This article is part two of a six-part series detailing youth political subcultures and the role of youth political participation and activism in the past and present. By highlighting political activity at DU, this column seeks to find patterns in historical and present-day activism among youth populations. It hopes to shed light on how American youth populations view various political issues in different or similar ways from other youth voters and older generations.

On the other end of a Zoom call, Genesis Gordiano begins to cry. She tells the story of when her mother was deported back to Mexico spring break of her freshman year. While classmates posted pictures in Cancún or Cabo, Gordiano left her mother in Mexico for good and returned to school with immeasurable sorrow.

As a third-year DU student and Vice President of Latinx Student Alliance (LSA), Gordiano is one of many students of color on campus living with a DuBois-esque double consciousness. While she attends classes and works toward degrees in both psychology and sociology, she and fellow students of color carry marginalized identities, roles and burdens on and off campus.

Gordiano and Bríana Aguilar, DU’s LSA president, laugh about the rampant Hydro Flasks, trips to Paris and complaints from white students about “no avocado in the dining halls” at DU and other predominantly white institutions (PWIs)—but a layer of exhaustion coats their daily activities.

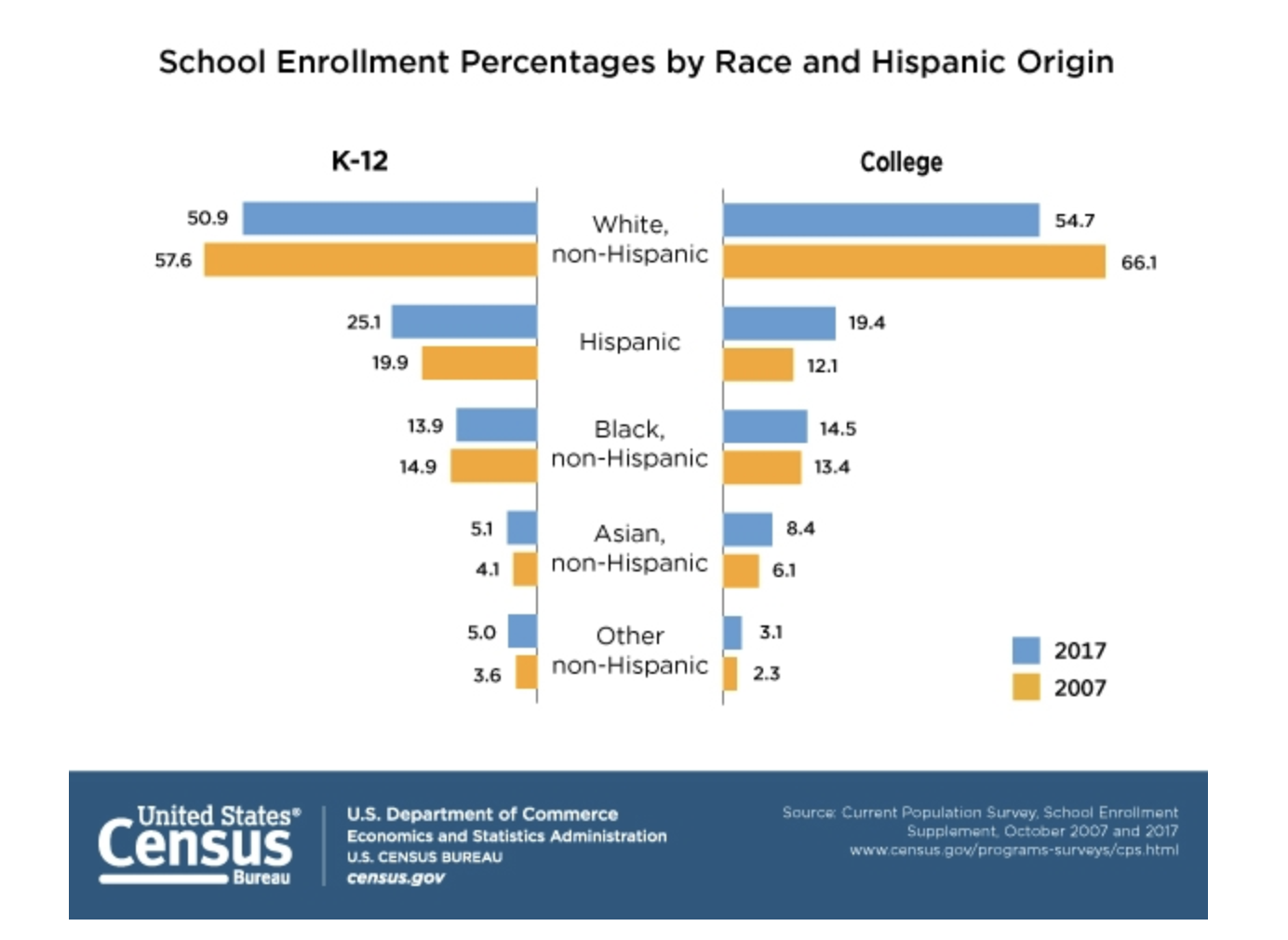

Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) make up around 25% of DU’s student population. This is closer to the national percentage at all American universities (29.6%) than in past years, but it still leaves something to be desired. As of 2017, white student college enrollment exceeds Black, Hispanic, Native American and Asian enrollment nationwide by more than 30%. Generally, BIPOCs in higher education face a greater risk of mental health issues and a more stressful college experience.

As young students of color, people like Gordiano and Aguilar hold a unique position in 2020’s political landscape. In the next installment in my column, “The Young and Restless,” this article explores how the political participation and leanings of these youth voters of color will influence the upcoming election and American politics in general. The interviewees defined politics broadly, including voting, raising political awareness and engaging in activism as political activity.

This article features interviews with the following student representatives from LSA, the Black Student Alliance (BSA) and the Native Student Alliance (NSA): Gordiano (LSA), Aguilar (LSA), Taylor Lucero (NSA Co-Chair), Nevaeh Garrison (BSA Vice President) and Matthew Solomon (BSA President).

