October is ADHD Awareness Month. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) affects approximately 4.4% of adults in the United States, which is about 16.5 million people. The number is likely higher, as there is woeful underdiagnosis of women and people of color with the disorder. Now that the month is almost over, reflecting on what could have been done better to decrease stigma surrounding the disability is a worthwhile endeavor.

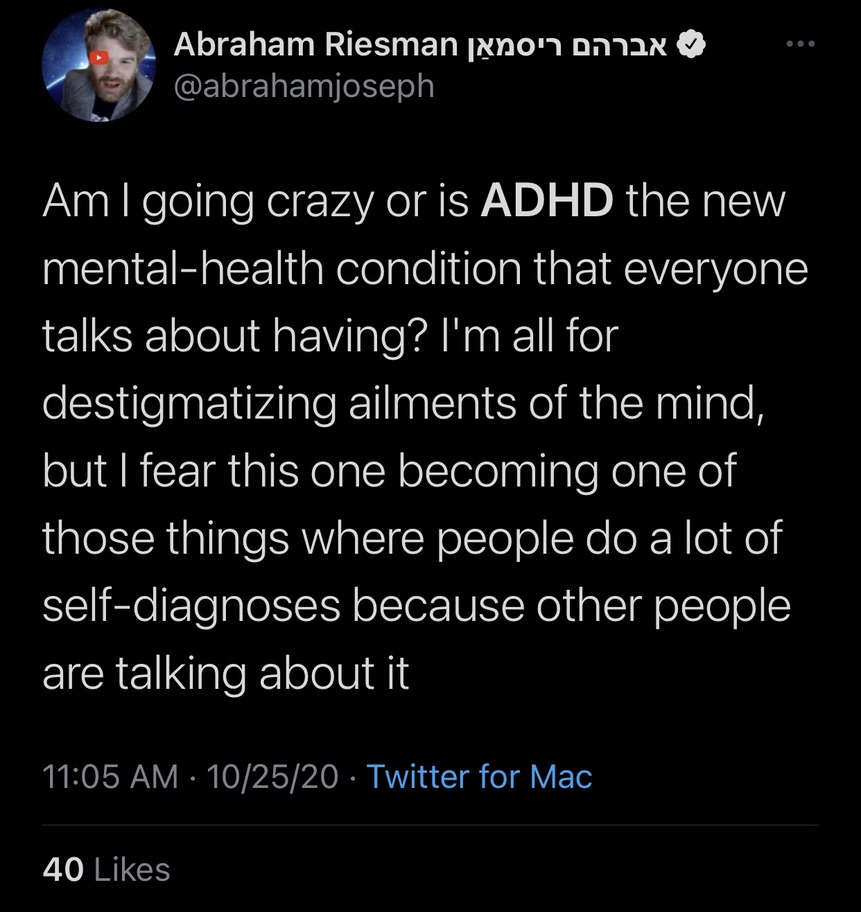

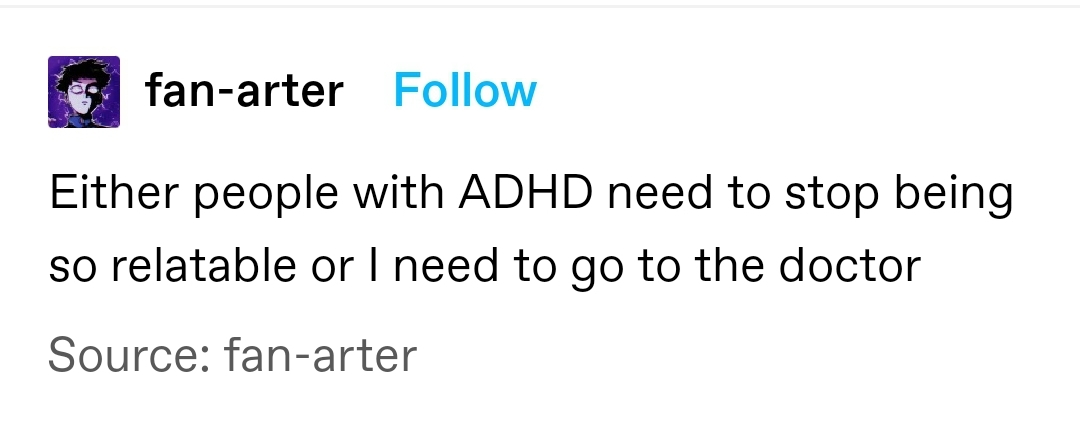

This month, many of those striving to educate the public about ADHD have accidentally simplified the disorder. Vague tweets describe a symptom that could be attributed to a number of disorders or health problems, and this has led to waves of people on social media assuming they have ADHD.

It is always positive for people who have gone undiagnosed to get confirmation about a problem putting a strain on their lives. However, these online portrayals paint a false narrative that ADHD is “relatable.” Traits that could be attributed to anyone with depression, anxiety, OCD, autism, bipolar disorder, PTSD and many different learning disorders are being used exclusively to indicate ADHD.

In reality, ADHD is complicated and genuinely debilitating. I may like parts of my ADHD, such as how it contributes to my creativity. It gives me the ability to hyperfocus on what I enjoy, and it allows me to think in ways the average non-ADHD person would never be able to comprehend. But there are more aspects of the disorder that leave me wishing my mind was neurotypical.

