DU theatre professor Ashley Hamilton does not have a normal day job. While you can find her teaching Acting 101 to a class of nervous freshmen, you’re more likely to see her hauling costumes and poetry books into various Colorado prisons.

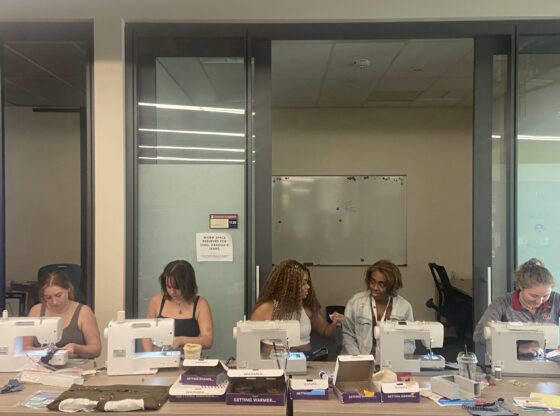

Hamilton is the co-founder and executive director of DU Prison Arts Initiative (DU PAI), an organization that brings arts-based workshops and classes to incarcerated people all across Colorado. Founded in 2017, almost immediately after Hamilton moved from New York City to Denver, DU PAI currently operates in 10 prisons around the state.

Hamilton did not initially envision her life’s work behind penitentiary walls. She received her BFA from CU Boulder in theatre performance and moved to New York City as a bright-eyed Broadway hopeful directly after graduating. After pursuing traditional acting for a couple years, she, “through some different serendipitous events,” found herself going to prisons rather than the stage.

During her time in the Big Apple, Hamilton discovered the “applied arts.” This niche field is a subgroup of fine arts that uses music, theatre, art, creative writing and digital media to create positive change in marginalized communities.

“[I] immediately loved that I could use this thing I had been trained in to create stronger communities and serve communities. I got to explore how communities can transform, change and grow and how to share stories in ways that feel really meaningful,” said Hamilton.

After working specifically in prisons, Hamilton received her PhD in applied theatre and moved to Denver to put her studies on the prison stage.

Hamilton’s work flourished in Colorado and received nationwide fame through features in The New York Times and The Denver Post. She has produced large-scale shows like “A Christmas Carol” (which was on DU’s campus in 2019) and a touring production of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Due to COVID-19, rehearsals for the upcoming rock opera, “Jesus Christ Superstar,” are put on hold at Colorado’s Freemont Prison. DU PAI has also expanded in recent years to include a podcast and a statewide newspaper produced entirely within prisons, by prisoners.

However, Hamilton fears for her students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Colorado prisons house almost 20,000 adult inmates in total, making social distancing measures virtually impossible. This makes incarcerated populations especially vulnerable to disease outbreaks in places where health services are already so limited.

Colorado also has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, with 635 people incarcerated per 100,000 in the state. This is notable compared to the 698 people incarcerated per 100,000 in all of the United States.

COVID-19 may hold serious long-term effects for DU PAI productions due to the amount of incarcerated people who work with the organization; Colorado’s Sterling Prison—the site of DU PAI’s delayed “Antigone” production—had 238 inmates test positive for COVID-19 as of April 22.

“We’re getting really creative and figuring out ways to connect with our students even in this time,” said Hamilton. “Anything we can do to connect with our students, we’re doing.”

Aside from physical ailments, mental health has also proven to be a significant problem for people around the world during the pandemic. For incarcerated people who are already at risk for poor mental health and low social interaction, the pandemic’s repercussions are heightened.

Though she cannot work with her students in person and offer them an outlet for in-person socialization, Hamilton is confident they will find ways to incorporate art into their extreme quarantines.

“I know a lot of the folks we work with have their own artistic practices,” said Hamilton. “They draw, sing and write their own music or poetry. What’s beautiful about art is that it doesn’t go away. You can do it at any time.”

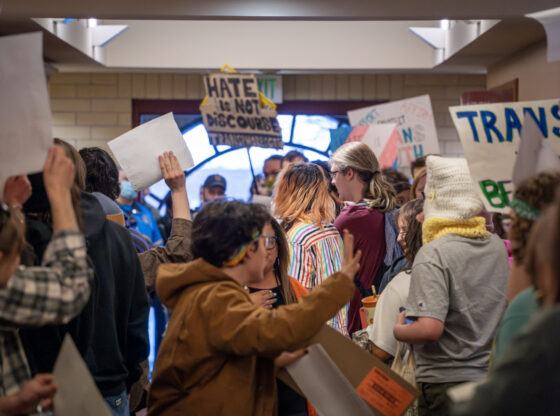

With all the controversy surrounding prison releases and how to handle incarcerated people during the pandemic, the debates surrounding DU PAI are also visible. Hamilton mentioned that people who know about her work are split down the aisle in the constant philosophical battle of rehabilitation vs. punishment. She also stated that questions of “do [inmates] deserve this?” and “are they redeemable?” constantly surface in her work.

“As someone who’s researched this for a really long time, we know that punishment models don’t work,” stated Hamilton. “They actually drive up harm and crime, and they cause people to commit more harm inside the facilities against other incarcerated people and staff. But when people are offered the opportunity to further their education or healing and growth, that is going to majorly shift their behavior.”

Personally, Hamilton has seen her students radically change their behaviors during or after her DU PAI workshops. The students have positively shifted their interpersonal communication, reconnected with family members and friends, stopped doing drugs, revealed new artistic talents and even left gangs.

“I think the arts also make us feel that we are connected to other humans because it’s… something that moves you, said Hamilton. “There’s something about it that I think is really connective.”

Once strict, zero-contact restrictions ease up in Colorado prisons, Hamilton looks forward to resuming her in-person courses and productions put on hold due to the pandemic. She also excitedly awaits continuing publication of the newspaper and podcast. Above all, she simply misses her students.

“Now more than ever, I think that the arts are incredibly important, not just for incarcerated people but for all of us,” said Hamilton. “They allow a space for us to process our emotions, they make us feel connected, and they can be incredibly uplifting and hope-giving.”

Colorado prisons can attest to this, and Colorado communities can all expect much more from Hamilton in the future outside of COVID-19.