This article is the part three of a six-part series detailing youth political subcultures and the role of youth political participation and activism in the past and present. By highlighting political activity at DU, this column seeks to find patterns in historical and present-day activism among youth populations. It hopes to shed light on how American youth populations view various political issues in different or similar ways from other youth voters and older generations.

In an episode of Netflix’s news comedy show “Patriot Act,” comedian Hasan Minhaj presents an unusual metaphor: Democrats are Denny’s, and Republicans are Chipotle. After chuckling at his own humorous comparison of political parties and chain restaurants, Minhaj dives deeper into what he meant.

“Democrats are like Denny’s,” said Minhaj. “They’ll serve anyone any meal at any time…You want voting rights, renewable energy, education, drone strikes, pot roast, they got it, everything is in there… Republicans are way more narrow. Their menu is like Chipotle. They got a few key items: immigration, abortion, guns, God. You have to stick to the menu, or you’re out… Democrats can’t afford for people to leave, so they keep expanding the menu.”

In this uncannily-apt metaphor, Minhaj describes the driving reason why many young people are so unsatisfied with politics: neither party is operating effectively. While Democrats take on too much, Republicans are too limited. This search for a happy medium has the power to influence major elections through an alternative option: third parties.

Third parties are alternative parties that possess different ideologies than Republicans and Democrats. Organizations like the Green Party and the Libertarian Party represent some of the larger third parties in recent years. Yet, even though there are 19 alternative/unaffiliated parties with candidates on Colorado’s ballot this year, virtually none of them will impact the stronghold of America’s two-party system.

Why is that? There is a common debate surrounding third-party politics. Some Americans believe that they should be able to vote their conscience and for any candidate, including independents. Others believe voting third party is a wasted vote, drawing votes from a Republican or Democratic candidate who could benefit the majority of Americans.

In 2020, the latter’s logic is taking charge. Although there is a major split between progressives and moderates in the Democratic party, even the most progressive of the Democrats are rallying behind the moderate Joe Biden to defeat the highly-polarizing President Trump. This phenomenon is aptly presented in the headline of a Wall Street Journal article: “The Force Unifying Democrats? It’s Donald Trump.”

An anonymous DU student also voiced their opinion on this, saying they “find it useless” to vote third party.

“Even though we have other parties, none are large enough to offset the power of the Republicans or Democrats,” said the student. “I think it’s useless to vote for the other candidates. [People should] at least try to vote for a candidate who stands a higher chance of winning and will align with some of your ideologies.”

Elizabeth Warren, former Democratic presidential candidate and Massachusetts senator, called upon her fellow progressives to reunite the party in an interview with progressive celebrity politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC): “We can’t afford to beat Donald Trump by a little bit; we’ve gotta beat Donald Trump by a huge amount. And that’s how we reassert the strength of our democracy.”

Warren and AOC are just two of many progressive politicians, including Bernie Sanders, who do not agree with Biden’s more moderate policies but have come out in support of his potential presidency. As a result of this drive to vote President Trump out of office, Democratic politicians and left-leaning Americans have organized a coordinated effort to strongly discourage third-party voting and save those votes for Biden.

Considering this, third-party voters and disenchanted Democrats and Republicans may be some of the most impactful and deciding votes leading up to the Trump v. Biden matchup in three weeks. Yet, no matter where these votes go, one thing is clear: no, it is not a good idea to vote for Kanye West.

