The DU While Native project is a five part series, explaining the unique situation Indigenous students are in by attending DU, considering the institution’s history in the Sand Creek Massacre; highlighting the struggles these students face on campus and on their journey through higher education; telling stories of their resistance and survival on campus and more. It serves as a space in which Native students at DU can tell their own stories—stories often shared by many Native students around the country. It serves to educate those outside of the community and give insight to the devastating national statistics about the retention of Indigenous students in higher education. Some students have chosen to use pen names to protect their safety on campus. If you have any questions or comments, please send them to duwhilenative@gmail.com.

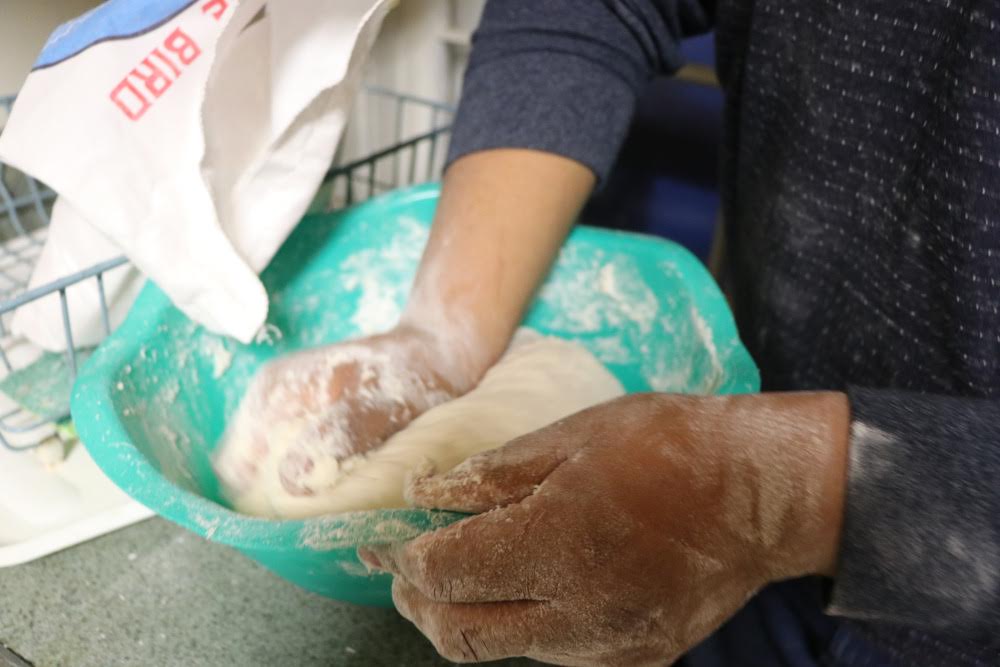

On a cold and snowy Saturday night, on Jan. 16, 2019, five Native students crammed into a small kitchen in a cabin located on Mount Evans. The smell of frybread was thick in the air, as was the smell of freshly cut onions and cooked ground beef. The smells coming from the kitchen indicated that it was Indian Taco night—a type of dinner night familiar to many Native families. However, this particular family isn’t related by blood but considers themselves a family because they are bonded together by being one of the only 35 Native students on DU’s campus.

The Native Student Alliance (NSA) has long called itself a family. Though the group is diverse—coming from different tribes, regions, upbringings etc.—they all relate to having to survive DU as Indigenous students. The group operates on a clan system, of which there are three cohorts: The Elk Clan, or “Hehaka” in Lakota, is made up of the five seniors and our one junior Native student; the Sweet Grass clan is made up of the seven sophomore women students and the Wakiyan cohort, Lakota for “thunder,” are the freshmen students.

Viki Eagle, the director of DU’s Native American Community Partnerships and Programs and the person who mentors and guides NSA, is responsible for naming the cohorts. In a Facebook post from October of 2018, she wrote, “The vision I have always had for our students is that when they speak they are speaking the same words of our ancestors to where the earth shakes to listen and the time stops because words were spoken directly from the heart. I named our cohorts from the fourth year Hehaka (Elks) Cohort to lay the land and find the home within us, the second year Sweetgrass cohort to tie us together. And when the Wakiyan Cohort came in to DU my dream is that they will lead us with a giant thunder bang and flash of lightning on our campus. This is the change we need and will see on our campus. This is my dream.”

Each clan works together to create a community in which Native students can feel welcomed and safe. This community is the foundation for Indigenous students at DU so that they are not only able to survive on campus but are able to resist the injustices and prejudices that they face at the institution.

How Native students survive as a family

The particular Indian Taco night mentioned above took place at the first ever NSA retreat. The retreat was created in order to give Native students a space to debrief after Fall Quarter, as well as look forward to what the group wants NSA to be and to goal-set for the year ahead. For many students, especially for the freshmen students, 2018’s Fall Quarter was challenging and exhausting. After a six-week-long winter break, students were looking for motivation to continue their journey in academia.