Neurotypical refers to a person who does not have ADHD, autism and/or other neurological disorders that work in similar ways. Someone with one or more of those disorders would be called neurodiverse or neurodivergent. A concept called neurodiversity believes these disorders are part of normal and natural variation in the human genome, not the result of a disease or injury. This is a counter to ableist people who actively search for a “cure” to autism or ADHD when what we really need is help, accommodation and understanding.

Neurodiversity frames these neurological differences as simply that—different, but not inherently bad or deficient. There is evidence that these conditions existed far back into human history. It is even theorized that ADHD played an evolutionary role in benefiting those who lived nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles rather than stationary agrarian ones. Neurodiversity is a way for people with disorders to acknowledge both their benefits and downsides.

People tend to only think about ADHD in terms of attention span and hyperactivity. This is understandable because both are included in the name of the disorder. But this is not the full scope of its symptoms. People with ADHD are unable to regulate their emotions properly. They may get overly irritated by something mundane but inconvenient, and the feeling passes just as soon as it comes. This also results in under-experiencing emotions, such as feeling numb and unable to cry at a funeral of a close relative.

Some believe that ADHD does not actually exist and is made up to prescribe stimulants to children. Or, they believe it is overdiagnosed because “all kids are hyperactive and have attention problems.” This perpetuates harmful stigma and stereotypes and teaches kids to be ashamed of their need to take stimulants to focus. ADHD has been confirmed time and time again to be a real disorder, yet we still have to deal with people denying the reality of our condition. Stimulants have been proven to affect people with ADHD differently than the rest of the population, making us calm and focused instead of over-energized. But no matter how many studies are done, there is always someone trying to claim our disorder is fake.

Possibly the most detrimental belief young people with ADHD are taught is that their tendency to procrastinate or difficulty completing tasks is akin to laziness. But this is far from the truth. Laziness involves an active decision not to do something that can be done easily. With ADHD, you can be trying for days to complete something, but no matter how intense your efforts are, you still can’t get it done. It might be because you can’t concentrate. Sometimes, you suffer from executive dysfunction and can’t switch tasks. Other times, you are so overwhelmed by stress the thought of trying to open a book or laptop causes panic. You lose track of time due to time blindness and realize it’s 5 p.m. and you haven’t eaten, gotten dressed or moved since 8 a.m.

I have the primarily-inattentive type of ADHD (ADHD-PI), and I was only formally diagnosed when I was 20 years old. I was able to get by in elementary and middle school without teachers flagging me as a kid who should get evaluated for a learning disorder. I was relatively quiet, fearful of authority, didn’t have any major behavioral issues and was a voracious reader. But I would constantly daydream and lose focus in class. I would use books as a way to zone out if I found a subject boring. I’d make silly mistakes on homework and exams because I read something too quickly or wasn’t paying close attention. As I continued through school, it became more and more mentally exhausting to try and force myself to concentrate. I would come home and have to lay in a dark room for hours until my brain recharged.

The interests I could sustain attention for were largely academic, so I got the label of “grades too high to be struggling.” An administrator in high school told my parents this verbatim when I tried to get extra time on tests. This denial of 504 accommodations for students with disabilities is against the law, yet sadly a common occurrence.

Once I got to college, my symptoms became harder to navigate around with the increased workload. Years of being undiagnosed put me at a disadvantage. Untreated ADHD in children can lead to an increase in severity of symptoms as a teenager and adult. It results in high occurrences of depression and anxiety disorders in adolescent and teen girls. I am constantly trying to compensate for the lost years when I should have been learning proper skills and coping mechanisms for my disorder. I must play a never-ending game of catch-up just to get to a place where I can manage school, life, work and everything else without having a breakdown every two weeks.

Some of these feelings can be attributed to physical differences in brain structure, development and function. On average, people with ADHD are three years behind in brain development in comparison to their neurotypical counterparts, and certain structures of the brain such as the frontal lobe are smaller than average. A reduction in neurotransmitters for dopamine and norepinephrine leads to reduced brain activity. This can cause people with ADHD to seek activities with instant or short-term rewards in order to increase dopamine, which may outwardly present as impulsivity or risk-taking.

ADHD is not the relatable disorder that many brand it as. ADHD is a disability and has debilitating effects on people’s lives. The incorrect notion that ADHD is not real or people are being over-diagnosed with it is extremely harmful. It perpetuates stigma and stereotypes that cause people like me to fly under the radar and go undiagnosed for years. As this month comes to a close, re-evaluate how you think about ADHD and people with it. None of us benefit from being categorized as one of two extremes.

ADHD is not simply the hyperactive kid who always gets in trouble. ADHD is the girl who is quiet and prone to daydreaming. The kid who gets good grades but still makes mistakes. The one who is trying their hardest but it isn’t quite enough. The teen whose outbursts and mood swings get blamed on bad parenting. The 25-year-old who is still struggling to make it through college. The 40-year-old who feels like they have never been able to get their life together. We’re real people with real struggles. We deserve to have our stories heard and not told by those who think they know everything about our disorder.