Background research: dissatisfaction with Democrats and Republicans

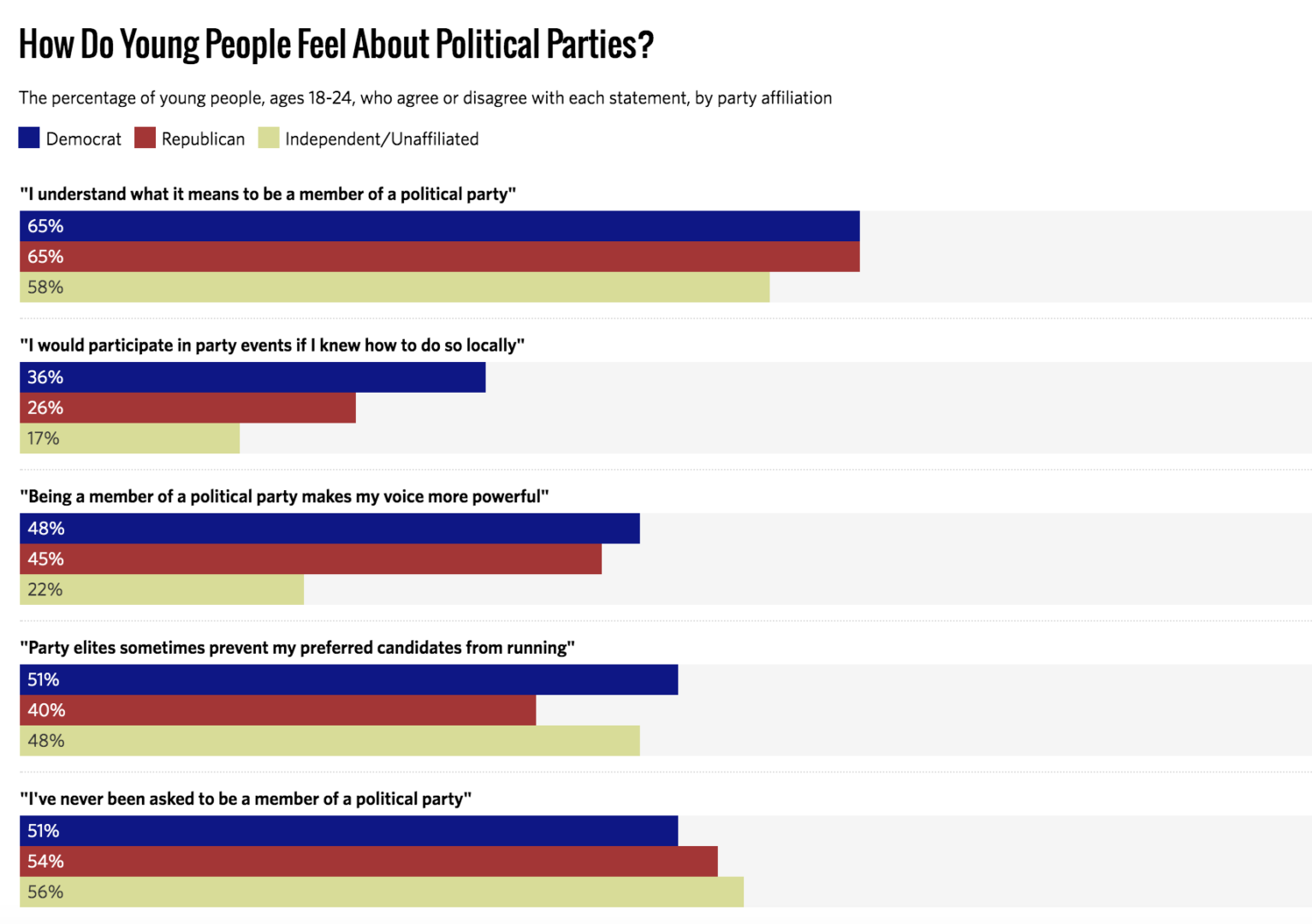

As detailed in the last installment of this column, young people (especially young people of color) are less likely than older adults to identify themselves with a single political party. They are poised to seek out candidates and policies outside of Democrats and Republicans.

According to a study by PEW Research Center, “independents are younger and more likely to be male than partisans.” Another 2018 study from Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) revealed that “only 56% of young people, ages 18-24, choose to affiliate with the Democratic or Republican parties.”

CIRCLE speculates the growing number of American independents could be a result of the polarization in the Supreme Court and Congress and “the behavior of both parties’ establishments during their respective 2016 presidential primaries.” The same report noted that many young people feel neither the Republican nor Democratic establishments are effective or accurately represent young people specifically.

This is not a new concept: a 1992 issue of the Clarion described even then, 47% of newly registered voters at DU chose to be unaffiliated, which was “symbolic of a current national trend.”

All of these statistics largely contribute to the idea that generations of young people—Millennials and Gen Z—are far more politically progressive than older generations. They politically align with each other in many ways, tending to favor liberal policies in regard to climate change, immigration, LGBTQ+ issues and other issues. This is true even among Republican-leaning youth.

Young people tend to support candidates who didn’t make the general election presidential ticket. In 2016, left-leaning young people showed overwhelming support for Bernie Sanders and were largely unsatisfied with Hillary Clinton. Similarly, young Republicans also showed less support of President Trump than older Republicans in that election.

In 2020, young progressive voters have vocalized their distaste of Biden as the nominee, paralleling the 2016 Democrats’ choice of the more moderate Clinton. One report from USA Today revealed that “nearly 1 in 4 Sanders supporters (22%) said they would vote for a third-party candidate, vote for President Donald Trump, not vote in November or were undecided about who to vote for.”