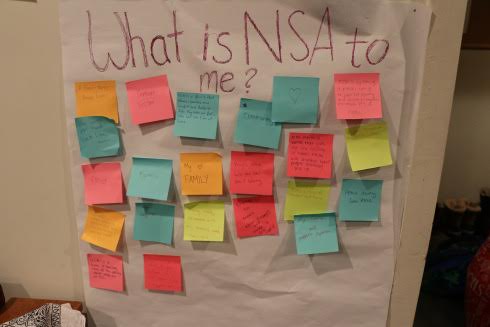

To start the retreat, Viki put up large posters all across the room. Each poster posed a different question, like “What do I want from NSA?,” “What do I want to change about NSA?” and “What is my favorite thing about NSA?” Students were allowed to put sticky notes onto the posters to answer the questions. One poster asked, “What is NSA to me?” Every answer students responded with had to do with family, community and the idea of a home away from home.

The retreat also gave students an opportunity to bond with other Native faculty. Sophia Cisneros, an assistant professor in DU’s Department of Physics & Astronomy, taught the students how to weave baskets, which is a tradition carried by her tribe and many others. While weaving baskets, the students were able to relax and connect in a space of their own that was off DU’s campus—a space only made up of Native people.

Much of the rest of the night included bonding by making dinner, playing card games and sharing the struggles they faced this year in a sharing circle. Students described the experience as a weekend that was needed in order to rejuvenate for the quarter to come.

Salma Ramires Muro described the retreat as “an amazing thing that happened.” She said, “It made me feel closer to my peers, to my found family, and it made me really proud to be a part of NSA.”

NSA has long served as a support system for Native students on DU’s campus. N. Rose said, “NSA here at DU has been a big help to me for staying in school. I feel like my first year was probably the year that, if I was gonna drop out, it was going to be that year, just cause it’s a lot of changes at once. It’s like, you’re a Native person, you’re not on the rez anymore, you’re in a school where the presence of people like you have always been marginalized… so, they’ve [NSA] been there for me. Every single week I would look forward to NSA cause this was a space I could be in that I don’t have to worry about if these people know who or what I am, and they don’t care, regardless of this. And they were facing the same kind of outside pressures that I am, so they understand and I can talk to them about it, and we can all laugh and have fun in a room together for an hour.”

Expressing culture at a PWI

NSA serves as a home away from home for Indigenous students on DU’s campus, and also a place where students are able to express their culture. A lot of times, these cultural practices are kept to themselves, such as participation in cultural ceremonies. But sometimes, the students offer to share aspects of their culture with the greater DU community.

One way that this has been done in the past is by hosting Indigenous fashion shows on campus. In October of 2018, DU and Native Max, a Native-owned fashion and lifestyle magazine based in Denver, teamed up to celebrate both Latinx Heritage Month and Native American Heritage Month by hosting a fashion show that exhibited the cultures of the Indigenous peoples of North and South America.

Another way that this has been done is with DU’s annual New Beginnings Pow Wow. The pow wow began in 2010 to celebrates culture and community, but also to specifically celebrate DU’s graduating students. Every year since, NSA works together to organize the annual event that gets bigger each year. The pow wow draws hundreds of attendees not just from DU, but from tribes across Colorado, New Mexico, Minnesota, South Dakota and Wyoming.

Raelene Woody, as co-chair of NSA, has spent her last three years helping host the pow wow, and describes the event as one of the most meaningful things she has done as a student. “I think the pow wow is the most meaningful time for me as a student, because we get a lot of Native people from the greater Denver area, rather than just DU. I think just having those people dance and having those prayers — having the ground feel those prayers—and having the drums sound at DU and make so much noise and occupying the space makes me feel good, and makes me feel like I belong here at DU.”

Hosting this pow wow gives Native students a sense of pride. Salma said, “[Hosting the pow wow] makes me feel so happy. The first thing I really did when I joined NSA was help out with the pow wow. So, it was my first big event. It was the first thing that really integrated me in a group that I felt at home with.”

The pow wow is seen to Native students as a powerful event—an event in which Indigenous peoples make space for themselves to freely express their cultures in an institution that was not created for them, and that often times, fails them. To Indigenous students, hosting this pow wow is a small form of resistance.

Resisting injustice and prejudice on campus

The annual pow wow is not the only form of resistance in which Native students participate. In the last four years at DU, there have been multiple race-related issues that students of color, including Native students, have protested. In 2016, racially charged messages were written on DU’s free speech wall, so students of color united to send a message to the community that the the incident was unacceptable, then marched to Chancellor Rebecca Chopp’s office to give her their student demands for a safer, more equitable campus. Those same student demands were anonymously altered two weeks later with racially charged language, such as calling Black students “gorillas.” The university never responded to the altering of the student demands. Similarly, in 2018, an anonymous email was sent out to hundreds of students and faculty filled with derogatory remarks about the Latinx community, LGBTQ community, Black community and other marginalized communities.

