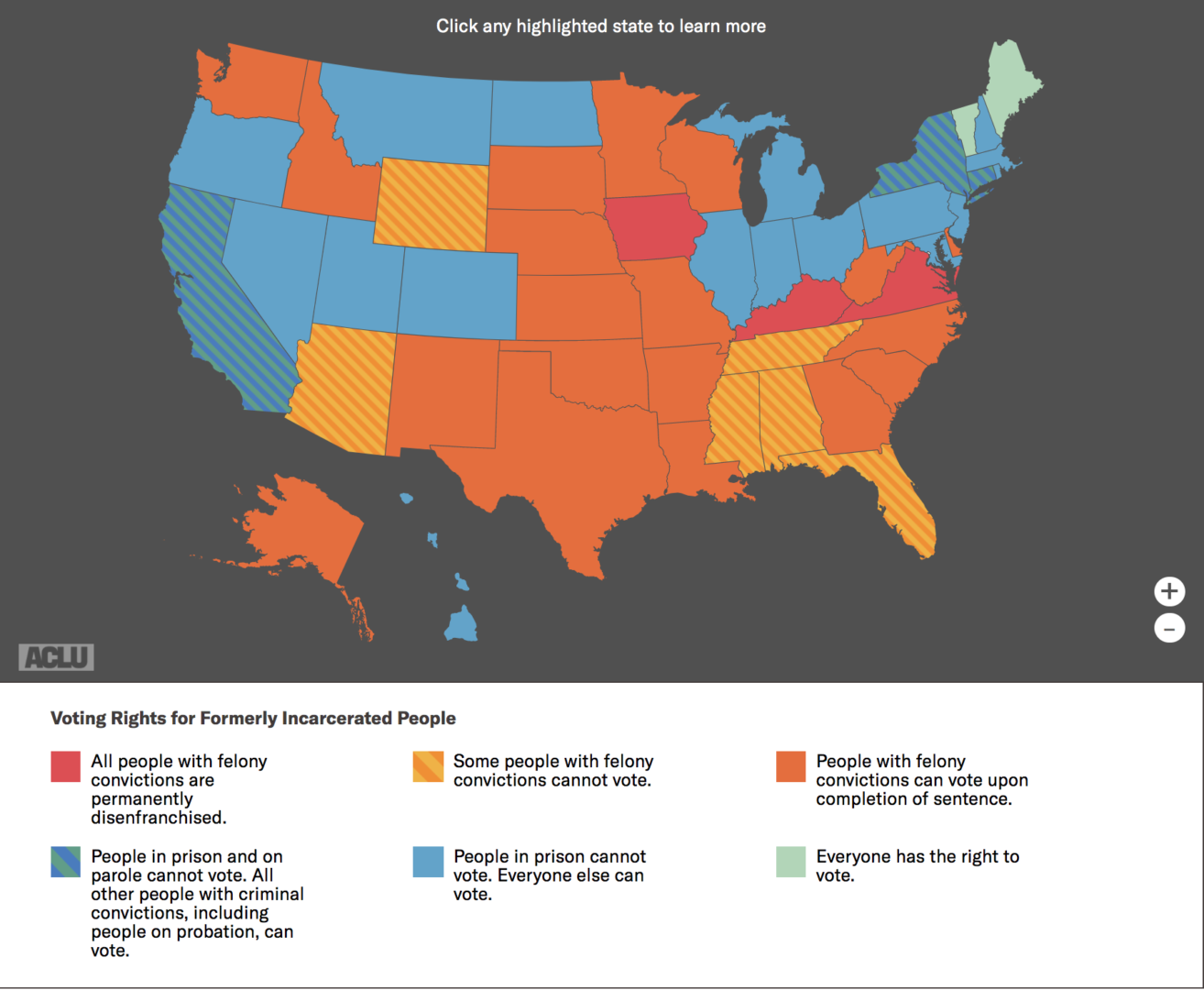

The only people not qualified to vote are currently-incarcerated felons (although they are allowed in Washington, D.C., Vermont and Maine). Those convicted of misdemeanors or infractions can vote in many states, except for the few that bar all inmates from voting.

Voting from jail is a massive youth issue. As of Oct. 31, 27,491 people under 31 are incarcerated in America. While this age group may seem too small to significantly influence national elections, young people voting in prison and recently-released youth carry a great deal of power in the political process.

