This article is part four of a six-part series detailing youth political subcultures and the role of youth political participation and activism in the past and present. By highlighting political activity at DU, this column seeks to find patterns in historical and present-day activism among youth populations. It hopes to shed light on how American youth populations view various political issues in different or similar ways from other youth voters and older generations.

Here’s a riddle: I’m everyone’s favorite and least favorite activity, I inform people while I tell them lies, I’m addictive but repulsive—who am I?

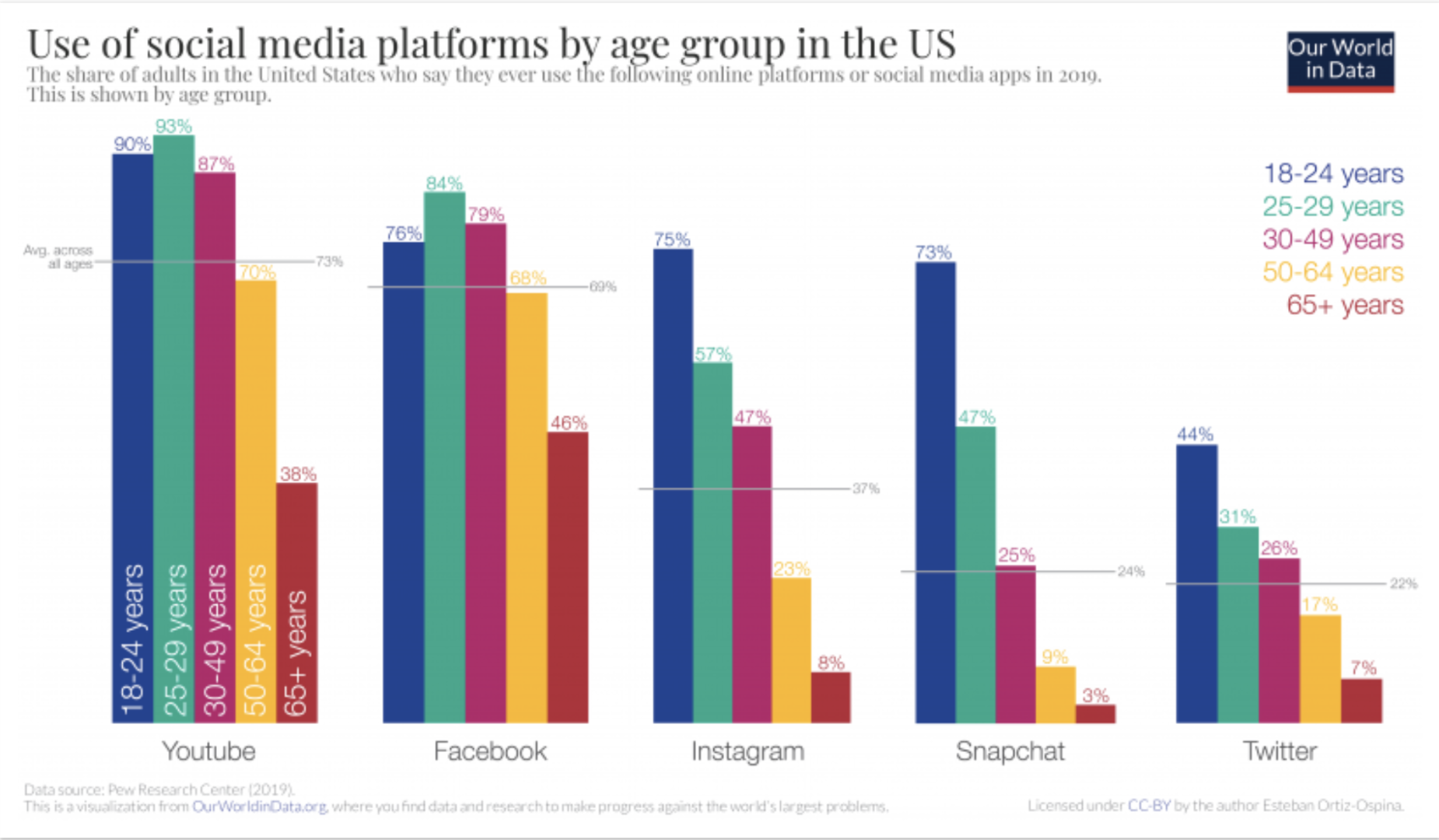

The answer is not “The Bachelorette.” But did you guess ‘social media?’ A simultaneous liar and truth-teller, social media is a necessary accompanist for young American’s lives in the 21st century. 90% of Americans in that age group use at least one social media site, and young people aged 18-29 use social media more than any other medium for news.