Native students were a part of these movements and protests, following the lead of the long history in which Indigenous peoples have participated in resistance within the Nation. Founded in 1968, the American Indian Movement (AIM) was a Native-led organization that addressed treaty issues, police brutality and racism against Indigenous peoples. In the following decades, the organization occupied Alcatraz Island, opened up “survival schools” for Native youth who had dropped out of high school, occupied Wounded Knee and more. After AIM, Indigenous activist groups have worked on combating racist mascots, such as the Washington “Redskins,” and have fought to protect the Earth, water and climate, such as with the famous #NoDAPL protests in 2016 fighting the installation of the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota.

In the same year as the #NoDAPL protests, NSA held their own protest on campus in October 2016 for the same reason as the protestors in Standing Rock. That year, DU agreed to host the annual Pipeline Leadership Conference on campus—a conference that included the company responsible for the Dakota Access Pipeline, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP). The protest brought over 300 people, making it one of the largest protests to take place on campus within decades.

“It was really just a slap in the face from DU,” said Raelene. This protest took place during her first quarter, but she took the lead at the protest, as she felt it was deeply connected to what was happening at Standing Rock. She described the moment as both nerve-racking and empowering, “I remember standing up in front of hundreds of people and talking and marching with our allies and Indigenous people who came to DU to help support us and help support the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota.”

In the next few months, DU’s Board of Trustees decided to continue to invest in the fossil fuel industry, to which NSA responded with a letter to the Board about how the fossil fuel industry commits violence against Indigenous communities beyond the destruction of land, and how by investing in these companies, DU is complicit in violence against Native communities, the same communities with whom the university claims to be trying to heal its relationship. Neither the Board or Chancellor Chopp responded to the letter.

Beyond protests and advocacy around racial-related incidents and environmental justice, NSA launched a campaign in 2017 addressing DU’s use of the nickname “Pioneer.” This included NSA making informational pamphlets about DU’s history and why the nickname is problematic, meetings with organizations and administration on campus and hosting events to advocate for a better name.

In March of 2018, DU Student Activists (DUSA) teamed up with NSA to host a “blackout” at DU Hockey’s last home game of the season. At this blackout, the protestors dressed in all black and filled the student section of the hockey game. Every time DU’s team scored, the group held up a banner that said “Pioneers stole Indian land and killed Indian people. #NoMorePios.”

This protest left some students emotionally scarred due to the reaction from the crowd. At the protest, which I was largely responsible for leading, there were adults in the crowd that yelled and heckled us. We were told to “go back to where we came from,” which would be funny to me as a Native student whose ancestors were here long before theirs were, except the fact that we had multiple international and immigrant students in our group. I still remember looking back at a group of white adults who were antagonizing our students from African Students United, all incredibly strong Black women, and looking as they held back their own anger in order to honor our nonviolent action. It was after I saw tears on their faces that I realized, for our own health and safety, we needed to leave. We got up, held hands and left the game together. That night, we made sure no one walked home alone. We were all scared for our safety.

I stayed scared for months after the protest, as alumni started sending threats my way and were creating rumors about our protest. Other NSA students felt similarly. We began to plan carefully about when and where we spoke up against the nickname, making sure we felt safe to do so. At times, we even dropped the campaign until things died down on campus and we felt safe again.

Raelene spoke about the aftermath of the event, “I remember when a couple of articles [about the protest] got published by the DU Clarion, I saw a lot of comments under the thread saying ‘these students should go back to the reservation,’ asking why we are here if we don’t like it, stuff like that that I kind of just laugh at now. There were a couple of articles written that had my full name in it online, and some of the comments said, ‘oh, they should have been genocided.’”

More recently was a round dance/protest hybrid against DU’s “Pioneer” nickname led by our freshmen students. NSA led DU community members through three round dances, traditional dances now performed by many tribes, while passing out stickers labeled things like “#OnStolenLand,” “Pioneering isn’t looking to the future, it’s a reminder of a bloody past” and more. Throughout the event, NSA members educated the greater DU community about issues prominent in the community, such as missing and murdered Indigenous women, loss of language and culture and racist mascots celebrating settler colonialism, such as DU’s nickname. Finally, at the end of the event, the same banner used at the hockey protest was hung from the Hub, DU’s student center, for all of the DU community to see as they passed by.

Many students, especially the first-years, felt empowered by this event.

“Watching that banner drop was super empowering,” said Alexis White Hat. “Just being able to shut people down when they try to be racist or act like they know about Indigenous people [was empowering].”

As well as all the resistance efforts Native students have participated in during their time at DU, some students feel that their existence on campus is a form of resistance in and of itself.

“I think just me existing on campus, just me going to class, just me having a space here and earning my degree is a form of resistance,” Raelene said. “I feel like I resist every day because the founder of DU is culpable in the Sand Creek Massacre and is culpable in policies that were aimed to end Native people. And me being here is a form of resistance because I wasn’t meant to be here.”

Native students advocate for a better future

Though Native students on DU’s campus have had a difficult experience, they still find ways to survive, thrive and resist. The Native Student Alliance provides a space for students to do this, first by providing a family away from home for students, then by empowering students to advocate for themselves and their community.

The reason why Indigenous students on DU’s campus strive to change things on campus is because they truly believe in a better future for DU. The next piece examines steps DU is taking to create a better environment for Native students and what students are still hoping and advocating for in the future.