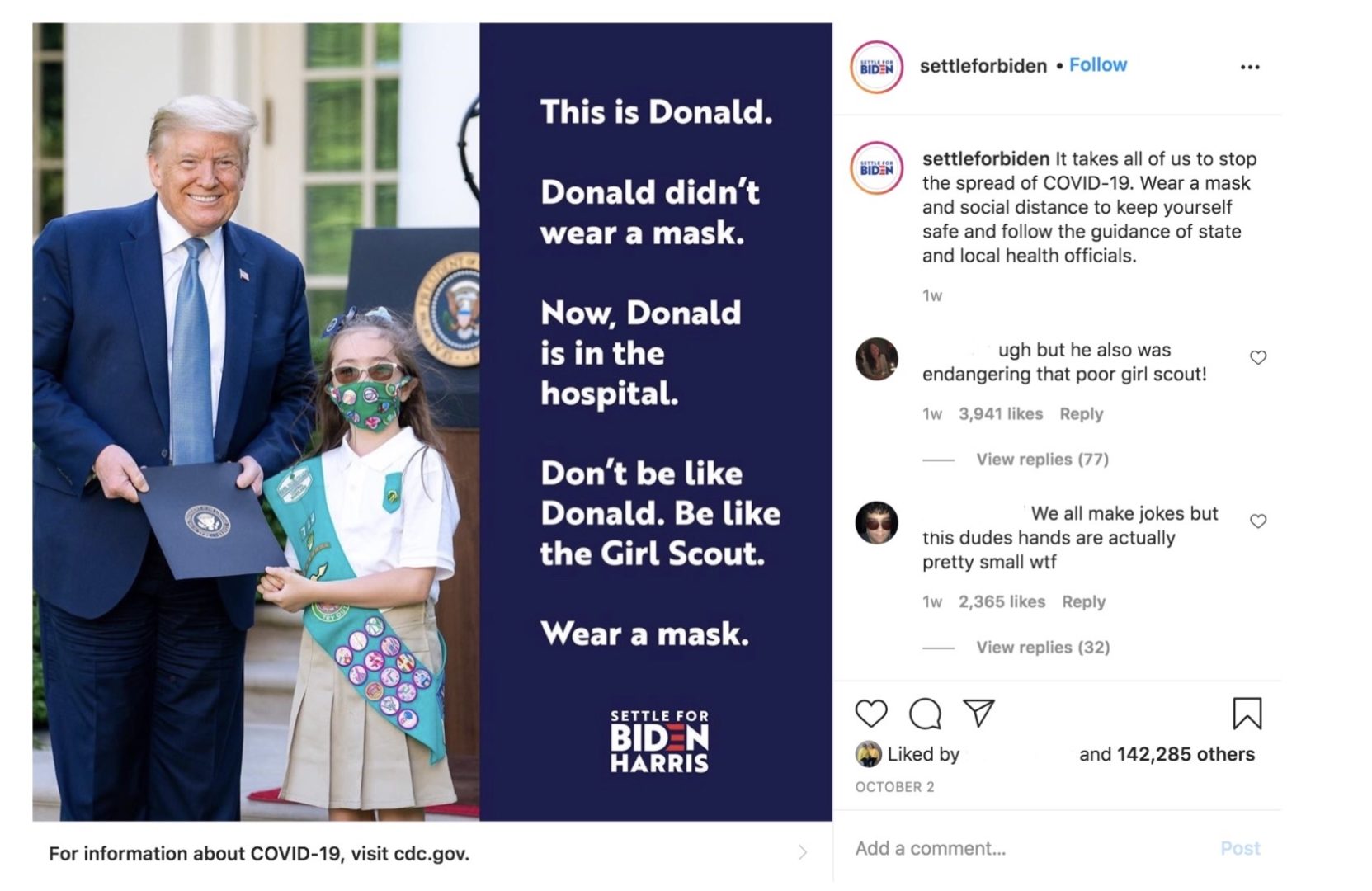

However, left-leaning young people are following suit of progressive Congresspeople and fighting to elect Biden. The Instagram account @settleforbiden has gained 258,000 followers under a familiar description: “Okay, fine. Biden 2020. We’re a youth-led group of ex-Sanders/Warren supporters working to make Trump a one-term president.”

On the other side of the aisle, similar coalitions among conservative-leaning youth have been slowly building against Trump. College Republicans for Biden, a Twitter account, has more than 3,000 followers, and a report from CNN illustrates how Gen Z conservatives are backing Biden, but would not have voted for a more progressive candidate like Sanders or Warren.

While this election has unified the split in the Democratic party, it has divided Trump and the Republican party. The pool of Republicans who voted for Trump in 2016 but grew unsatisfied with his presidency may choose to vote third party to avoid voting blue at all costs.