A major problem when addressing young incarcerated people is juvenile detention. Although young people in America cannot vote until they are 18 years old, the critical knowledge of civic processes they need is taught during formative middle school and high school years. This education is almost never available in youth prisons or detention centers.

In addition, youths entering the system are often more disenfranchised than most other young Americans. A report from the Center on Education, Disability and Juvenile Justice states, “The majority of youth enter correctional facilities with a broad range of intense educational, mental health, medical and social needs.” The same report also mentioned that many young incarcerated people have “experienced school failure.”

As previously mentioned, education is a huge driving force in voting. The resources for historically-disenfranchised youth in juvenile detention (who are there most often for minor crimes, with the top offenses being theft, vandalism and alcohol possession or consumption) cannot compare to the civic education already lacking in the American school system.

Most young people do not historically vote because they lack education on how to vote, they have not formed habits, or have more “opportunity cost” than older Americans. Juvenile detention worsens these elements, where “approximately 50,000 youth are incarcerated” every day.

Even if incarcerated juveniles are released when they turn 18, many leave with disproportionate education. This disproportionately affects young people of color, since they are incarcerated and convicted at higher levels than white Americans.

Although many are eligible to vote, most don’t. The Sentencing Project says this happens because “jail administrators often lack knowledge about voting laws, and bureaucratic obstacles to establishing a voting process within institutions contribute significantly to limited voter participation.” Even if incarcerated people were aware of their voting rights, it is difficult to request and submit an absentee ballot without regular access to a computer or a phone for contacting a local Board of Elections.

Numerous local grassroots organizations take up the torch of spreading civic education to prisons. One of the most well-known organizations is The Ordinary People Society, which has been working since 2003 to register incarcerated and formerly-incarcerated voters across the American South and help them return ballots to local election offices.

Some states have laws specifically set for civics education. Illinois’ Re-Entering Citizens Civics Education Act went into effect earlier this year and requires all state prisons to teach civics education and foster voting turnout with prisoners. Last year, Colorado and Arizona mandated state sheriffs “coordinate with county clerks to facilitate voting in jails” as well.

Young Military Populations: Voting from across the world

Voting in the United States as the average young person is already difficult enough––now try voting from across the world.

Young people make up the largest portion of people actively serving in the United States Armed Forces. With 595,129 people under 25 currently serving in the military, this group far surpasses any other age group.