Young voters of color and their role in politics

The decision to write a piece on young voters of color was strongly tied to data on the Millennials and Gen Z (as of 2020, Millennials range from ages 24-39, and Gen Z is all people 20 and younger. There is no real generational attribution for those born between 1997 and 2000).

Pew Research Center stated that “members of Gen Z are more racially and ethnically diverse than any previous generation,” only trumping Millennials, who previously held the record. This diversity “significantly contribute[s] to Millennials’ [and Gen Z’s] divergent political philosophies, social views, and policy preferences” from older generational politics, according to Stella Rouse’s and Ashley Ross’ book, “The Politics of Millennials.”

Generally, members of Gen Z are shaping up to be a more extreme form of Millennials. The two groups share similar left-leaning views on many political issues even among the Republicans in both generations.

64% of Millennials think “the government should do more to solve problems,” a slightly lower proportion than “GenZers” (70%). The two groups have approximately the same proportion of people (two-thirds of the generation) who believe “blacks are treated less fairly than whites” in America. Pew reported more Gen Z and Millennials plan to vote for the Democratic candidate than President Donald Trump in the upcoming November election.

Similar correlations exist on gun control, gender neutrality, climate change and immigration.

If Gen Z and Millennial voters cast their ballots in the upcoming general election, they can make up 37% of the American electorate. While age is not an outright indication of voting preferences, well-documented correlations indicate that young voters could make a large impact by likely supporting Democratic candidates in all levels of government.

The tendency for younger people to support Democratic candidates points to increasing political polarization among generational gaps, as well as socioeconomic and racial differences. DU Political Science professor Seth Masket spoke with The Clarion on how this polarization is currently at an extreme high in history.

“It used to be that parties cut across different social labels,” said Masket, who recently published a book called “Learning from Loss” about the Democratic party. “You had conservatives and liberals in the same party, you had black people and white people in the same party, you had poor people and rich people in the same party. Increasingly, parties are reinforcing those divisions instead of cutting across them. You have one party that is explicitly about wealthier white people outside of cities and another party which is the opposite. That makes it very hard for them to compromise on anything.”