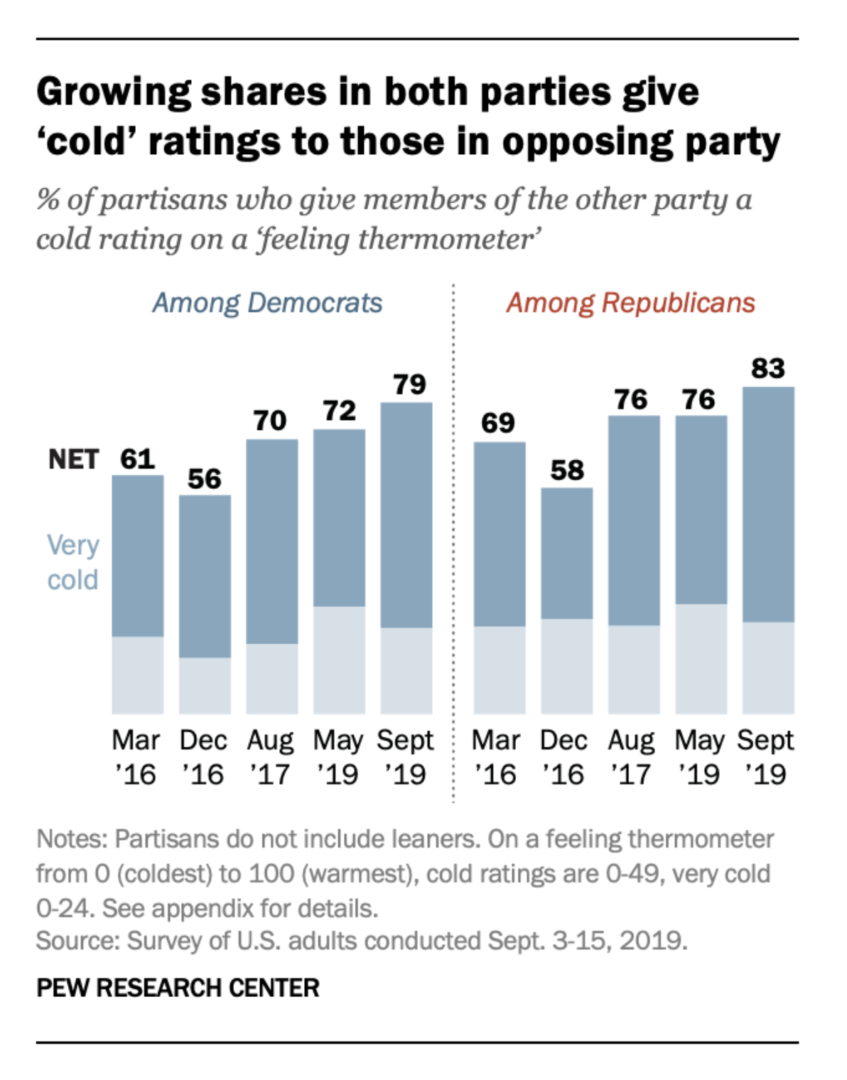

This hatred of the party on the other side of the aisle permeates America’s political system, and it is this “negative partisanship” that motivates people to vote third party even though candidates are almost never successful.

Tying to the past

However, there have been times when three people stood on a debate stage instead of just two. The cases of Ralph Nader and Ross Perot showcase two recent attempts where third-party candidates successfully shook up the election process.

Ralph Nader made a run for the presidency in 2000. Nader is a devoted political activist, and he is credited with helping the passage of the Whistleblower Protection Act, the Freedom of Information Act, and the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts among others. His giant public presence made him a “pop-culture star,” as he appeared as a host on shows like Saturday Night Live and Sesame Street.

Though he toyed with presidential candidacy in 1972, Nader did not make an official run for office until 2000. While Nader was a proportionately successful third-party candidate (he received 2.74% of the popular vote), the same negative attitudes towards third-party candidates plagued Nader. Similar to the way people said Gary Johnson took away votes from Clinton in 2016, many left-leaning voters expressed remorse for Nader and how he took away votes from Gore in the razor-thin 2000 election.

Nader also ran as an independent in 2004 and 2008 but did not succeed in making as big a mark as he did in 2000. In 2004, DU student Jon Burek employed this same logic attack against Nader’s 2004 run, stating that, if Nader really wanted to make a change, “he should [have] run to be a Congressman or a Governor.”

Perot also successfully ran as an independent candidate in the 1992 presidential election. Although Perot was a billionaire businessman, he became increasingly displeased with American politics and wanted to reform the system due to what he believed was poor American action in returning prisoners-of-war from the Vietnam War. He also opposed the Gulf War and NAFTA.