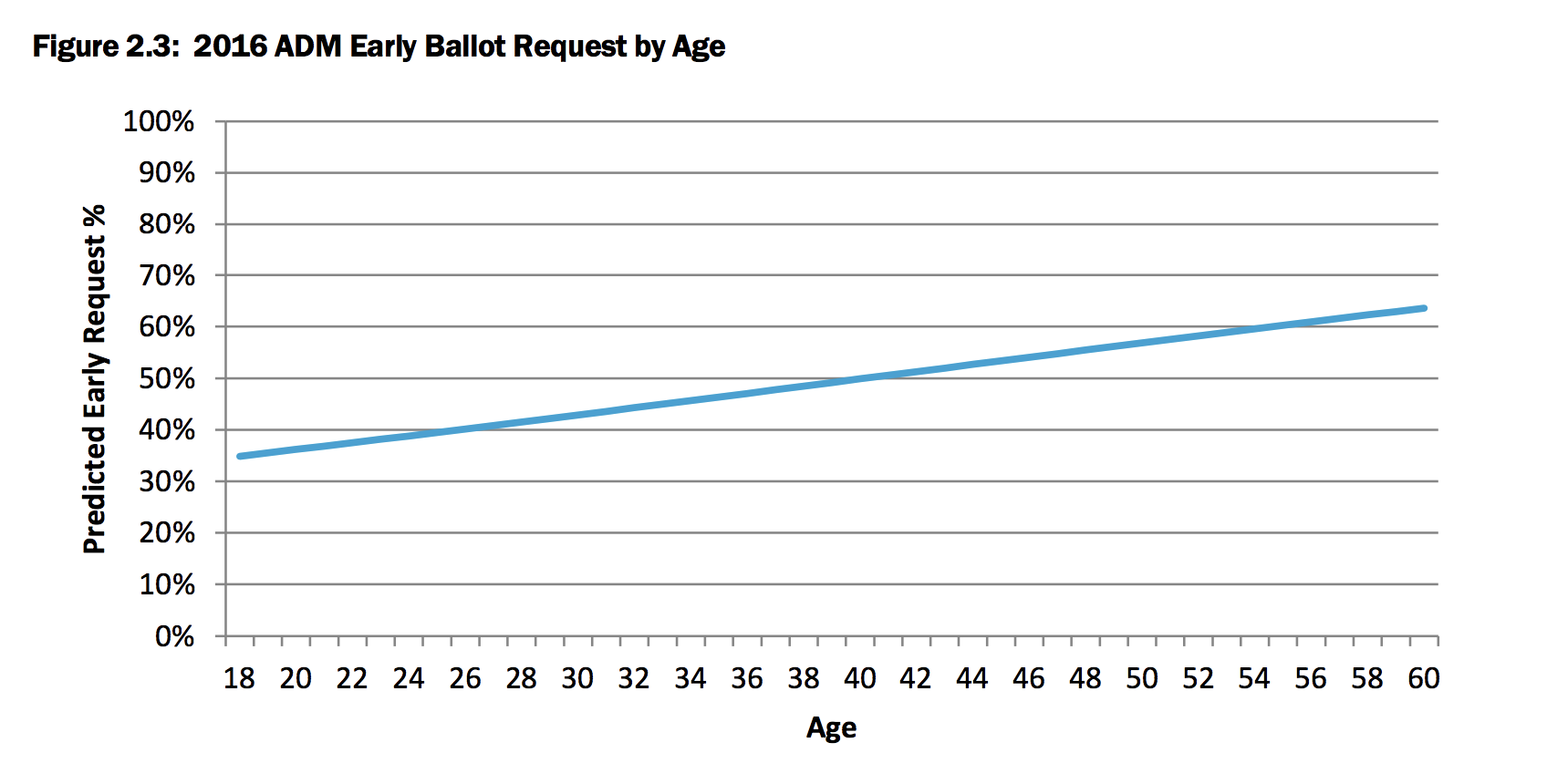

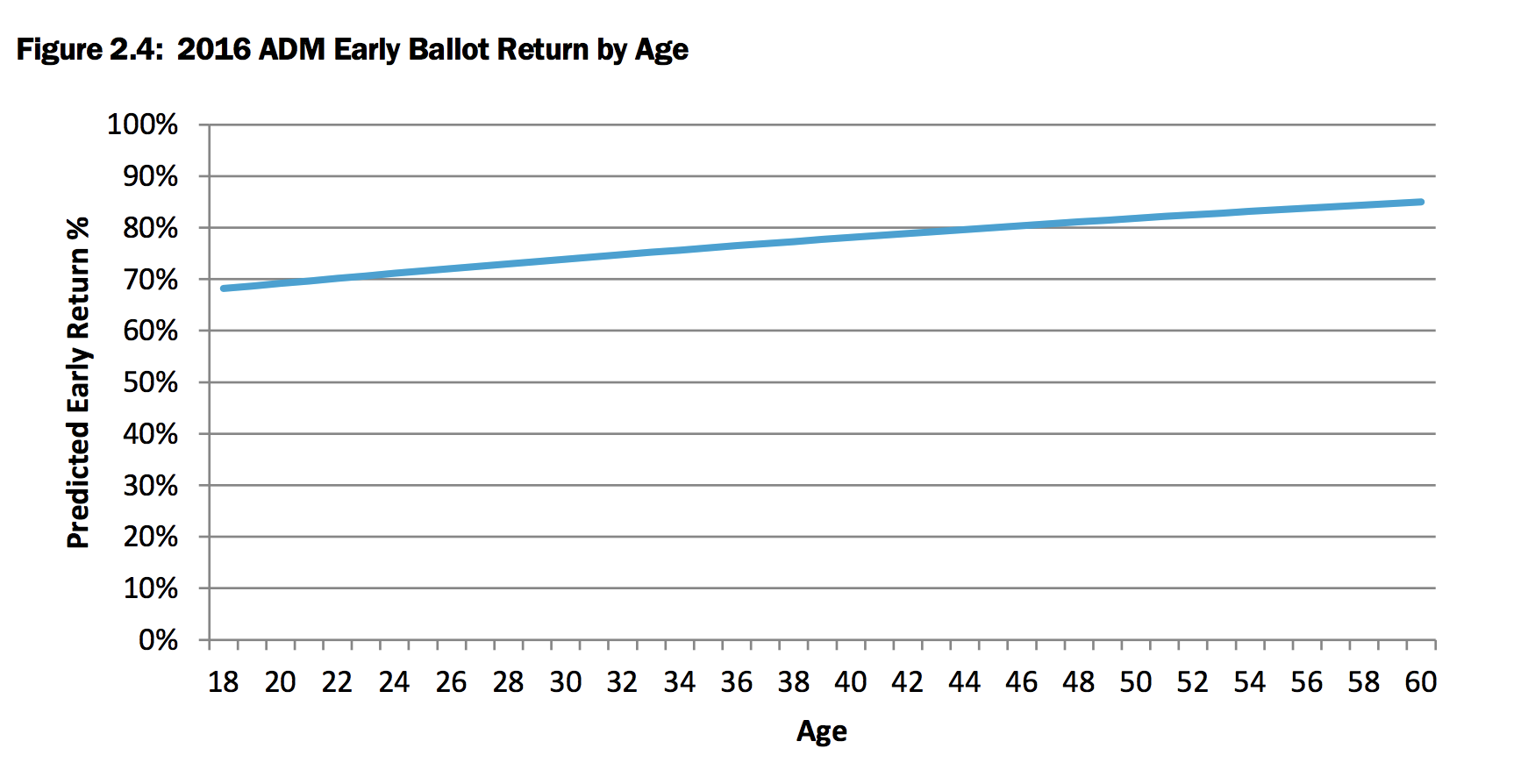

A comprehensive study from the Federal Voting Assistance Program stated, “respondents who were overseas, older, male and White were all significantly associated with a higher likelihood of returning a ballot early compared to other respondents.” Graphed data from the same report shows how voting ballot requests and return in the military is at its lowest with younger troops.

Brandon Anderson, a DU student who served in the Marines from 2007-2011, expressed that, although he had resources to learn about voting during his service, he had other reasons for not being fully engaged in voting. Anderson felt especially detached from America’s political processes when he was on active duty in the Middle East and Europe.

“You’re so damn busy [in active duty],” said Anderson. “We were always training and on the go. Whenever you had a free minute, you really just wanted to do what you wanted to do. With that being the context, voting wasn’t as important to us when we’ve been in the field for 30 days with no showers and now it’s like ‘Oh, it’s time to vote.’ No, I’m going to get a cheeseburger and a shower first.”

Anderson continued to say that after being in both training and on active duty for more than two years, he felt detached from current American politics.

“I don’t think I voted that year because a big part of it was I didn’t feel informed… and I didn’t feel like I was knowledgeable enough to vote,” said Anderson.

Even though he felt encouragement from the Marines and often heard about voting, the pressures of active duty, the lack of direct proximity to American issues and the lack of formal education on politics and policy in the military contributed to him not voting.

Children of immigrants and Dreamers

Another historically disenfranchised voting group is mixed-status young people, i.e., Dreamers (children who were born in the United States to immigrant parents). Although DACA recipients are able to access opportunities like getting a driver’s license or entering higher education, they cannot vote and are termed non-citizens until they receive green cards.