This phenomenon has likely contributed to the surge of young American activism seen in recent years, especially from youth of color. In 2018, “youth of color (especially young Black women and young Latinas) were the most likely to be active in movements.” Studies indicate there is a strong presence of BIPOC-driven activism in 2020 as well. This vast and complex subculture can make a huge difference in American politics.

Youth of color as necessary activists

The risks of political participation are much higher for BIPOC youth than their white counterparts. Youth of color are more likely to experience violence and harassment for engaging in politics, far more concerned with surveillance from institutions and more cynical about current American politics.

Most of the interviewees for this article mentioned they and other young people of color fear violence as a result of their activism. Aguilar fears the upcoming election, haunted by stories of students of color on DU’s campus being egged by their white peers after the 2016 election. Garrison spoke of the “looming threat of violence from law enforcement.” Solomon worries a backlash similar to the Charlottesville white nationalist movement could happen at DU. Lucero spoke about the acts of discrimination and violence as well as continued “racism, oppression, microaggressions, and hate speech” that she and other Native students have experienced on and off campus.

These students express that their activism is necessary, despite the risks.

“We have to [be activists],” said Gordiano. “If we aren’t speaking up for ourselves, no one else is going to. If we want change, we can’t rely on the university to see injustices and discrimination against people of color and do something…we can only expect the university to want help or contact us when they need funding.”

Solomon stated that while he enjoys his ability to make his voice heard and stand against racial injustices, he doesn’t want his college years to be “a cat-and-mouse game” with the DU administration.

The other interviewees concurred with Gordiano’s and Solomon’s sentiments, saying they felt administration would shun inclusivity if it were not for activism from people of color.

While some students find activism to be a distinct BIPOC burden, others have used it as a way to find their voices.

“I find activism exhausting but in a good way,” said Lucero. “I always have to keep in mind that change doesn’t happen overnight and that it takes hard work for periods at a time. We may not always get the results or support we want, but that hasn’t stopped me from trying to make a difference.”

This activism from students of color at DU is analogous to nationwide historical and present-day movements. Across America, students have stood up for racial equality, DACA, funding for education and so much more.

In 2020, the pandemic has further mobilized youth of color who must “bear the brunt of the pandemic’s economic downturn while leading the charge in civic engagement.”

Combating misinformation and educating peers

The pandemic has publicized numerous hot-button political topics that have been shown to affect people of color more negatively than white people. This is true of climate change, healthcare and student loan debt, among other issues. In turn, young voters of color often have to take into consideration how their communities are implicated by the issues they consider promoting or supporting.

Student affinity organizations also reported how they can feel conflicted about choosing to align with one political party or ideology.

“We’ve taken part in the MLK parades and made our stance [in support of] Black Lives Matter because these are issues that are obviously really important to us,” said Solomon. “At the same time, the current climate puts students in a hard place when affinity groups take certain stances [on party affiliation]… If we say ‘Hey, we are more left-wing or more like this,’ it can make them [conservative Black students] feel as if they’re not welcomed or that their ideas are not as important.”

Assigning political stances to entire BIPOC communities has also become a standard currency in mainstream media. The interviewed students expressed frustration regarding the media’s reference to “the Black vote” or “the Latino vote.” They feel this dilutes their community’s various political opinions and filters them into a falsely monolithic voting group. These attitudes are heightened for young conservative voters of color.

This tendency to cluster minority groups together as one can also discourage people from doing their own political research.

“It’s wrong to assume everyone will vote a certain way because it might push someone who is not educated [to vote that way],” said Aguilar. “Personally, I know my abuelita might watch the news and say, ‘That’s how I’ll vote because that’s my community.’ It spreads misinformation, and it doesn’t give people a sense of agency or the opportunity to make up their minds.”

Aguliar continued to say that grouping the Latinx community together reinforces stereotypes, a major one being that all Latinx people support Catholicism, and, in turn, pro-life political action. The interviewees expressed the need for mainstream media to clarify that, while statistics may point to similar political beliefs across demographic groups, this does not define the entire community. This issue is distinct for communities of color, since the media does not typically discuss “the white vote.”

