At the beginning of the school year, Kristen Powell, a Resident Assistant (RA) in Johnson-McFarlane Hall, received an email from one of her residents who would be arriving at DU in a couple of weeks.

In the email, the student explained that they are gender- neutral, meaning they do not identify with a specific gender, preferring to be referenced using pronouns such as “them” and “they.”

Concerned about the provisions for the student in the residence hall, particularly around the bathrooms, Powell spoke to the building’s Resident Director, who told her the process would be “a lot of conversation.”

“What upset me about that response is that we had weeks before the residents came in and we weren’t prepared like we should have been,” said Powell. “To have this resident come in with needs that aren’t being met isn’t fair, particularly when it’s such a major part of your identity, to not be able to express that or participate in the way that you want is really hard.”

As Powell found, bathroom use is one of the most common difficulties faced by transgender students. According to the Transgender Law Center, over 50 percent of gender-variant people report harassment or intimidation in using the bathroom, often because they do not have the gendered appearance of the bathroom they are using or are using the bathroom of a sex they do not identify as.

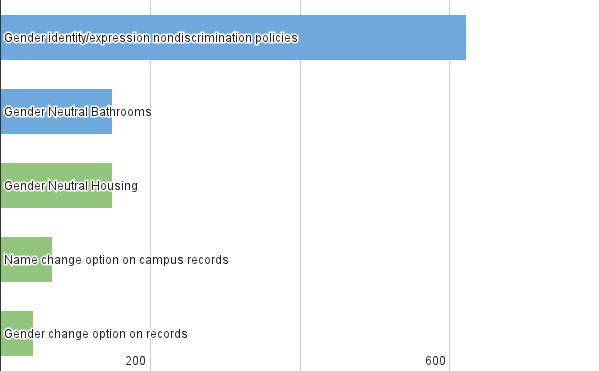

There are now over 150 schools that have gender-neutral bathrooms, according to the Transgender Law Report. While DU has nearly 20 bathrooms open for use by all genders, they can be difficult to find.

“There is a lot of fear around going into a bathroom, especially if you’re not totally dressed as what the other gender dresses as, or have fears about whether or not you can pass successfully or not,” said DU doctorate student Emily Kerr, who runs a male-to-felmale support psychotherapy group. “That breeds a lot of stress and anxiety.”

Each time a transgender person enters a bathroom labeled with a specific gender, DU female to male transgender student Mike says, they face an uncomfortable choice. It is one he’s battled with himself many times.

“You have to choose between affirming your own identity and feeling safe. And I feel like nobody should have to give up feeling safe to validate themselves,” he said.

Campus bathroom use stands as one of the most discussed concerns for transgender students on campuses across the country, and just one of many concerns that create feelings of discomfort for these students. According to the most recent National School Climate Survey, only four percent of transgender students nationwide reported feeling safe at their school.

The students of the Social Justice Living and Learning Community, where Powell is an RA, are still preparing a presentation for the Board of Trustees in effort to turn a bathroom on their floor to gender-netural next year. They have been working on the proposal for over six months.

Recently, there has been more action both on the federal and state level to attempt to address some of these concerns. In April, the Department of Education released guidelines clarifying that transgender students are also protected under Title IX, a federal law protecting against discrimination based on sex in schools. The announcement was received as a major victory for the community, and a mark that there is still work to do. DU is also under investigation by federal authorities for alleged Title IX violations.

Like DU, schools nationwide are beginning to look at barriers within their own policies. There are now more than 623 schools that have non-discrimination policies that address gender identity and expression, including DU.

Last fall, University of North Carolina students marched to demand more gender-neutral housing options, while schools such as the University of Wisconsin at Madison and University of California at Riverside have rolled out new technology allowing students recognition based on their preferred, rather than legal, names.

These are some of the main areas DU’s TransAllies group is targeting as well in their assessment of campus policies. But in assessing the depth of institutional and departmental barriers facing trans-identified students; staff and employees, the group has found the task to be similar to slaying a multi-headed hydra.

“My experience has been that most of the offices and the individuals that we work with on different issues, its more of a lack of knowledge,” said Walker. “And so what we are trying to do is say ‘other schools have done this, we’re not re-inventing the wheel.”

Due to facility restrictions, Walker says, adding all-gender bathrooms to every residence hall may not be possible. However, TransAllies and housing have already begun to look at structural changes involving not only bathrooms, but housing.

Rooming is another issue that brings stress to transgender students, who must live with someone of a different gender, making an uncomfortable situation for both roommates.

This is was a major reason behind Mike’s withdrawing from the university in spring of 2011. When he applied for housing for his sophomore year, he found he would not be allowed to live with his male friends because the university still recognized him by his birth gender of female.

The only other option available to him was to live in a single room in Centennial Towers, sharing a suite with a female.

“That was not a very good option for me,” said Mike. “I didn’t want to feel isolated from all my friends. I felt like I wasn’t allowed to have the college experience that I wanted.”

Struggling in school and frustrated by his lack of options, Mike withdrew and moved to a house near campus, giving himself about a year to work through everything before returning to school.

Across the country, there are 149 colleges that offer gender-neutral housing options for students, according to a running count kept by the Campus Pride Index. DU has no current plans to build housing facilities for gender-variant students, according to Walker, but he hopes to see the university begin to offer inclusive housing options in other ways.

For example, Walker hopes the university will begin to experiment with allowing mixed-gender rooms in university suites, a move he says could benefit more than just transgender students.

“This actually frees up some of the housing stock, because we don’t have a bed sitting empty because we don’t have a member of the correct sex to put there,” said Walker.

Though the issues facing the group are multifaceted, these and numerous concerns highlighted by TransAllies circle back to a single systemic problem: the Banner System, the record-keeping system used on campus.

“As a faculty member, as a student, who you are in Banner defines everything else,” said Walker.

A major step for many transgender students is changing their name to one matching their gender. However, Banner records cannot be altered without matching a student’s Social Security information. Therefore, student IDs, medical records and class rosters will continue to show their birth name and gender. Even when their name is officially changed, altering the student records in the system will erase all the student’s existing data, including financial aid and tax information.

In classrooms, students can be called by names and genders by their professors with which they don’t identify. Former DU graduate, Karen Scarpella, who runs the Gender identity Center for trans-identified people, found while teaching a class last year that she could not use online grading resource Blackboard for this very reason.

“I couldn’t use Blackboard for my class because it was so traumatizing for a student. A few people are aware that this is an issue and have taken a stab at it, but I don’t get a sense that it’s a high priority and that [DU] is really committed to it,” said Scarpella.

It is a difficult situation for many colleges to address. According to the Gender Law report, there are currently 70 colleges out of the approximately 4,000 colleges nationwide that have a process in place for students and staff to change their name on campus records, and 44 that have a process for gender changes.

Mike avoided being called by the wrong name in classes by using the “nickname” section of Blackboard to give the name he now identifies with. He says the importance of finding a way for students to present their preferred name is not only important to validate their identity, but is a matter of safety.

“For a lot of students, it can be really anxiety-causing and sometimes potentially unsafe for that to be revealed as public knowledge,” he said.

Walker acknowledges that altering the system to allow name changes is a potentially difficult and costly process. But he feels it is necessary.

“It’s not a matter of its impossible to change. It could be hard to change, it’s going to take some staff time and those sorts of things,” said Walker. “If we are not going to discriminate, and are in fact going to be inclusive, then as with so many other things we need to put our resources where our words are, and figure it out.”