Social media plays an essential role in elections and youth politics (beyond informing people of flies encircling Mike Pence’s head). Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) reported that the majority of young people aged 18-24 found out about the 2018 midterm elections via “one of the four most commonly used social media platforms: Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter.” The report also found that “social media platforms are reaching youth not engaged by candidates and campaigns.” Social media may be a driving force behind the huge force of young people who have voted early in this upcoming election.

However, a Pew Research Center study revealed that those who primarily rely on social media for news “have lower political knowledge than most other groups” due to the amount of fake news and conspiracy theories that often infiltrate social media.

Does social media do more bad than good? Young people use it for both information and falsity, so the answer is a perpetual toss-up.

Trendy politics: the rise of slacktivism

Since the murder of George Floyd this summer, social media activism has surged on previously non-political platforms like Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat.

This activity largely modeled “slacktivism,” a term describing simple-minded internet advocacy. Slacktivist activities are often viewed as “performative activism,” in which people simply repost socio-political messages in order to appear “woke” and feel good about themselves.

Social justice became unusually “trendy” and manifested in various iterations with racial justice, global humanitarian crises and, now, voting. Although data from 2018 revealed “less than 10 percent of teenagers in the United States said they post about their political beliefs on social media,” Black Lives Matter changed that narrative significantly.

Although widespread slacktivism proved useful for mobilizing people to donate to social causes, one Pew study reported 71% of Americans believe social media is actually dangerous to activism. They believe re-posting information merely gives the illusion of actively working against injustice. Only 4 in 10 people read stories before sharing them on social media.

This begs the question: how much of political social media from youth is genuine, and how much only appears genuine?

Despite this, another study from Pew stated 69% of Americans believe social media is useful for political mobilization like reaching out to or Tweeting at Congressional representatives. In June, young people’s coordinated use of TikTok to reserve massive sections at a Tulsa Trump rally and protest against the president constructed a bridge from social media to reality.

A CIRCLE study from 2018 affirmed this online-to-offline activity, stating that “young people who engage in political activity online are also more likely to engage in-person.”

Localizing: Social media at DU

This political social media participation is present at DU. As detailed in previous installments of this column, DU students are no strangers to political activism and advocacy. Recently, students have evolved into political social media aficionados.

Perhaps no student has perfected this more than third-year Grace Wankleman. As a devout activist, Wankleman is constantly juggling multiple projects: she co-founded wecandubetter and the nationwide Do Better campaign, serves on the Undergraduate Student Government and acts as a member of the Feminist Majority Foundation.

Wankleman’s most recent project is a DU-based Instagram account (@no115unidenver) that advocates for students to vote “no” on Proposition 115, which would make abortions after 22 weeks illegal in Colorado.

Through all her activism, Wankleman has employed social media as a close compatriot.

“It [social media] is an accessible tool that elevates the voices of those who have often been far too ignored,” said Wankleman. “With my work in opposition to Proposition 115, I have witnessed the importance of sharing commonly-overlooked stories. Social media helps share these crucial narratives effectively and provides an incredible opportunity to individually engage with individuals.”

Historically, activism at DU has not revolved around specific propositions, but this narrowly-tailored account serves as another example of America’s growing youth political activism; its use of multiple virtual and in-person mediums to translate a political message represents how passionate young activists are about getting a message across and supports a CIRCLE study finding that youth who engage in both online and offline activism are more likely to vote.

Even more uncommon is a dueling account; @yes115du advocates for passing Proposition 115.