To combat misinformation and promote self-education, DU’s affinity groups actively promote awareness on voting and political topics. LSA hosted a “how-to-vote event” last Wednesday. BSA hosted a “Know Your Rights” workshop last year that taught students their resources and rights in interactions with campus safety and the police. NSA has partnered with other affinity groups to support the student R.A.H.R. group and Black Lives Matter.

Tying to the past: A rich history of affinity group activism

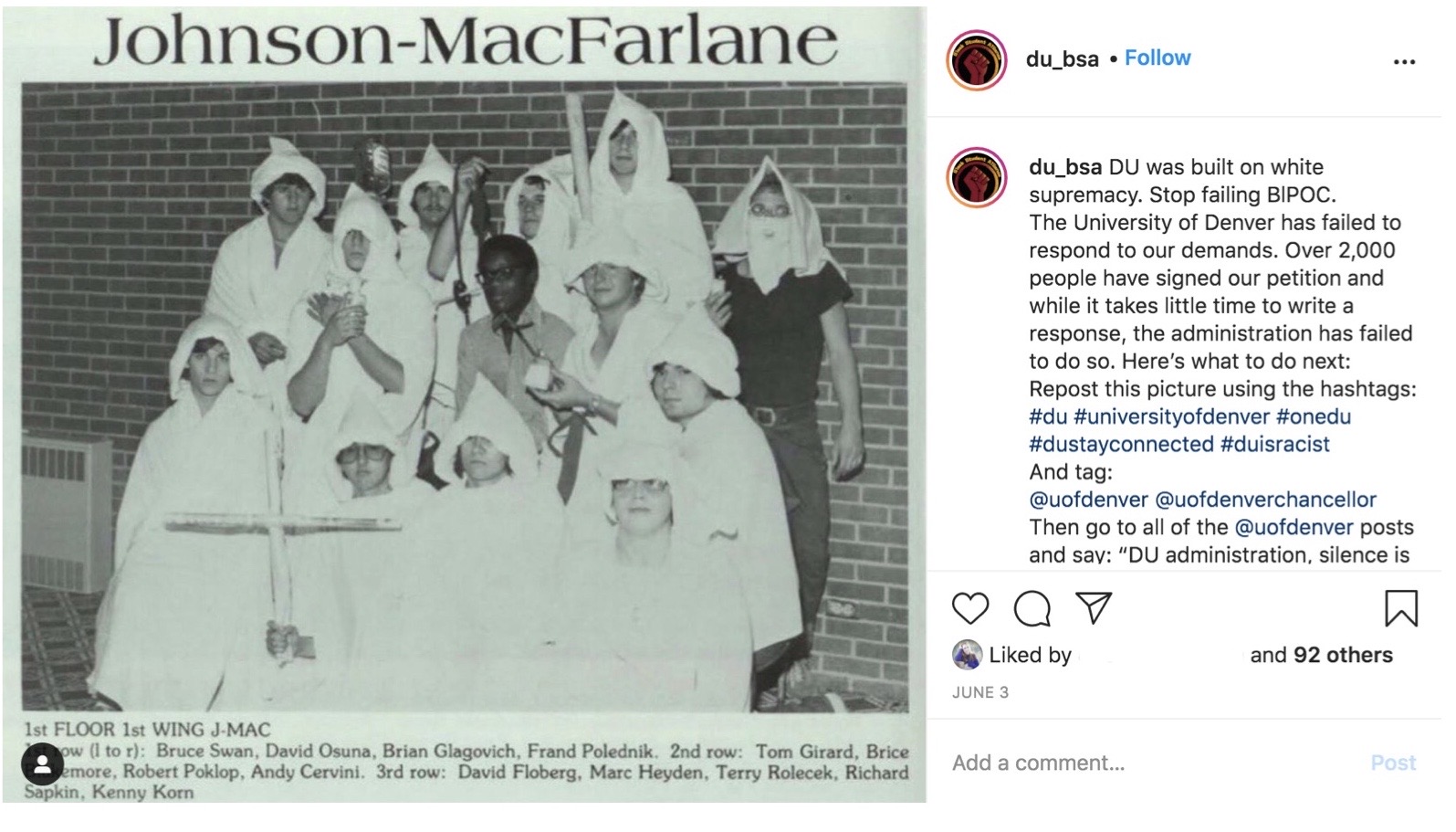

DU’s BSA, LSA and NSA are historically politically active organizations. In the past 15 years, most of the protests on campus have been organized by affinity organizations and marginalized students Many of them revolve around DU’s negative history. Instagram accounts like RememberX – an organization also founded by students of color – actively make DU’s history public through archival research and help propel student movements.