In 1992, he used unconventional election tactics, like having an “electronic town hall” and running popular “half-hour infomercials about himself and his ideas” on TV. Perot’s use of popular media arguably laid the groundwork for other candidates to also use technology as a campaign strategy. It established him as a powerful third-party force. Perot had supporters from all political backgrounds, but he drew from a strong middle-class base.

Perot won 19% (20 million votes) of the nation’s popular vote in 1992, a number unprecedented since Theodore Roosevelt and his Bull Moose Party. He ran again in 1996 but did not see the same widespread support as the previous election. As noted in a 1992 issue of The Clarion, Perot made history by “having at one time been more popular than either of the major party candidates.”

The Clarion has repeatedly publicized students’ political attitudes toward third-party voting. One piece from former student Caitlan Gannam made a plea to the DU community to not vote third party in the 2016 election. Gannam stated that, while neither Clinton nor Trump are “palatable nominees” to students, “voting third party will help [Trump] him win this election” and would be more detrimental to them than Clinton.

Another student, Paul Timmerman, stated in 2004 that America’s lack of third-party representation is problematic. He argued that encouraging people to vote for only Democratic or Republican candidates “rests on a prime fallacy, namely: in order to advocate change, one must not change oneself.”

Timmerman’s thoughts are shared by many Americans, evident by how Perot and Nader were able to carry substantial portions of the nation’s popular vote. However, today’s extreme political party polarization causes many people to vote third party for different reasons: rather than voting for what candidate they believe is best, Americans simply vote for what they believe is “the lesser of two evils,” as seen in 2016. In 2020, this same divide between parties caused a sharp reversal in voting patterns, encouraging people to vote for either Trump or Biden and no one else.

Reforming elections

Since so many people are dissatisfied with both major political parties, why can’t we just reform the system? If John Adams said that “a division of the republic into two great parties… is to be dreaded as the greatest political evil,” then why are we still operating in a two-party system?

Seth Masket, a DU political science professor, has conducted extensive research on this topic and on alternative political parties throughout American history. He details this research in his 2016 book, “The Inevitable Party.”

“A lot of the focus of the book was on how efforts to get rid of parties tend not to work, and that parties are actually a natural and normal occurrence in a democracy,” said Masket. “They’re actually healthy in a lot of ways, but the attempt to get rid of them often makes things worse. It makes politics more confusing, harder for people to follow [and it can] sometimes make it even more corrupt.”

However, while attempts to reform parties may not have proven successful, many young people support reforming elections.

A study from PEW reported that “women and younger adults are more likely than men or older adults to support amending the Constitution, so the candidate who receives the most votes wins the presidency.” This would mean abolishing the electoral college system.

“I think it[the electoral college] is outdated… The fact that states with less than a million people have as equal a say as states with millions is a little skewed in my opinion,” voiced an anonymous DU student.

An op-ed from a Yale student in the Hartford Courant and a report from the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics both reported that young voters also feel inclined to ranked-choice voting.

Ranked-choice voting is where voters rank their preferred candidates from highest to lowest preference instead of choosing one single candidate. If no one candidate receives more than 50% of the votes after this initial process, the “candidate who did the worst is eliminated, and that candidate’s voters’ ballots are redistributed to their second-choice pick.” This process repeats until one candidate receives 50% of the vote.

Several individual cities have implemented this in local elections, but Maine became the first state to adopt this program in 2018. New York City followed suit the next year. The upcoming presidential election will be the first in which ranked-choice voting will be used in America.

Interviewed DU students also expressed their favor of ranked-choice voting.

“I don’t know if it[ranked-choice voting] is the end-all-be-all or the most ideal form of voting, but I think it would definitely be a step forward and I would get behind it,” said an anonymous DU student.

Organizationally speaking, studies have also shown that implementing same-day registration, pre-registration and automatic voter registration “substantially increase[s] youth turnout.” This is due to the fact that young people often do not vote due to confusion around voter registration deadlines and technicalities.

This research reveals that Americans should not be attempting to overthrow the two-party system; rather, the country should focus on reforming elections first.

Looking forward to the election

All of this boils down to an idea permeating social media and celebrity content geared towards young, liberal Americans: vote – and do not vote third-party—so that Trump does not win the presidency. It is a message heard from top political superstars and DU students alike.

If this consistent push not to vote third-party continues, the Gary Johnsons in this election will likely not receive the same support they have in the past. However, as years go on, it may soon be up to the American youth to decide if election reform should come in the near future and open up ways for non-partisan candidates.

Undecided, unaffiliated and independent voters are asking themselves the same difficult question this year: do I eat at Denny’s, Chipotle, or do I just make my own lunch?