PEW Research Center reported that “two-thirds of DACA recipients are ages 25 or younger.” They are a sizable population across both traditionally “red” and “blue” states,” with the largest populations living in cities like Los Angeles, New York, Dallas, Houston and Chicago.

Dreamers have proven to be active in politics. They are not eligible to vote, but they live in America and care about its policies. Dreamers held key roles in both Bernie Sanders’ and Hillary Clinton’s campaigns in 2016, and the immigrant-led organization United We Dream has more than 400,000 members who work to rally for undocumented immigrant and DACA rights.

Politics is not limited to voting, as it includes activism and community organization as well. Dreamers play a huge role in this work. This is consistent with Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement’s study that reported, “youth of color (especially young Black women and young Latinas) were the most likely to be active in [political activist] movements.”

The questions of education

Huge numbers of young people are not being accurately represented in the voting process, and it all comes down to a lack of fundamental education. While incarcerated youths and young troops often need more education about voting, Dreamers frequently occupy key roles in educating others on issues and how to vote through grassroots organizations.

This begs multiple, hard-hitting questions: should civic education be mandatory in all American schools, prisons and military organizations? What type of funding is needed to accomplish this? Should people in these populations be voting if they feel disproportionately educated about the issues on the ballot and they are not physically present in the spaces they cast their ballots in?

Education is not an easy issue to tackle, and there is great debate regarding if people in these groups should be able to exercise civic rights. Is widespread representation or well-rounded education more important? If anything, these groups help Americans grapple with some hard-hitting questions about the country’s political process and what groups benefit more or less from it.