In 2017, Black students organized the Take a Knee “blackout” protest on Driscoll Bridge “in solidarity with Colin Kaepernick.” They also held a “die-in” on the anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination in the Anderson Academic Commons (students laid in silence on the floor of the library for 16 minutes in memory of Laquan McDonald, who was shot by police 16 times in 2014).

In 2018, LSA sponsored a comprehensive affinity-group protest on Driscoll green under the rallying cry, “Raza Unida.” The phrase means “united race” and is an allusion to La Raza Unida Chicano political party in the 1970s. This protest was in response to an email sent out to various DU community members. It included remarks that described groups as “dirty Syrian refugees” and “caravans of filthy Latinos.”

NSA has spearheaded the ongoing movement to get rid of DU’s Pioneer moniker, a demand highlighted in the NSA-led Instagram page Decolonize DU. The movement protests the word’s association with the historical pioneers who murdered Indigenous people. One of these most notorious pioneers was Daniel Boone, an American explorer who served as DU’s unofficial mascot for decades until DU prohibited his imagery in 2018. DU stands on the site of the Sand Creek Massacre, an event in which DU’s founder John Evans took part.

NSA has organized individual protests within its ongoing movements. In 2013, three NSA members protested a DU Harlem Shake video that featured Boone. The organization coordinated a “No More Pios” protest in 2018 during which NSA and allies protested at a DU Hockey game. In 2016, NSA hosted a protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and DU’s hosting of the Pipeline Leadership Conference. In addition, NSA continually calls attention to and participates in activism surrounding Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

Now, DU students still carry on these necessary activist roles. However, movements led by white students have historically received more support from the DU administration and community than movements led by students of color. Garrison specifically highlighted wecandubetter, a movement that calls attention to sexual assault and gender-based violence at DU.

“wecandubetter got a much more timely response by administration [than movements from students of color] and a much bigger turnout by people on campus, and now they’re a national organization,” said Garrison. “Then, you have something like R.A.H.R. being done and see a much smaller turnout and the threat of big punishment by administration.”

She continued to state that fighting for issues of marginalized communities as a person of color is to “keep getting arrows in your back.”

Although several protests have defied this trend, generally movements organized by BIPOC students receive a high turnout when they directly affect white interests. The NSA-organized DAPL protest was one of the most attended in DU’s history, but its white turnout was in large part due to it being a climate issue. Lucero mentioned that while the protest was successful, NSA’s letter to the DU Board of Trustees about how fossil fuels disproportionately harm Indigenous communities and land did not receive a response.

Woodstock West (which protested the Vietnam War) and a 2007 protest against the Iraq War had historically large student attendance as well. Similar to the DAPL event, these protests arguably received more support since the issues converged with white students’ interests.

An outlier in this pattern is the largely white student-led group Divest DU, which was founded in 2014 and still exists today. March of this year, Chancellor Haefner issued DU’s latest administration response to their demands. He choose to fall in line with his predecessors and not divest from fossil fuels.

Still, DU administration has arguably given this group more opportunities to sit at the table. Chancellor Chopp invited them to present at a Board of Trustees meeting in 2016 and shared the details of DU’s investments to the Faculty Senate.

Most recently, activism surfaced on campus with the R.A.H.R. protest on Sept. 29. As of publishing this article, the DU administration has not yet responded to the demands made.

Dissenting opinions: Young Black conservatives

Although activism can be a unifying force, it often falls sharply along partisan lines: what about young people of color who go against mainstream movements? Much of the Black community votes blue, and it can isolate young, Black conservatives.

