In the lowest level of the Anderson Academic Commons, almost hidden among the large bookshelves and numerous desks, the DU Collections and Special Archives office is unimposing from the outside. But behind the front desk sit ubiquitous folders, books and papers telling DU’s 150-year story. In its time, DU has seen 16 chancellors (17 by the end of this year), two campuses and visits from three presidents of the United States, all of which is documented in the little office.

As evidenced by the stacks of papers on stocked shelves, DU’s history runs deep. Yet some of the most memorable moments of the school, the most defining and best-remembered events, can be pulled from the piles of information to comprise a story of what are remembered as some of DU’s biggest moments in a long past, those which have instrumentally helped to shape the history of DU, its faculty and its students.

The Founding

When Colorado Governor John Evans founded the University of Denver in 1864, it initially went by the much different title of the Colorado Seminary.

“The thing I always explain to people is that ‘seminary’ in the 1800’s had a little bit different meaning to people than it does today,” said Steve Fisher, university archivist. At the time, according to Fisher, a seminary could also describe institutions of education, but the name was soon changed to be more encompassing.

The university’s campus in downtown Denver

By the mid-1860’s, Denver was struggling through a series of environmental disasters and economic setbacks when the Cherry Creek flooded, destroying parts of downtown Denver, bandits robbed numerous trains passing through the city and a plague of grasshoppers destroyed much of the area vegetation. As Denver’s population dwindled, DU temporarily closed its doors in 1867 with a small student population.

The university did not open again until 13 years later, in 1880, when it became the University of Denver.

“I think they wanted to go with a little bit of a broader term,” said Fisher. “But there is a legal distinction – Colorado Seminary, today, owns all the property, and the land we’re on is the Colorado Seminary’s.”

To this day, university legal documents make note that DU still sits upon Colorado Seminary land by including it in parenthesis next to the words “University of Denver.”

No More Football

Like other Colorado schools at the time, the DU football team was a massive part of DU’s pride and identity through the mid-1900s. But then-chancellor Chester Alter, chancellor from 1953 to 1967 and namesake of the campus arboretum, had some concerns.

“Chester Alter was concerned about what he saw as athlete’s favored status,” said Fisher. “Athletes got better treatment than other students at the time. This was happening all over the country, not just here, but it was happening here. Alter was afraid that we were going to become a jock factory.”

To remedy his fear, Alter did the then-unthinkable act of ending the university football program in 1961. The move was met with minor protesting, Fisher says, but Alter stood by his decision and the university disbanded its football program during its off-season.

“It was quite shocking at the time. It was kind of unexpected, kind of out of nowhere,” said Fisher. “There weren’t rumors flying around or anything like that.”

Hockey came forward to replace the attention the football program received, and life continued on at the university, as Alter had suspected it would.

Fisher said that years later, when Alter was 99, Fisher asked him in an interview if he had regrets about the decision that came to define his term as chancellor.

“I’ll never forget his answer,” said Fisher. “He looked at me and he said ‘Well, we survived didn’t we? We seem to have done alright.’”

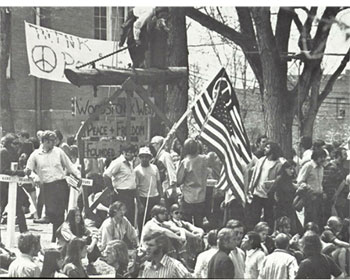

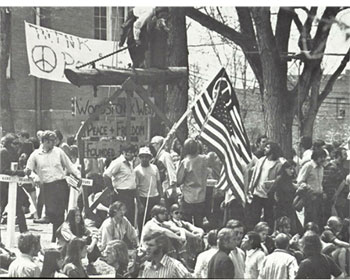

Woodstock West

Always involved, DUs’ campus political activity reached a boiling point in what is dubbed “Woodstock West” in 1970. In the wake of the national turmoil brought by the Kent State shootings and at the apex of demonstrations against the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, 1,500 protesting students erected a tent city on campus on May 6.

Though DU was one of many schools involved in the political fervor of the time, it stands out as one of the few colleges to keep its doors open through much of the protests, according to Fisher.

“Other universities around the country were closing at the time because of student protests, and Mitchell decided that we were going to stay open,” said Fisher. “We were one of the few universities that had a protest movement that actually stayed open.”

Early on, this sentiment resounded with then-Governor John Love, who announced that he would not remove the tent city that had been constructed at the university. A press release sent out by his office noted that the governor was “ready to provide whatever aid and assistance is necessary to the university,” but that police forces would not be used “unless the university specifically requests assistance or there is violence at the university.”

But in the end, the protests would not last. Denver police tore down the commune on May 11, only for students to rebuild it and have it torn down again by the Colorado National Guard on May 13. According to Fisher, Mitchell made the call in order to address anonymous threats coming to the school regarding the commune.

Today, the Anderson Academic Commons stands on the site of the protests, but they continue to a subject of discussion and debate on campus years later.

The Presidential Debate

DU had another marked moment in its history just last year, when the 2012 presidential debate between Republican candidate Mitt Romney and president Barack Obama came to campus. With over 3,000 members of the media on campus, the university was thrust into the national public eye in the days leading up to and during the debate.

Over 5,000 students, staff and community members flooded the Carnegie Green for DebateFest featuring bands, food trucks and a giant big screen to watch the debate. Inside the Ritchie Center, 297 more students were able to see the debate for themselves.

According to a documentary later made by the university about the debate, there were over 100 events leading up to the debate, with a cumulative attendance of over 25,000 people. There were 1,500 ticketed guests for the debate, including 300 students. Outside, 6,000 students and community members attended the Debate Fest. There were 3,000 journalists on campus, including over 700 foreign journalists. The university earned $56 million in advertising revenue.

Presidential Visits

Speaking of presidents, president Obama’s visit to campus for the debate last year was only one among a long history of presidents who have visited campus. DU is quite accustomed to hosting presidential visitors. DU first played host to president William Howard Taft in 1911, followed by a 1950 visit by Dwight Eisenhower, a 1961 visit by Richard Nixon, a visit by future president Ronald Reagan in 1979 and the university even granted Lyndon B. Johnson an honorary degree in 1966. Both presidents Bill Clinton and John F. Kennedy have both had ties with DU, though they never visited campus. Kennedy visited Denver in 1960 for an event sponsored by the DU Social Science Foundation and Clinton participated in the 2008 G8 Summit held in the Phipps Mansion, property then owned by DU.