“Our team has not had much interaction with that page [@no115unidenver] because they blocked us without cause,” said Caitlyn Achilles, one of the leaders of @yes115du. “Their page was started before us, [and] this page was created for the purpose of countering them.”

The 10-member team behind the pro-life account also participates in in-person activism. Known as “Students for Life” on campus, the group frequently tables or hosts events on pro-life causes, and they volunteer in Denver for pregnancy centers. According to Achilles, members are “heavily involved” with “help[ing] pregnant women on campus get the resources they need to courageously support the life of their child.”

Wankleman views Achilles’ page as problematic and expressed concern for the account’s messages. She specifically mentioned one post that reads: “Everyone who supported slavery was free. Everyone who supports abortion has already been born.”

“To equate slavery and abortion is simply abhorrent in my opinion and demonstrates the deeply entrenched problems present in this campaign’s messaging,” said Wankleman.

The misinformation crisis

Although DU students’ social media activist accounts are largely helpful and representative of larger student groups, social media on a nationwide scale can often be harmful—especially with misinformation during election seasons.

Misinformation can take many forms and be propagated by all ages. Robots aggressively comment and like certain politicians’ posts. “Bad actors” photoshop images or create deep fake videos. Meticulously-organized swarms of party-aligned supporters flood social posts or channels, commenting and reposting support for a candidate and liking partisan posts.

A recent study from the University of Colorado Boulder affirmed that there is not an age limit for who shares the most political misinformation; rather, anyone who identified as “extremely liberal” or “extremely conservative” did this bidding.

One study on WhatsApp found that young people “are more likely to share content if it connects with their interests, regardless of its truthfulness” and “the appearance of newsworthy information ensures that, regardless of the nature of the content, this information is more likely to be shared among young people.”

Misinformation can victimize young people. The New York Times reported that people aged 18-24 are more likely to believe false information about the coronavirus.

Dr. Derigan Silver, an associate professor of media law at DU, spoke about how private companies like Twitter and Facebook attempt to regulate misinformation.

“What it really boils down to is that the largest public sphere in the world is controlled not by the government, but private corporations,” said Silver.

Now, most social platforms rely on flagging content via users, algorithms and human employees to monitor misinformation following the backlash against Facebook for its role in the 2016 election’s misinformation (the platform was criticized for not monitoring and policing Russian interference, data mining and false political information). Enough flagging can lead to filters that cover posts and warn audiences of false or misleading content.

Most social platforms have implemented these tactics. However, every private media company approaches misinformation differently and uses different ethos to decide whether to take a post down or not.

“The way that Twitter approaches things is very different from the way that Facebook approaches things,” said Silver. “Facebook has tried to take a more hands-off approach and say, ‘Hey, who are we to say what is good and what is bad?’ They’ve gotten a lot of grief over that, for [allowing] conspiracy theories and hatred. But, the big one [found] on Facebook is false political information that is incorrect and designed to change the way people believe, act and vote.”

Among the headache of issues surrounding social media, there exists a central dilemma. Misinformation should be stopped, but how can it be done in a way that doesn’t overreach on people’s freedom of speech and first amendment rights?

Looking to the future

In addition to the misinformation dilemma, social media often encourages people to not change their minds.

“I mostly see political material that aligns with my personal political beliefs on my social media,” said Wankleman. “Though I am undoubtedly a fan of the many benefits it [social media] can offer, it is crucial to examine the negative effects, especially in a political climate like ours.”

For Wankleman and everyone else, social media algorithms tailor information based on posts that users like or look at often. This effectively creates an echo chamber and reaffirms individual confirmation biases. In this sense, social media merely exemplify trends already happening rather than serving as the sole creator of extreme political polarization.

Thus, with the bad actors, misinformation and data mining present, will it ever be possible to have free and fair elections ever again? According to Silver, we need not think so dismally.

“People have been having [this conversation] since the printing press,” said Silver. “New media always democratizes information. It takes the group of people who can control information and expands it.”

While this is both a good and bad thing, young people will undoubtedly be looking to social media, a simultaneously valuable and catastrophic tool, for furthering political causes in the 2020 election and in the future.