A report from Ismail K. White and Chryl N. Laird, authors of “Steadfast Democrats,” noted this historic trend: “Since 1968, no Republican presidential candidate has received more than 13% of the African American vote and surveys of African Americans regularly show that upwards of 80% of African Americans self-identify as Democrats.”

However, in a 2019 episode of VICE network’s “Minority Reports,” correspondent Lee Adams detailed a growing countermovement against this trend.

“President Trump received more votes from Black voters than both Mitt Romney and John McCain. “…Much of the media seems to be dismissing the growth of the Black conservative movement and instead attacks their character and motives,” said Adams.

The episode explored the reasons why young Black Americans are leaving the Democratic party for conservative ideology. Some feel Democrats only care about Black people when it comes time to vote. Others think predominantly black urban areas, educational systems and businesses “have been destroyed” by the Democratic party. A third subgroup believes Democrats have “grown increasingly violent and obsessed with race.”

These ideologies have catalyzed the popularity of Candace Owens and her Blexit movement (which stands for the “Black exit” from the Democratic party) among young “closeted black conservatives” in America.

In the VICE episode, young Black conservatives spoke of the backlash they face from those who believe they are “being used by Republicans.”. They felt pressure to act according to longstanding stereotypes.

“We see people like Candace Owens who say they’re free thinkers and that Black people don’t all think the same. However, at the same time, they promote white supremacist talking points,” said Garrison. “It’s really frustrating to be reduced down to your skin color and how you’re supposed to vote, while there are people in your community that look like you and are advocating against your best interests.”

Garrison explained that it is difficult to critique right-wing “freethinkers” and influencers like Owens and Kanye West “because the person is Black.” She said their messages hurt not only Black people but all people of color.

Garrison is one of many young people who do not feel that either party represents her community’s interests. A report from CIRCLE at Tufts University found that Black and Latinx youth are more likely than white youth to not associate with a political party.

As one young Black student from UNC Greeley said in “Minority Reports”: “both parties have never, to me, done anything for Black people.”

What issues matter?

It is difficult to make assumptions on a young person’s politics in 2020. However, many tend to gravitate towards issue-based voting.

Aguilar and Gordiano stated they believe the most important issues at stake in the upcoming 2020 election are: addressing system racism (especially in healthcare), protecting DACA, supporting undocumented immigrants, reforming the criminal justice system and more funding for education (in order to combat the school-to-prison pipeline prevalent in marginalized communities).

Solomon and Garrison offered similar thoughts. They prioritize establishing representation of people of color in all levels of government, reforming the police, criminal justice system and ICE, and combating systemic racism in education.

Lucero mentioned different issues than other interviewees: preserving and protecting Native land and sacred sites, promoting the federal task force that addresses Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), climate change, and improving funding and access to healthcare and education for the Native community.

Lucero also highlighted the presence of voter suppression and lack of political education in Native American communities. She brought up the low turnout in Native voters “due to a lack of knowledge of voting, language barriers, and having no access to voting at all.”

For those who live on Native American reservations, arranging transportation to a polling place is often difficult. According to Lucero, the “lack of residential addresses and no access to mail or digital participation” limits the extent to which the Native community can vote. These barriers has the potential to prevent the votes of “2.4 million eligible American Indian and Alaska Native voters living in the top 15 states with the highest populations of voting-age Natives” in the 2020 election.

The issues mentioned by student interviewees are consistent with national polls of young people of color, especially the sentiments to address the environment, racism and healthcare.

Young voters of color look to the election

“Students of color feel kind of hopeless right now,” said Aguilar regarding the Biden versus Trump match-up coming to an apex on Nov. 3. However, she has realized that, through her political engagement and steady activism on DU’s campus, her voice can impact something as large as a national election.

Her peers felt similarly. Aside from this activism being a necessary mission to improve the lives of current and future students of colors at DU, it has helped them unleash their voices and feel confident participating in politics beyond Driscoll Green.

Lucero, in a statement of optimism, made this clear: “It is definitely hard being in a space that wasn’t meant for us, but we are persevering every day as we work hard towards a better future for ourselves, our families, and our communities.”